click photo to enlarge

Concern has been expressed in the press recently about the number, location and quality of the towers that have recently been erected, and are in the pipeline for construction, in London. It's right that there should be a public debate about such things, for at least two reasons. Firstly towers can materially blight a location. Secondly, towers can materially improve a location. The impact of a tower on a settlement, large or small, is greater than almost any other building. Medieval churchmen knew this and constructed theirs with an eye to god and a greater eye to impressing the populace.

In 2006 I touched on this subject in a blog post entitled, "Vertical accents". I briefly revisited it in 2011 in "View with spires". In a post of 2009, "Navigation by church spire", I commented on the usefulness of the church towers and spires as signposts for the cyclist. And, elsewhere in the blog I have spoken of the beauty and pleasure that these structures offer, and the challenges they offer the photographer. Today's photograph show the top of the particularly fine medieval tower of Holy Trinity, Hull, glimpsed above wind-blown tree tops beneath a threatening sky.In the city of Hull this tower continues to be one of the tallest towers in the city. Church towers no longer enjoy that distinction in London. However, careful planning can minimise the negative impact of new tall buildings on these older structures, and I hope that is one of the outcomes of the current debate.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo Title: Tower Top of Holy Trinity, Hull

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 120mm (240mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/1250 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Showing posts with label Hull. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Hull. Show all posts

Friday, September 02, 2016

Wednesday, August 03, 2016

Photographing the horizon

click photo to enlarge

I grew up in a valley on one side of which were, nearby, high, rugged hills and on the other lower hills with a more distant prospect. As a child I called the very tops of the higher side of the valley the "skyline" and summits of the most distant part of lower hills the "horizon". Nobody told me to make this kind of distinction - it simply seemed natural that the skyline was near and clearly above you whereas the horizon was the distant point where earth and sky appear to meet. I still feel that is a reasonable viewpoint.

Perhaps it was growing up in a valley that gave me an interest in the horizon - observing its peculiarities, noting how it changed as I moved, wondering what was beyond it. Quite a few of my photographs feature the horizon (or skyline) and in some, as is the case with today's photograph, most of the detail is clustered there. What I like about scenes and photographs like this one is the way that man's massive achievements - cooling towers, cranes, chimneys, ferries become as nothing when seen against a great river and the vastness of the sky.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo Title: River Humber Seen From Hull Pier

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 42mm (84mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/320 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

I grew up in a valley on one side of which were, nearby, high, rugged hills and on the other lower hills with a more distant prospect. As a child I called the very tops of the higher side of the valley the "skyline" and summits of the most distant part of lower hills the "horizon". Nobody told me to make this kind of distinction - it simply seemed natural that the skyline was near and clearly above you whereas the horizon was the distant point where earth and sky appear to meet. I still feel that is a reasonable viewpoint.

Perhaps it was growing up in a valley that gave me an interest in the horizon - observing its peculiarities, noting how it changed as I moved, wondering what was beyond it. Quite a few of my photographs feature the horizon (or skyline) and in some, as is the case with today's photograph, most of the detail is clustered there. What I like about scenes and photographs like this one is the way that man's massive achievements - cooling towers, cranes, chimneys, ferries become as nothing when seen against a great river and the vastness of the sky.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo Title: River Humber Seen From Hull Pier

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 42mm (84mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/320 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Saturday, July 30, 2016

Improbable photographic colours

click photo to enlarge

Sometimes it's the depth of the blue in the sky, other times its the lurid green of the fresh grass, and frequently it's the improbable reds and oranges of the sunset (or sunrise). The other day, on a visit to the Yorkshire city of Hull (Kingston upon Hull to give it its full title) it was the blackness of the clouds. I'm referring, of course, to the way that reality sometimes looks unreal. In each of the instances cited above the observant viewer or photographer might well think that the saturation slider has been applied with a heavy hand, although there is a school of photography where this kind of embellishment has become pretty much the norm (see 500px.com).

We visited Hull on a day when heavy showers and brighter spells alternated, and the clouds produced by this weather were striking. We were walking near the pier where the River Hull meets the River Humber, passing the end of Queen Street, when we both noticed the smoke-like clouds drifting past the tower of Holy Trinity church. My wife remarked that they wouldn't look real in a photograph and I know just what she means.We have reached a point in the development of digital photography when the manipulation of the relatively faithful images produced by cameras are routinely "enhanced", either straight away and automatically by software (e.g. Google's "auto awesome"), or later by the user's deliberate choice. I really wish it would stop. Our world is awesome enough without making it look otherworldly.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo Title: Queen Street and Holy Trinity, Hull

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 39mm (78mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.3

Shutter Speed: 1/2000 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Sometimes it's the depth of the blue in the sky, other times its the lurid green of the fresh grass, and frequently it's the improbable reds and oranges of the sunset (or sunrise). The other day, on a visit to the Yorkshire city of Hull (Kingston upon Hull to give it its full title) it was the blackness of the clouds. I'm referring, of course, to the way that reality sometimes looks unreal. In each of the instances cited above the observant viewer or photographer might well think that the saturation slider has been applied with a heavy hand, although there is a school of photography where this kind of embellishment has become pretty much the norm (see 500px.com).

We visited Hull on a day when heavy showers and brighter spells alternated, and the clouds produced by this weather were striking. We were walking near the pier where the River Hull meets the River Humber, passing the end of Queen Street, when we both noticed the smoke-like clouds drifting past the tower of Holy Trinity church. My wife remarked that they wouldn't look real in a photograph and I know just what she means.We have reached a point in the development of digital photography when the manipulation of the relatively faithful images produced by cameras are routinely "enhanced", either straight away and automatically by software (e.g. Google's "auto awesome"), or later by the user's deliberate choice. I really wish it would stop. Our world is awesome enough without making it look otherworldly.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo Title: Queen Street and Holy Trinity, Hull

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 39mm (78mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.3

Shutter Speed: 1/2000 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

church,

clouds,

colour saturation,

Holy Trinity,

Hull,

photographic manipulation,

Queen Street,

street

Friday, June 19, 2015

Back street shop front

click photo to enlarge

The British character is traditionally supposed to be low key, reserved, eschewing ostentation and brashness. There is an element of truth in this view. However, there have always been plenty of exceptions to this rule, and the internationalisation of many aspects of life have introduced more "showy" elements into British culture.

When I first crossed the waters that separate our island from the rest of the world one of the first things I noticed was how much more intrusive advertising could be in some European countries. Large cut out letters forming names on top of buildings were commonplace in Greece and France but very rare in Britain. Store fronts often had names on that stretched right across the facade where in Britain they were usually more modest. Roadside adverts were more noticeable even given the lower population density. But, things change, ideas are imported, and Britain now exhibits more of these kinds of features despite having planning regulations that seek to control them. I came across this example in Hull recently. The shop's location off a main thoroughfare clearly prompted the owner to come up with this large, eye-catching advertisement that could be seen by anyone glancing down the side-street. And, despite the colours having begun to fade, it worked, hence my photograph!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 14mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/1000 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

The British character is traditionally supposed to be low key, reserved, eschewing ostentation and brashness. There is an element of truth in this view. However, there have always been plenty of exceptions to this rule, and the internationalisation of many aspects of life have introduced more "showy" elements into British culture.

