As they used to say in the cinema after the B movie and before the main feature, "Ladies and gentlemen there will be a short intermission." However, you needn't worry, I won't be walking around selling ice-cream and popcorn by torch light.

This morning my computer's internal hard drive died. To be more accurate it went up in smoke. Not a lot of smoke admittedly, but enough to notice and enough to make a stink in my study. I've ordered a replacement, and when it arrives I'll be engaged in the joyless task of re-installing the operating system, loading my programs, installing hardware drivers, etc. My backup procedures saved most of my data, but inevitably I lost a few recent, not very important bits and pieces.

I could carry on blogging using my second desktop or the laptop, but I'm going to take this opportunity to spend some time tidying up the older machine. It is in pretty much the state it was when it was superseded, and, with a bit of work I can free up some space and speed it up a touch as well. If things go well in that department I may start posting from it (as I did before I built my new machine) in a couple of days time. In any event this intermission should not be too long.

Wednesday, January 28, 2009

Tuesday, January 27, 2009

An angel roof

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeThe Gothic style of architecture that prevailed from the twelfth century until the fifteenth century was an international style in much the same way that the styles of the twentieth and twenty first century have been. It's true that it was largely confined to Europe rather than the world in general, but across England, France, Germany, Italy and many other nations the same construction methods, building forms and decorative devices were used. There were regional differences, but these were within the overall style, and made one nation's Gothic different in detail rather than substance.

English Gothic developed two main differences that made it stand out from that produced by other nations. In the fifteenth century the style turned towards what was later called "Perpendicular", a period when the ogee curves and naturalistic carving of earlier years was abandoned and replaced by repeated, flat "panel" tracery. The whole appearance of buildings was lighter due to bigger windows and larger spaces, and the refined decoration gave it a more austere look. This change was not seen in continental Europe. The other difference in English Gothic was the preference for wooden ceilings and roofs over stone vaulting. The great cathedrals and monasteries did have stone vaulting that became more intricate over time, as happened elsewhere in Europe. However, parish churches rarely used it, preferring quite sophisticated timber roofs of varying constructional types. The high-point in elaboration was undoubtedly the double hammer-beam design, a form that spanned a wide space without the need for a long tie-beam to bridge the gap from wall to wall. Other variations include the trussed rafter roof, the tie-beam design, the collar braced design, the barrel roof and the single hammer beam roof.

Today's photograph shows an example of this fine woodwork - a tie-beam nave "angel roof" with brackets resembling arch-braces - at All Hallows church (sometimes called All Saints) at Dean in Bedfordshire. The structure has been restored: some of the rafters, purlins and boarding have been replaced, but the principal members remain from the 1400s when it was first erected. Beautification was as important as utility to the people who created this roof. The decoration includes large angels that hold the Instruments of the Passion and musical instruments, infill of stylised foliage, dentil-like carving, bosses with birds, angels, rope and other devices and wall-plate friezes of leaves and angels. Such roofs were usually brightly painted and offered a glimpse of heaven to those in the congregation who turned their eyes upward. Today they continue to offer a marvellous sight to the interested visitor and photographer.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 11mm (22mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f2.8

Shutter Speed: 1/8

ISO: 200

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

All Hallows,

angel roof,

Bedfordshire,

church,

Dean,

Gothic architecture,

roof,

tie-beam,

timber construction

Sunday, January 25, 2009

Primordial soup and chilli

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeScientists say that the earliest traces of life on earth came into existence in a primordial soup. Thinking about it, and looking at mankind's trajectory today, I suppose the soup can't have been anything terribly sophisticated: certainly not a lobster bisque, clam chowder or watercress and Stilton. Perhaps it was a kind of hot mulligatawny, though I doubt it: far more likely is something involving a sludge of brown lentils.

But what if the scientists are wrong? What if, rather than soup, life evolved in some chilli con carne that, after an interstellar journey of unimaginable distance and duration, impacted with our planet? I know what you're thinking. How could a spicy bean and meat dish of Mexican origin get into space before the Mexican people have even evolved, and furthermore Mexico hasn't got any space rockets? Now I recognise those are good arguments against my thesis, but then how do you explain people's increasing liking for chilli, not just as a spice, but as a vegetable and a medicine? Do you think chilli would have spread, exponentially, from the Americas to every corner of the world, have found its way from savoury meals into corn snacks, ice cream, chocolate and other exotica, without there being a biological imperative underpinning the all-conquering spice? No, it was clearly sent to earth, and out of it came the life that now dominates our planet. It must have lain dormant until mankind evolved sufficiently to spread its essence throughout the world.

If, by some remote chance, you're still reading this rubbish you must be wondering how I know all this. Well, it came to me as I photographed a portion of chilli con carne in a plastic tub that was part of a batch cooked and frozen a few weeks ago. It was on the kitchen work surface, thawing out for our evening meal, and, as I noticed the beads of water on the inside of the plastic lid, with the glow of the chilli behind it, an image of the one true and original con carne - a cluster of asteroid-like shapes each ringed with ice on the epic journey through space - came to me. Look closely at my photograph and you'll see it too! Do you think I have enough material here to start a cult?