When I first crossed the waters that separate our island from the rest of the world one of the first things I noticed was how much more intrusive advertising could be in some European countries. Large cut out letters forming names on top of buildings were commonplace in Greece and France but very rare in Britain. Store fronts often had names on that stretched right across the facade where in Britain they were usually more modest. Roadside adverts were more noticeable even given the lower population density. But, things change, ideas are imported, and Britain now exhibits more of these kinds of features despite having planning regulations that seek to control them. I came across this example in Hull recently. The shop's location off a main thoroughfare clearly prompted the owner to come up with this large, eye-catching advertisement that could be seen by anyone glancing down the side-street. And, despite the colours having begun to fade, it worked, hence my photograph!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 14mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/1000 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

advertising,

Britain,

East Yorkshire,

Hull,

shops

Sunday, June 14, 2015

Architecture in black and white

click photo to enlarge

My earliest "serious" photography at the start of the 1970s involved a Russian Zenit E 35mm camera with a 58mm f2 lens and lots of rolls of Ilford FP4 film. It was a fairly basic setup but all that was needed to get an understanding of the basic principles of good exposure and composition. Later I added a couple of lenses, then moved to an Olympus OM-1n, and after a year or two began my own film processing and printing, again, in black and white. At this time colour prints were the favoured means of printing, but I went with black and white and slides (transparencies). At around the time our first child was born I started using colour film.

During those years, and since, architecture has been one of the subjects at which I have most often pointed my camera. Moreover, architecture has been the subject through which I have most frequently reverted to black and white. There's something about the sharp edges and details of buildings, as well as their three-dimensionality, that makes them ideal subjects for presenting in monochrome. Today's photograph is of the Wilberforce Health Centre, Hull, a 2011 building by HLM Architects. The colours of the building are off-white and grey with highlights of dark red, quite eye-catching. However, the contrasts of the colours alongside the shadows produced by a bright June day suggested to me that the building might look well with a black and white treatment. I think it does, especially with the digital equivalent of a yellow filter that darkens the sky and gives the building greater emphasis.

Incidentally, you may wonder what has happened to the rightmost cyclist's bicycle - it appears to be missing a wheel. In fact it's a small-wheel folding bike produced by the British manufacturer, Brompton and it's yet to be unfolded.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 9mm (18mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6 Shutter Speed: 1/1600 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

My earliest "serious" photography at the start of the 1970s involved a Russian Zenit E 35mm camera with a 58mm f2 lens and lots of rolls of Ilford FP4 film. It was a fairly basic setup but all that was needed to get an understanding of the basic principles of good exposure and composition. Later I added a couple of lenses, then moved to an Olympus OM-1n, and after a year or two began my own film processing and printing, again, in black and white. At this time colour prints were the favoured means of printing, but I went with black and white and slides (transparencies). At around the time our first child was born I started using colour film.

During those years, and since, architecture has been one of the subjects at which I have most often pointed my camera. Moreover, architecture has been the subject through which I have most frequently reverted to black and white. There's something about the sharp edges and details of buildings, as well as their three-dimensionality, that makes them ideal subjects for presenting in monochrome. Today's photograph is of the Wilberforce Health Centre, Hull, a 2011 building by HLM Architects. The colours of the building are off-white and grey with highlights of dark red, quite eye-catching. However, the contrasts of the colours alongside the shadows produced by a bright June day suggested to me that the building might look well with a black and white treatment. I think it does, especially with the digital equivalent of a yellow filter that darkens the sky and gives the building greater emphasis.

Incidentally, you may wonder what has happened to the rightmost cyclist's bicycle - it appears to be missing a wheel. In fact it's a small-wheel folding bike produced by the British manufacturer, Brompton and it's yet to be unfolded.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 9mm (18mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6 Shutter Speed: 1/1600 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, June 12, 2015

Return to Prince Street, Hull

click photo to enlarge

Like many photographers, when I find a subject that appeals to me I try to secure the best photograph of it that I possibly can. However, if you have only a single occasion on which to get your shot, then you have to put up with the light, weather, season and other circumstances that prevail at the time. Consequently the end result can be disappointing because you don't achieve the possibilities that you can see in the subject.

But, where the subject is one that you can photograph with reasonable frequency the opportunity exists to improve on your earlier efforts. If you look through this blog you will find several photographs where this has been my motivation. The Humber Bridge is one such example in this blog - see here for the deep rich colours of winter, here for a dull, damp winter view, and here for a contre jour shot with people for scale. Today's post is another example of a trying to get a better shot of a subject.

I first photographed Prince Street in Hull in the 1970s and 1980s. The view from the Market Place through the archway to the curving line of three-storey, multicoloured, terraced houses of the 1770s is quite appealing. I'd more recently tried again with the subject at the end of November 2012. On that last occasion the flat lighting and the line of rubbish bins waiting to be emptied detracted from the shot. The weather on our recent visit was much more promising, and as we walked through this part of the Old Town I tried again and produced a shot that I like much better. The contrast between the deep shadows of the arch and trees with the bright, sunlit buildings works very nicely, and the silhouette of the wall-mounted street light adds a welcome detail.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 28mm (56mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6 Shutter Speed: 1/2000 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Like many photographers, when I find a subject that appeals to me I try to secure the best photograph of it that I possibly can. However, if you have only a single occasion on which to get your shot, then you have to put up with the light, weather, season and other circumstances that prevail at the time. Consequently the end result can be disappointing because you don't achieve the possibilities that you can see in the subject.

But, where the subject is one that you can photograph with reasonable frequency the opportunity exists to improve on your earlier efforts. If you look through this blog you will find several photographs where this has been my motivation. The Humber Bridge is one such example in this blog - see here for the deep rich colours of winter, here for a dull, damp winter view, and here for a contre jour shot with people for scale. Today's post is another example of a trying to get a better shot of a subject.

I first photographed Prince Street in Hull in the 1970s and 1980s. The view from the Market Place through the archway to the curving line of three-storey, multicoloured, terraced houses of the 1770s is quite appealing. I'd more recently tried again with the subject at the end of November 2012. On that last occasion the flat lighting and the line of rubbish bins waiting to be emptied detracted from the shot. The weather on our recent visit was much more promising, and as we walked through this part of the Old Town I tried again and produced a shot that I like much better. The contrast between the deep shadows of the arch and trees with the bright, sunlit buildings works very nicely, and the silhouette of the wall-mounted street light adds a welcome detail.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 28mm (56mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6 Shutter Speed: 1/2000 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

arch,

cobblestones,

East Yorkshire,

eighteenth century,

Hull,

Prince street,

terrace

Wednesday, June 10, 2015

Art Deco shops

click photo to enlarge

I've written elsewhere in this blog about how, in Britain, the architecture of the 1920s and 1930s was very conservative, noting but not, in the main embracing, the forward-looking developments of Europe and the United States.

This often manifested itself in a style that is sometimes called "stripped classical" with recognisably Greek, Roman or Renaissance-derived columns, entablatures etc pared down to plainer, un-archaeological forms; a reluctant nod to Modernism. The style known as Art Deco and its synonyms or variants, Moderne and Jazz Moderne and Streamline Modern, also used classical forms in this way, but more enthusiastically and with the introduction of newer and different elements. British cinemas of the 1930s frequently adopted this style, as did quite a few factories and even power stations. On the high street Marks and Spencer's architects used white stone with classical, streamline and even Central American motifs in an attempt to show their modernity. The men's clothing store that was found in most large towns and cities - Burton - also adopted this approach.

On our recent visit to Hull I photographed the main windows of the curved facade of the Burton store at the top of Whitefriargate. This building dates from 1935 and is the work of the store's architect, Harry Wilson. It is faced in a veneer of black marble slabs with tall, narrow window bands featuring attenuated glazing bars. The central windows are given a "classical" emphasis with a pair of pilasters. However, the capitals are, if we are to compare them with anything, stripped down Egyptian! The balconies have iron-work featuring curved bars, not unlike those on the step ventilators of the Art Deco doorway of Hull railway station's hotel. The colour of the paintwork is gold, making the building stand out even more from its much more staid neighbours.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 23mm (46mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6 Shutter Speed: 1/500 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

I've written elsewhere in this blog about how, in Britain, the architecture of the 1920s and 1930s was very conservative, noting but not, in the main embracing, the forward-looking developments of Europe and the United States.

This often manifested itself in a style that is sometimes called "stripped classical" with recognisably Greek, Roman or Renaissance-derived columns, entablatures etc pared down to plainer, un-archaeological forms; a reluctant nod to Modernism. The style known as Art Deco and its synonyms or variants, Moderne and Jazz Moderne and Streamline Modern, also used classical forms in this way, but more enthusiastically and with the introduction of newer and different elements. British cinemas of the 1930s frequently adopted this style, as did quite a few factories and even power stations. On the high street Marks and Spencer's architects used white stone with classical, streamline and even Central American motifs in an attempt to show their modernity. The men's clothing store that was found in most large towns and cities - Burton - also adopted this approach.

On our recent visit to Hull I photographed the main windows of the curved facade of the Burton store at the top of Whitefriargate. This building dates from 1935 and is the work of the store's architect, Harry Wilson. It is faced in a veneer of black marble slabs with tall, narrow window bands featuring attenuated glazing bars. The central windows are given a "classical" emphasis with a pair of pilasters. However, the capitals are, if we are to compare them with anything, stripped down Egyptian! The balconies have iron-work featuring curved bars, not unlike those on the step ventilators of the Art Deco doorway of Hull railway station's hotel. The colour of the paintwork is gold, making the building stand out even more from its much more staid neighbours.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 23mm (46mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6 Shutter Speed: 1/500 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Monday, June 08, 2015

Hull, UK City of Culture 2017

click photo to enlarge

For part of the 1970s and 1980s I lived in the city of Hull, or to give it its Sunday name, Kingston upon Hull. Before I went to there I knew little about the place other than that it was a large, Yorkshire port on the east coast of England. What I discovered was that it is a fascinating place with a long and interesting history, an appearance that is substantially different from many English cities. I also came to understand that it has a bad press from people who have never been there and only know of it from reading the opinions of other people who have never been there for more than a day.

Consequently, when it was first announced that Hull was to be the UK's 2017 "City of Culture" I thought, "Good, it has plenty of culture and can wear the accolade well." Of course, no amount of exposure to its galleries, theatres, concert venues, architecture, etc will overcome the opinion of some who will continue to know the city through the saying, "From Hull, Hell and Halifax, Lord deliver us", and through its passion for sport, particularly rugby league. When I moved to Hull it was rugby league that dominated, and despite the town's soccer team ascending to the Premiership (and being relegated from it this year), that remains the case.

Today's photograph risks confirming that stereoype because its focal point is someone in a Hull Kingston Rovers rugby league shirt. Incidentally Hull KR are the rugby team of east Hull, and Hull FC the equivalent of west Hull. Here the wearer of this welcome bright red note for my photograph is returning with his companion from west to east. They are ascending the new Scale Lane swing footbridge over the River Hull, the waterway that bisects the city from north to south and separates east from west.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 28mm (17mm - 34mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6 Shutter Speed: 1/2000 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

For part of the 1970s and 1980s I lived in the city of Hull, or to give it its Sunday name, Kingston upon Hull. Before I went to there I knew little about the place other than that it was a large, Yorkshire port on the east coast of England. What I discovered was that it is a fascinating place with a long and interesting history, an appearance that is substantially different from many English cities. I also came to understand that it has a bad press from people who have never been there and only know of it from reading the opinions of other people who have never been there for more than a day.

Consequently, when it was first announced that Hull was to be the UK's 2017 "City of Culture" I thought, "Good, it has plenty of culture and can wear the accolade well." Of course, no amount of exposure to its galleries, theatres, concert venues, architecture, etc will overcome the opinion of some who will continue to know the city through the saying, "From Hull, Hell and Halifax, Lord deliver us", and through its passion for sport, particularly rugby league. When I moved to Hull it was rugby league that dominated, and despite the town's soccer team ascending to the Premiership (and being relegated from it this year), that remains the case.

Today's photograph risks confirming that stereoype because its focal point is someone in a Hull Kingston Rovers rugby league shirt. Incidentally Hull KR are the rugby team of east Hull, and Hull FC the equivalent of west Hull. Here the wearer of this welcome bright red note for my photograph is returning with his companion from west to east. They are ascending the new Scale Lane swing footbridge over the River Hull, the waterway that bisects the city from north to south and separates east from west.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Olympus E-M10

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 28mm (17mm - 34mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6 Shutter Speed: 1/2000 sec

ISO:200

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Tuesday, May 12, 2015

Art Deco doorway

click photo to enlarge

English architecture of the 1930s was relatively unadventurous compared with that which was being built in continental Europe and the United States. The only buildings that can stand with the modernist structures across the water were built either by emigres fleeing the turmoil of pre-war Europe e.g. , the De La Warr Pavilion of Erich Mendelsshon and Serge Chermayeff, or by the small group of British architects e.g.Wells Coates, Maxwell Fry and Owen Williams, who were influenced by their continental and U.S. colleagues. The majority of English architects in the 1930s built very traditionally and acknowledged modern trends mainly by the application of decorative elements such as metal window frames with horizontal glazing bars, inappropriate flat roofs, or "Moderne" features using stripped down decorative elements, often drawn from classical precedents. A very few architects embraced the decorative tics of Art Deco, a style that had more success in the decorative arts than in architecture.