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 35mm macro (70mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f11

Shutter Speed: 0.5 seconds

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.0 EV

Image Stabilisation: Off

Labels:

chilli con carne,

macro,

origins of life,

primordial soup,

spoof

Saturday, January 24, 2009

Shooting the sun

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlarge"Always take photographs with your back to the sun." That's the first piece of photographic advice I remember reading as a teenager. And useless advice it was too! Follow that rule when photographing people and you end up with an image of people squinting at the camera. Other subjects look floodlit, flat and boring. I soon learned that much better photographs result when you have the sun falling on your subject from the left or right giving shadows that model whatever it is that you are shooting. Later still in my photographic development I appreciated the value of getting the camera pointing quite close to the sun, and producing contre jour and silhouette effects.

In recent years, since the advent of digital photography, I've found myself deliberately including the sun in shots for the striking and slightly unpredictable effects that ensue. The sun in the image acts as a very strong compositional element, and can be a useful counterweight to a more tangible subject elsewhere in the frame, as here and here. I tried it again the other day as I walked through the Lincolnshire countryside below a cold sky filled with the graffiti of passenger jets. I tried a few different exposures, and settled on this one taken with a shutter speed of 1/4000 second, as the best of the bunch. It has quite a strong "starburst" around the sun, a couple of aberrations produced by light interacting with the glass, and an interesting mix of colours ranging from almost black at the top, through blues, whites and orange. It's not a shot that I can say I carefully organised before pressing the shutter, but its unpredicted qualities make for an image that I find quite pleasing.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 11mm (22mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/4000

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

contre jour,

photography,

silhouettes,

sky,

starburst,

sun,

vapour trails

Friday, January 23, 2009

Surfleet Seas End

click photos to enlarge

click photos to enlarge

It's not too difficult to find a place in Britain where time seems to have stood still. When I walk the barren uplands of the Pennines, the Lake District, or the North York Moors I often think that I'm looking at a scene that people saw in pretty much the same way 100, 500 or 1,000 years ago (the scream of RAF Typhoons, Tornados and Harriers permitting).

In towns and cities there are areas, corners, streets and views that have been sensitively preserved where people can project themselves backwards to the time of the Tudors, the Georgian era, Victorian times or the early C20. In and around our great medieval cathedrals "time travel" of a greater order is possible. The Lincolnshire town of Stamford is popular with film-makers because it's relatively easy to film actors in front of eighteenth century buildings without making very many changes to the structure's appearance - perhaps the removal of the odd telephone wire or electrical doorbell is all that is required. Of course, the nearer one comes to the present time, the easier it is step back. If you want to see a street that looks like it did in the 1930s or 1950s, you can find them with relative ease, though you might have to overlook the uPVC windows and doors, and the front gardens turned into car parking spaces.

On England's east coast it is still possible to come across little groups of modest, single-storey, wooden houses built in the inter-war and immediate post-WW2 years. Here one gets the feeling of being transported back to those austere days where pleasures were simpler and a holiday by the seaside involved ice-cream, catching fish, sailing a toy yacht, and fish and chips in a cliff-top cafe, rather than jetting off to some sun-drenched beach in the Mediterranean or even further afield. A few of these structures are permanently inhabited, but most are used for weekends and holidays. The area around Flamborough Head in Yorkshire has a good collection. These were much more numerous than now, but a lot have succumbed to the weather, to rot, neglect, and the desire for more exotic breaks. Others, however, have been restored with the aim of making them look like they did when first built. Many have been "updated", with brick replacing wood walls, and uPVC taking over elsewhere.

Today's photograph shows this type of recreational dwelling at an inland location. Surfleet Seas End in Lincolnshire, despite its name, is a few miles from coast, at the point where the River Glen (shown in the images) meets the River Welland before the latter empties into the North Sea via The Wash. A sluice prevents the ingress of tidal water, and keeps the river here at a stable level. This community of wooden structures, mainly used at weekends and holidays, has grown up to take advantage of the pleasant waterside location. My two images show it at different times of year. The first was taken yesterday as the sky cleared in the late afternoon after rain, a type of weather that I particularly like for photography. The second was taken on a hot summer morning for the colour, the reflection and the symmetry.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Image 1

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 11mm (22mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/320

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Image 2

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 14mm (28mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/400

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

holidays,

Lincolnshire,

River Glen,

Surfleet Seas End,

wooden shacks

Thursday, January 22, 2009

Converging verticals

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeOne of the problems in photographing tall buildings is converging verticals. If you want to include most or all of a tall structure you have to point the camera upwards causing the verticals to converge on a "vanishing point". In the days of film, and still today, photographers used "tilt-shift" lenses that can be adjusted to correct this effect. However, they are prohibitively expensive for most of us, and are largely confined to professional architectural photographers. But, the advent of digital imaging allows anyone to correct verticals in software with varying degrees of success.

Today's photograph shows my attempt to secure an image of the west elevation of the the 282 feet high medieval Gothic church of St Wulfram at Grantham in Lincolnshire. A gateway into the churchyard, nearby buildings and trees prevent the photographer moving back far enough to photograph the building without tilting the camera upwards. So, I took a shot from as far back as I could, knowing that I wanted to "process" it back to vertical. Back home at the computer it was easy enough to correct the verticals, but that resulted in a very vertically compressed image in need of elongating with bicubic interpolation. The width of the church is 79 feet, so to get the proportions right I had to stretch the building until it was 3.6 times as tall as it was wide. But, because I'd tilted the camera the relative sizes of parts of the structure, particularly the spire, were wrong in the original shot, and stayed wrong in the "corrected" version: even though it was "right" it looked wrong. Consequently I compromised with this version that understates the height of the church but looks more correct. In fact, in my photograph St Wulfram's is 2.6 times as tall as it is wide, and though it makes for a reasonable picture, it is a definite failure in architectural photographic terms.

This