The other day, on one of our visits to Hull, we visited the Paragon railway station hotel (now the Royal Hotel, formerly the Royal Station Hotel), a fine stone building of 1849 by the architect G. T. Andrews. This is one of the few central Hull buildings that largely escaped the devastating bombing that the city suffered in WW2. A serious fire in 1990 saw careful rebuilding and consequently today we can admire its composition, carving and imposing facade. We can also enjoy the Art Deco doorway that was added to the entrance from the station concourse in the 1930s. This very theatrical entry has a rounded arch that echoes those of the older building. However, it is simplified, involves white glass illuminated from inside, and has decorative "curls" at the bottom. A glazed "overdoor" is also in very simply composed stained glass. The classical setting is acknowledged by the royal coat of arms that surmounts the doorway, and by the discreet brackets at the top left and right. Decorative metalwork can be seen in the ventilators in the centre of the steps. The whole composition feels like something lifted out of a 1930s cinema, or an American city, and in this context inserts a welcome note of gaiety that all too few people seem to notice.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 48mm (72mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/80 sec

ISO:125 Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

English architecture of the 1930s was relatively unadventurous compared with that which was being built in continental Europe and the United States. The only buildings that can stand with the modernist structures across the water were built either by emigres fleeing the turmoil of pre-war Europe e.g. , the De La Warr Pavilion of Erich Mendelsshon and Serge Chermayeff, or by the small group of British architects e.g.Wells Coates, Maxwell Fry and Owen Williams, who were influenced by their continental and U.S. colleagues. The majority of English architects in the 1930s built very traditionally and acknowledged modern trends mainly by the application of decorative elements such as metal window frames with horizontal glazing bars, inappropriate flat roofs, or "Moderne" features using stripped down decorative elements, often drawn from classical precedents. A very few architects embraced the decorative tics of Art Deco, a style that had more success in the decorative arts than in architecture.

The other day, on one of our visits to Hull, we visited the Paragon railway station hotel (now the Royal Hotel, formerly the Royal Station Hotel), a fine stone building of 1849 by the architect G. T. Andrews. This is one of the few central Hull buildings that largely escaped the devastating bombing that the city suffered in WW2. A serious fire in 1990 saw careful rebuilding and consequently today we can admire its composition, carving and imposing facade. We can also enjoy the Art Deco doorway that was added to the entrance from the station concourse in the 1930s. This very theatrical entry has a rounded arch that echoes those of the older building. However, it is simplified, involves white glass illuminated from inside, and has decorative "curls" at the bottom. A glazed "overdoor" is also in very simply composed stained glass. The classical setting is acknowledged by the royal coat of arms that surmounts the doorway, and by the discreet brackets at the top left and right. Decorative metalwork can be seen in the ventilators in the centre of the steps. The whole composition feels like something lifted out of a 1930s cinema, or an American city, and in this context inserts a welcome note of gaiety that all too few people seem to notice.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 48mm (72mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/80 sec

ISO:125 Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

architecture,

Art Deco,

doorway,

Hull,

Royal Hotel,

station

Wednesday, May 06, 2015

The Albemarle Music Centre, Hull

click photo to enlarge

Sandwiched between the prominent St Stephen Centre shopping area and the Hull Truck Theatre Company building, and forming part of the regeneration of this part of Hull, is the Albemarle Music Centre. This striking building, erected in 2007, is the music hub for the city's school children. It provides a base for the specialist staff who teach music across Hull's schools as well as practice and performance spaces for young musicians and visiting music groups. Part of the building is a 164 seat auditorium that can accommodate a full symphony orchestra. This space can seat a further 80 when smaller ensembles perform. The large (purple) cone shape forms part of this concert hall.

The building is the work of Holder Mathias Architects, a firm with a wide practice that includes the neighbouring shopping centre. The Albermarle Music Centre is a nice contrast with the adjoining sites and, through the prominent rounded shape, tips its hat, it seems to me, to Le Corbusier. The only aspect of the project that concerns me is the material of the dark purple cone-like shape. It is rough textured and already has a green growth in the shady areas. It will require regular cleaning and maintenance.

When I took my photograph I had thought that the colour of the cone would be the feature I'd highlight. However, black and white, to my mind, is a treatment that often suits architecture. In this instance I liked the way it describes the form of the building so I chose it over my initial preference.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 18mm (27mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/320 sec

ISO:100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Sandwiched between the prominent St Stephen Centre shopping area and the Hull Truck Theatre Company building, and forming part of the regeneration of this part of Hull, is the Albemarle Music Centre. This striking building, erected in 2007, is the music hub for the city's school children. It provides a base for the specialist staff who teach music across Hull's schools as well as practice and performance spaces for young musicians and visiting music groups. Part of the building is a 164 seat auditorium that can accommodate a full symphony orchestra. This space can seat a further 80 when smaller ensembles perform. The large (purple) cone shape forms part of this concert hall.

The building is the work of Holder Mathias Architects, a firm with a wide practice that includes the neighbouring shopping centre. The Albermarle Music Centre is a nice contrast with the adjoining sites and, through the prominent rounded shape, tips its hat, it seems to me, to Le Corbusier. The only aspect of the project that concerns me is the material of the dark purple cone-like shape. It is rough textured and already has a green growth in the shady areas. It will require regular cleaning and maintenance.

When I took my photograph I had thought that the colour of the cone would be the feature I'd highlight. However, black and white, to my mind, is a treatment that often suits architecture. In this instance I liked the way it describes the form of the building so I chose it over my initial preference.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 18mm (27mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/320 sec

ISO:100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

Albemarle Music Centre,

architecture,

black and white,

Hull,

modern,

Yorkshire

Saturday, May 02, 2015

Old cinema architecture

click photo to enlarge

The design of the first railway carriages were closely modelled on that of the horse-drawn carriage. This seemed entirely right at the time. After all, wasn't there a similarity of function between a carriage pulled by an engine and one pulled by a horse?

When architects and builders began to erect the first purpose-built cinemas a similar mind-set seems to have taken hold. Cinemas were places of mass entertainment that held a large audience of people who all looked at the same spectacle in front of them. This was very much like the music-halls, theatres and concert halls of the time. Consequently it seemed entirely reasonable to draw upon their designs and decoration when building the new venues of mass-entertainment. To look at the music-hall architecture of someone like Frank Matcham and then at the cinemas of the first two decades of the twentieth century is to see many similarities. It is true that the sum spent on the average cinema's architecture was often less than on a music hall. However, the same debased classical features and the borrowings from exotic architectural styles (Moorish and Oriental were popular) pervade most such buildings.

The other day I stood in front of the former Tower Cinema in Hull. This was built by a Hull architect, H. Percival Binks, in 1914. The overall style is classical with domes, obelisk pinnacles, pediments, pilasters, rustication, swags, even a pseudo Diocletian window and an allegorical figure. However, it is faced in the then fashionable green and cream faience and has debased Art Nouveau touches - see particularly the stained glass lettering and its surrounding low arch. When built it must have seemed very up-to-date and quite different from the staid stone and brick of the Victorian buildings of the city; in fact, perfectly in keeping with the technological marvel of the moving pictures on display inside. Today it is no longer a cinema but some sort of night club. Mercifully, with the exception of a band of grey paint over the lower level tiles, little has been changed on the facade and so it remains an interesting building that speaks of its time of construction.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 18mm (27mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/200 sec

ISO:100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

The design of the first railway carriages were closely modelled on that of the horse-drawn carriage. This seemed entirely right at the time. After all, wasn't there a similarity of function between a carriage pulled by an engine and one pulled by a horse?

When architects and builders began to erect the first purpose-built cinemas a similar mind-set seems to have taken hold. Cinemas were places of mass entertainment that held a large audience of people who all looked at the same spectacle in front of them. This was very much like the music-halls, theatres and concert halls of the time. Consequently it seemed entirely reasonable to draw upon their designs and decoration when building the new venues of mass-entertainment. To look at the music-hall architecture of someone like Frank Matcham and then at the cinemas of the first two decades of the twentieth century is to see many similarities. It is true that the sum spent on the average cinema's architecture was often less than on a music hall. However, the same debased classical features and the borrowings from exotic architectural styles (Moorish and Oriental were popular) pervade most such buildings.

The other day I stood in front of the former Tower Cinema in Hull. This was built by a Hull architect, H. Percival Binks, in 1914. The overall style is classical with domes, obelisk pinnacles, pediments, pilasters, rustication, swags, even a pseudo Diocletian window and an allegorical figure. However, it is faced in the then fashionable green and cream faience and has debased Art Nouveau touches - see particularly the stained glass lettering and its surrounding low arch. When built it must have seemed very up-to-date and quite different from the staid stone and brick of the Victorian buildings of the city; in fact, perfectly in keeping with the technological marvel of the moving pictures on display inside. Today it is no longer a cinema but some sort of night club. Mercifully, with the exception of a band of grey paint over the lower level tiles, little has been changed on the facade and so it remains an interesting building that speaks of its time of construction.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 18mm (27mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/200 sec

ISO:100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

architecture,

cinema,

design,

Hull,

Tower Cinema,

Yorkshire

Tuesday, February 17, 2015

Church clock mechanisms

click photo to enlarge

I'm not someone who is particularly interested in mechanical objects. I maintain my bicycle quite well and don't mind doing so. But, I bought a car on the understanding that I wouldn't have to poke about in the engine. That indifference to things mechanical spreads to most other areas including old clocks. There are those who relish looking at and tinkering with the innards of clocks. Whilst I understand, I think, their motivation and fascination, I don't share it.

During my wanderings around churches I frequently come across the mechanical workings of tower clocks. Sometimes these are old, no longer used clocks, often dating from the late medieval or Georgian period, put on display in an aisle or a transept, gathering dust and tick-tocking no more. Other times I climb towers and pass by the current mechanism driving hands that can be five feet long on a face twelve feet or more across. That happened a while ago when we went up the tower of Holy Trinity in Kingston upon Hull. The workings, as can be seen in today's photograph, date from 1903 and came from the Leeds clockmakers, W. Potts & Son Ltd. Everything looked beautifully kept, well oiled, with nicely painted wood and metal, and shiny, polished brass; perfect for a photograph.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 24mm (36mm - 35mm equiv.) - cropped to 4:3 ratio

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/40 sec

ISO:900

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

I'm not someone who is particularly interested in mechanical objects. I maintain my bicycle quite well and don't mind doing so. But, I bought a car on the understanding that I wouldn't have to poke about in the engine. That indifference to things mechanical spreads to most other areas including old clocks. There are those who relish looking at and tinkering with the innards of clocks. Whilst I understand, I think, their motivation and fascination, I don't share it.

During my wanderings around churches I frequently come across the mechanical workings of tower clocks. Sometimes these are old, no longer used clocks, often dating from the late medieval or Georgian period, put on display in an aisle or a transept, gathering dust and tick-tocking no more. Other times I climb towers and pass by the current mechanism driving hands that can be five feet long on a face twelve feet or more across. That happened a while ago when we went up the tower of Holy Trinity in Kingston upon Hull. The workings, as can be seen in today's photograph, date from 1903 and came from the Leeds clockmakers, W. Potts & Son Ltd. Everything looked beautifully kept, well oiled, with nicely painted wood and metal, and shiny, polished brass; perfect for a photograph.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 24mm (36mm - 35mm equiv.) - cropped to 4:3 ratio

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/40 sec

ISO:900

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, February 13, 2015

Paragon Arcade, Hull

click photo to enlarge

Whenever I express my enthusiasm for the Victorian shopping arcade I find someone voicing their agreement. There's something about the shelter, light, architecture, ornament, cosiness, and atmosphere of them that appeals to people. Not all people, however. Quite a few traders find the shop spaces too small for their needs and it's a fact that only certain kinds of businesses can flourish in these old arcades. Often it is smaller, independent, niche retailers. Clothes, musical instruments, confectionery, jewellery, books, hair-dressing and cafes are typical of the goods and services to be found in them. Of course, Victorian arcades tend to be found in the centres of cities so rents are relatively high and consequently retailers have to generate good sales to afford the small premises. Perhaps it's this that results in what appears, to my eyes at least, the higher than normal turnover of businesses in them. That's not to say that some don't flourish for decades: I can think of one arcade that has had the same joke shop and hi-fi retailer for at least the past forty years.

The Paragon Arcade in Hull city centre has a short and straight configuration - many are curved or have a right angle turn or a transeptal arrangement. It was built in 1892 by W.A. (later Sir Alfred) Gelder, a prominent Hull architect and politician who became Lord Mayor, and after whom one of the city's main streets is named. It is in the Venetian Gothic style and retains much of its original character. But, like most shops, the upper storeys are least altered and in this case the glazed roof is intact too. The glass is supported by highly ornate arches of cast iron.

The Paragon Arcade is a good, but not outstanding example of the type. It is modest, unlike the massive splendour of London's Leadenhall Market. Its ornament, though fine, cannot compete with that of The Royal Arcade, Norwich. And its glazing doesn't have the railway station scale of Southport's Leyland Arcade. But, its relatively modest scale notwithstanding, it is an ornament in the centre of the city where it stands.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 60mm (90mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/100 sec

ISO:280

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Whenever I express my enthusiasm for the Victorian shopping arcade I find someone voicing their agreement. There's something about the shelter, light, architecture, ornament, cosiness, and atmosphere of them that appeals to people. Not all people, however. Quite a few traders find the shop spaces too small for their needs and it's a fact that only certain kinds of businesses can flourish in these old arcades. Often it is smaller, independent, niche retailers. Clothes, musical instruments, confectionery, jewellery, books, hair-dressing and cafes are typical of the goods and services to be found in them. Of course, Victorian arcades tend to be found in the centres of cities so rents are relatively high and consequently retailers have to generate good sales to afford the small premises. Perhaps it's this that results in what appears, to my eyes at least, the higher than normal turnover of businesses in them. That's not to say that some don't flourish for decades: I can think of one arcade that has had the same joke shop and hi-fi retailer for at least the past forty years.

The Paragon Arcade in Hull city centre has a short and straight configuration - many are curved or have a right angle turn or a transeptal arrangement. It was built in 1892 by W.A. (later Sir Alfred) Gelder, a prominent Hull architect and politician who became Lord Mayor, and after whom one of the city's main streets is named. It is in the Venetian Gothic style and retains much of its original character. But, like most shops, the upper storeys are least altered and in this case the glazed roof is intact too. The glass is supported by highly ornate arches of cast iron.

The Paragon Arcade is a good, but not outstanding example of the type. It is modest, unlike the massive splendour of London's Leadenhall Market. Its ornament, though fine, cannot compete with that of The Royal Arcade, Norwich. And its glazing doesn't have the railway station scale of Southport's Leyland Arcade. But, its relatively modest scale notwithstanding, it is an ornament in the centre of the city where it stands.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 60mm (90mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/100 sec

ISO:280

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

Hull,

ironwork,

Paragon,

shopping arcade,

Venetian Gothic,

Victorian

Thursday, February 05, 2015

Holy Trinity, Hull

click photo to enlarge

Holy Trinity, Hull, is one of those medieval churches that should be much better known. Its absence from lists of renowned churches is probably due to its location in a city that, for people south of Watford, is imagined to to be a depressed northern backwater. In fact, it sits near the ancient heart of an old settlement, one that had and continues to have national importance, and which still retains many fine historic buildings in a very distinctive and different kind of urban setting. The church of Holy Trinity would grace any city, and were it in the home counties, would be feted and a major visitor attraction.

So, what does the building, erected between 1285 and the mid-1500s, offer. Firstly it is big (length 285ft/87m, width 72ft/22m, height 150ft/46m), often described as the biggest English parish church by area, bigger in fact than some small cathedrals. The size gives grandeur and awe to the interior, and the painted ceilings are spectacular. Then there is the transept walls and the lower stage of the crossing tower. These were built of brick in the 1300s, a very early use of this material in the medieval period, and said to be the first use of brick for a large building in Britain since the time of the Romans. The tower itself is a particularly fine example of the Perpendicular style and still able to hold its own against more recent tall buildings in the city. Finally there is the west front that overlooks the Market Place. It too is an exceptional piece of work, well-proportioned, symmetrical with good window tracery and a lovely entrance doorway. It has to be said that the setting of the church adds to its appeal. Around it are narrow streets, the old Market Place, the newer (1902-4) Market Hall, the old Grammar School (also brick, 1583-5), Trinity House, and a host of Victorian and earlier buildings.

The January day on which I took my photograph was cold and bright. I liked the way Holy Trinity's tower and the upper parts of the nave, transepts and chancel appeared to rise towards the light out of the deep shadows of the surrounding streets.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 18mm (27mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/125 sec

ISO:100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Holy Trinity, Hull, is one of those medieval churches that should be much better known. Its absence from lists of renowned churches is probably due to its location in a city that, for people south of Watford, is imagined to to be a depressed northern backwater. In fact, it sits near the ancient heart of an old settlement, one that had and continues to have national importance, and which still retains many fine historic buildings in a very distinctive and different kind of urban setting. The church of Holy Trinity would grace any city, and were it in the home counties, would be feted and a major visitor attraction.

So, what does the building, erected between 1285 and the mid-1500s, offer. Firstly it is big (length 285ft/87m, width 72ft/22m, height 150ft/46m), often described as the biggest English parish church by area, bigger in fact than some small cathedrals. The size gives grandeur and awe to the interior, and the painted ceilings are spectacular. Then there is the transept walls and the lower stage of the crossing tower. These were built of brick in the 1300s, a very early use of this material in the medieval period, and said to be the first use of brick for a large building in Britain since the time of the Romans. The tower itself is a particularly fine example of the Perpendicular style and still able to hold its own against more recent tall buildings in the city. Finally there is the west front that overlooks the Market Place. It too is an exceptional piece of work, well-proportioned, symmetrical with good window tracery and a lovely entrance doorway. It has to be said that the setting of the church adds to its appeal. Around it are narrow streets, the old Market Place, the newer (1902-4) Market Hall, the old Grammar School (also brick, 1583-5), Trinity House, and a host of Victorian and earlier buildings.

The January day on which I took my photograph was cold and bright. I liked the way Holy Trinity's tower and the upper parts of the nave, transepts and chancel appeared to rise towards the light out of the deep shadows of the surrounding streets.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 18mm (27mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/125 sec

ISO:100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

church,

Holy Trinity,

Hull,

Kingston upon Hull,

medieval

Tuesday, October 07, 2014

Classical busts and wash drawings

click photo to enlarge

I was talking with a farmer a while ago and during the course of the conversation I observed that I knew more about medieval ploughing than I did about the modern methods. It was only when I reflected on that conversation some time later that I realised there are quite a few things from the past that I know about in some detail, but when it comes to the modern equivalent I am rather less well informed.

One such example that came to mind recently is the training of architects. It was this Georgian classical bust on the stairwell of the Maister House in Hull that prompted the thought. The work is one of two pieces on brackets that flank a large statue of "Ceres" by John Cheere. The smaller works may be his too. However, I didn't check their provenance because the lighting of this bust, when I reviewed my photograph on the camera screen, immediately made me think of the ink wash and watercolour drawings of the architectural students of the Ecole des Beaux Arts. More particularly I thought of "An Antique Relief" by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, painted c.1886 when he was a student at the Glasgow School of Art. The ability to draw well and render accurately used to be part of the training of architects. It was need not just to sketch basic ideas, to depict their vision before it was constructed, but also to communicate large and small details to the builders so they could turn ideas into reality. I imagine drawing must play a part still in architectural training but technology in the form of the computer probably figures just as large.

So, to make the bust look more like an eighteenth or nineteenth century architect's ink wash I converted my photograph to black and white and slightly increased the contrast.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 35mm (52mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f4

Shutter Speed: 1/60 sec

ISO:6400

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

I was talking with a farmer a while ago and during the course of the conversation I observed that I knew more about medieval ploughing than I did about the modern methods. It was only when I reflected on that conversation some time later that I realised there are quite a few things from the past that I know about in some detail, but when it comes to the modern equivalent I am rather less well informed.

One such example that came to mind recently is the training of architects. It was this Georgian classical bust on the stairwell of the Maister House in Hull that prompted the thought. The work is one of two pieces on brackets that flank a large statue of "Ceres" by John Cheere. The smaller works may be his too. However, I didn't check their provenance because the lighting of this bust, when I reviewed my photograph on the camera screen, immediately made me think of the ink wash and watercolour drawings of the architectural students of the Ecole des Beaux Arts. More particularly I thought of "An Antique Relief" by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, painted c.1886 when he was a student at the Glasgow School of Art. The ability to draw well and render accurately used to be part of the training of architects. It was need not just to sketch basic ideas, to depict their vision before it was constructed, but also to communicate large and small details to the builders so they could turn ideas into reality. I imagine drawing must play a part still in architectural training but technology in the form of the computer probably figures just as large.

So, to make the bust look more like an eighteenth or nineteenth century architect's ink wash I converted my photograph to black and white and slightly increased the contrast.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 35mm (52mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f4

Shutter Speed: 1/60 sec

ISO:6400

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

architectural drawing,

bust,

Classicism,

Hull,

Maister House

Sunday, September 14, 2014

Photographic parts and the whole

click photo to enlarge

I favour compositions that feature the whole of something - a building a flower, a tree, etc. It may be asymmetrically placed, sometimes it's centrally located, it may be small, or it can just about fill the frame. But, nine times out of ten I include a complete and recognisable subject in my compositions. On the other occasions I deliberately don't! Moreover, when I photograph a fragment, or multiple fragments of several objects I'm fighting my natural predilection.

Take today's photograph. I took a couple of shots of all of this ornamental fountain in Queen's Gardens, Hull, with its wind-blown jets of water partly obscuring Christopher Wray's magnificent Dock Offices of 1867-71. However, the compositions didn't satisfy me; there was too much in the frame and no definite visual focus. So I tried a composition featuring part of the fountains and just two of the three domes in a composition that has a strong diagonal element running from the top left to the bottom right. It proved much better. And, with a fairly contrasty black and white conversion that made the best of the dull day I produced a monochrome shot that pleases me more than most of my recent efforts.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 35mm (52mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/320 sec

ISO:100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

I favour compositions that feature the whole of something - a building a flower, a tree, etc. It may be asymmetrically placed, sometimes it's centrally located, it may be small, or it can just about fill the frame. But, nine times out of ten I include a complete and recognisable subject in my compositions. On the other occasions I deliberately don't! Moreover, when I photograph a fragment, or multiple fragments of several objects I'm fighting my natural predilection.

Take today's photograph. I took a couple of shots of all of this ornamental fountain in Queen's Gardens, Hull, with its wind-blown jets of water partly obscuring Christopher Wray's magnificent Dock Offices of 1867-71. However, the compositions didn't satisfy me; there was too much in the frame and no definite visual focus. So I tried a composition featuring part of the fountains and just two of the three domes in a composition that has a strong diagonal element running from the top left to the bottom right. It proved much better. And, with a fairly contrasty black and white conversion that made the best of the dull day I produced a monochrome shot that pleases me more than most of my recent efforts.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 35mm (52mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/320 sec

ISO:100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

black and white,

Dock Offices,

fountain,

Hull,

Queen's Gardens,

Yorkshire

Thursday, June 26, 2014

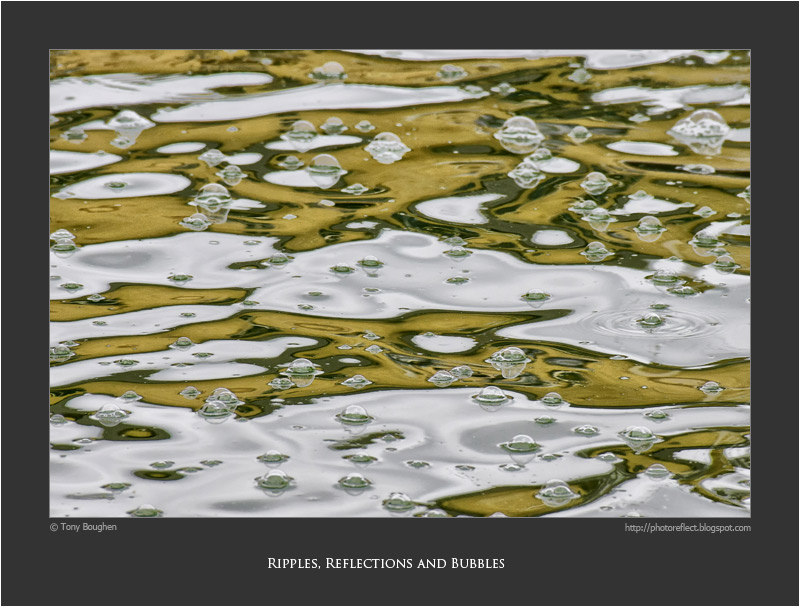

Ripples, reflections and bubbles

click photo to enlarge

I've been doing less photography than is usual for me in recent months - other activities and interests have been consuming more of my time. And, as a consequence, I think my photographic eye has become somewhat dulled. The fact is, with photography as with many other undertakings, pursuing the act on a regular basis is the only way of maintaining an acceptable level of performance. Just as the soccer player or musician loses their touch without regular training, matches or performances, so too does a photographer find it harder to see subjects once he or she begins taking fewer shots.

I've experienced troughs of this kind before. The way I dealt with it then was to keep on snapping or - and this works for me but may not for others - by giving more attention to seeking out semi-abstract subjects. I don't know why this should be effective, but it has been in the past and it may help again. My shot with the out of focus barbed wire was an example of my endeavours in this direction, and so too is today's photograph. I'd been photographing the large, formal fountain in Queen's Gardens, Hull, and producing nothing of interest. So, in pursuit of my short-term aim I concentrated on the reflections and bubbles produced by the falling drops of water. Not the best example of this genre that I've produced, but better than most of what I've been producing lately.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 140mm (210mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/250 sec

ISO:280

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

I've been doing less photography than is usual for me in recent months - other activities and interests have been consuming more of my time. And, as a consequence, I think my photographic eye has become somewhat dulled. The fact is, with photography as with many other undertakings, pursuing the act on a regular basis is the only way of maintaining an acceptable level of performance. Just as the soccer player or musician loses their touch without regular training, matches or performances, so too does a photographer find it harder to see subjects once he or she begins taking fewer shots.

I've experienced troughs of this kind before. The way I dealt with it then was to keep on snapping or - and this works for me but may not for others - by giving more attention to seeking out semi-abstract subjects. I don't know why this should be effective, but it has been in the past and it may help again. My shot with the out of focus barbed wire was an example of my endeavours in this direction, and so too is today's photograph. I'd been photographing the large, formal fountain in Queen's Gardens, Hull, and producing nothing of interest. So, in pursuit of my short-term aim I concentrated on the reflections and bubbles produced by the falling drops of water. Not the best example of this genre that I've produced, but better than most of what I've been producing lately.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 140mm (210mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/250 sec

ISO:280

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

bubbles,

fountain,

Hull,

reflections,

semi-abstract,

water

Monday, June 16, 2014

Superstore gull

click photo to enlarge

Pointing my camera at the corner of a Tesco Extra superstore in Kingston upon Hull my eye was drawn to some unexpected movement. It turned out to be a juvenile herring gull perched on the dark metal frame of the glazing, an incongruous shape against the stark regularity of the architecture. What was it doing? Its repeated pecking motions at the glass suggested two possibilities. Perhaps it was trying to break through and help itself to the mounds of food piled high on the shelves within. Or, more likely, it was behaving either aggressively or amorously towards its own reflection. Whatever the reason for its presence on its perch injected a note of idiosyncrasy and contributed a point of interest for a photograph of the man-made background. Something that I've found gulls, and in fact birds in general, sometimes do.

© Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 27mm (40mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/80 sec

ISO:100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Pointing my camera at the corner of a Tesco Extra superstore in Kingston upon Hull my eye was drawn to some unexpected movement. It turned out to be a juvenile herring gull perched on the dark metal frame of the glazing, an incongruous shape against the stark regularity of the architecture. What was it doing? Its repeated pecking motions at the glass suggested two possibilities. Perhaps it was trying to break through and help itself to the mounds of food piled high on the shelves within. Or, more likely, it was behaving either aggressively or amorously towards its own reflection. Whatever the reason for its presence on its perch injected a note of idiosyncrasy and contributed a point of interest for a photograph of the man-made background. Something that I've found gulls, and in fact birds in general, sometimes do.

© Tony Boughen

Camera: Nikon D5300

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 27mm (40mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/80 sec

ISO:100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

architecture,

contrast,

herring gull,

Hull,

store

Saturday, November 16, 2013

The beauty of church vaulting

click photo to enlarge

The vaulting that graces many a church and cathedral ceiling, especially inside a tower, is a recurring topic on this blog. I am fascinated by the variations on a theme that medieval masons and carpenters wrought in their desire to beautify the space above the worshippers' heads such that an upward glance really did feel like a glimpse of heaven. Architectural historians have created a whole specialised vocabulary to describe the development of vaulting down the centuries from its beginnings in simple barrel vaulting, to groin vaults, rib vaults, quadripartite and sexpartite vaults, vaults with tiercerons and liernes, culminating in the glories of stellar vaults and fan vaults.

The purpose of vaulting is to take some of the weight of a roof or tower above and distribute it laterally on to arches, walls, piers and columns. In the crossing vault shown above the ribs that form fans stretching from the centre to the four corners are instrumental in achieving this weight transference. However, this vaulting also has a central star pattern made by the addition of short decorative ribs called liernes. Clearly it is a design that seeks to impress with its beauty as well as do an architectural job of work. In fact, all is not what it seems with this vaulting. The tower of Holy Trinity was built during the period 1500-1530 on a raft of oak trees for the lack of any firm bedrock below. These were replaced by concrete in 1906. The vaulting, however, was erected as late as the 1840s, and the beautiful, rich paintwork must surely originate from that time - a mixture of medieval ideas and Victorian interpretation and development of those ideas. When I magnify my photograph I can see that the infill is timber planks so I imagine the ribs must be timber too. This vaulting will have replaced an earlier ceiling. That may have been stone, but is more likely to have been timber too. I've often seen fine Victorian work that replaced an insensitive, flat Georgian ceiling (itself inserted in place of the medieval original) though I've no reason to believe that is the case here. In fact, timber roofs were more widespread in England during the medieval period than in any other North European country and exhibit a unique ingenuity and beauty. Here, at Holy Trinity, the wood mimics painted stone and is none the worse for that.

The organ pipes on north and south sides of the crossing belong to the largest parish church organ in Great Britain. The oldest of the more than 4,000 pipes date from 1756 and are by Johannes Snetzler.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f1.8

Shutter Speed: 1/30

ISO: 800

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

The vaulting that graces many a church and cathedral ceiling, especially inside a tower, is a recurring topic on this blog. I am fascinated by the variations on a theme that medieval masons and carpenters wrought in their desire to beautify the space above the worshippers' heads such that an upward glance really did feel like a glimpse of heaven. Architectural historians have created a whole specialised vocabulary to describe the development of vaulting down the centuries from its beginnings in simple barrel vaulting, to groin vaults, rib vaults, quadripartite and sexpartite vaults, vaults with tiercerons and liernes, culminating in the glories of stellar vaults and fan vaults.

The purpose of vaulting is to take some of the weight of a roof or tower above and distribute it laterally on to arches, walls, piers and columns. In the crossing vault shown above the ribs that form fans stretching from the centre to the four corners are instrumental in achieving this weight transference. However, this vaulting also has a central star pattern made by the addition of short decorative ribs called liernes. Clearly it is a design that seeks to impress with its beauty as well as do an architectural job of work. In fact, all is not what it seems with this vaulting. The tower of Holy Trinity was built during the period 1500-1530 on a raft of oak trees for the lack of any firm bedrock below. These were replaced by concrete in 1906. The vaulting, however, was erected as late as the 1840s, and the beautiful, rich paintwork must surely originate from that time - a mixture of medieval ideas and Victorian interpretation and development of those ideas. When I magnify my photograph I can see that the infill is timber planks so I imagine the ribs must be timber too. This vaulting will have replaced an earlier ceiling. That may have been stone, but is more likely to have been timber too. I've often seen fine Victorian work that replaced an insensitive, flat Georgian ceiling (itself inserted in place of the medieval original) though I've no reason to believe that is the case here. In fact, timber roofs were more widespread in England during the medieval period than in any other North European country and exhibit a unique ingenuity and beauty. Here, at Holy Trinity, the wood mimics painted stone and is none the worse for that.

The organ pipes on north and south sides of the crossing belong to the largest parish church organ in Great Britain. The oldest of the more than 4,000 pipes date from 1756 and are by Johannes Snetzler.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f1.8

Shutter Speed: 1/30

ISO: 800

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

church,

crossing tower,

Holy Trinity,

Hull,

Kingston upon Hull,

medieval,

ribs,

vaulting,

Victorian decoration

Friday, December 07, 2012

Staring at stairs

click photo to enlarge

When I looked in my edition of the Oxford English Dictionary I initially couldn't find the word "stairwell". But, after a bit of digging, it turned up towards the end of the "stair" entry. The definition was as I imagined, namely "the shaft containing a flight of stairs." It seems to be one of those words that is slowly falling out of use, being replaced by "stairs" and "staircase", neither of which properly describes the architectural space, but rather the structure for ascent and descent that it holds.

I was pondering this word as I processed my photograph of a glass-walled stairwell in some Hull offices, a shot that I'd taken during the early evening on my last visit to the Yorkshire city. It occurred to me that I had to - wait for it - "stare well" before I took my photograph, but that no one in the building took the slightest bit of notice of me. That was quite a contrast with what happened when I took an early evening photograph of a glass walled building in the private public space that is "More London" a couple of years ago. On that occasion a security guard came out and asked me to stop taking photographs. I thought then, as I thought when I took the photograph in Hull, that anyone who doesn't want to be photographed inside the building in which they work really shouldn't choose one with glass walls. If you inhabit a goldfish bowl you can't complain if people stand and look at you or take photographs, especially if the land outside is public space. Besides, doesn't an architect, in designing in this way, seek to both satisfy the practical and aesthetic needs of the client and offer the locality a building worth looking at? And can we be blamed if we look - or take photographs? Those in this office certainly seemed untroubled by me taking shots from nearby and further away. Would that London offices were as accommodating!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 80mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/80

ISO: 1000

Exposure Compensation: -1.00 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

When I looked in my edition of the Oxford English Dictionary I initially couldn't find the word "stairwell". But, after a bit of digging, it turned up towards the end of the "stair" entry. The definition was as I imagined, namely "the shaft containing a flight of stairs." It seems to be one of those words that is slowly falling out of use, being replaced by "stairs" and "staircase", neither of which properly describes the architectural space, but rather the structure for ascent and descent that it holds.

I was pondering this word as I processed my photograph of a glass-walled stairwell in some Hull offices, a shot that I'd taken during the early evening on my last visit to the Yorkshire city. It occurred to me that I had to - wait for it - "stare well" before I took my photograph, but that no one in the building took the slightest bit of notice of me. That was quite a contrast with what happened when I took an early evening photograph of a glass walled building in the private public space that is "More London" a couple of years ago. On that occasion a security guard came out and asked me to stop taking photographs. I thought then, as I thought when I took the photograph in Hull, that anyone who doesn't want to be photographed inside the building in which they work really shouldn't choose one with glass walls. If you inhabit a goldfish bowl you can't complain if people stand and look at you or take photographs, especially if the land outside is public space. Besides, doesn't an architect, in designing in this way, seek to both satisfy the practical and aesthetic needs of the client and offer the locality a building worth looking at? And can we be blamed if we look - or take photographs? Those in this office certainly seemed untroubled by me taking shots from nearby and further away. Would that London offices were as accommodating!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 80mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/80

ISO: 1000

Exposure Compensation: -1.00 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

architecture,

curtain wall,

definitions,

Hull,

offices,

staircase

Subscribe to: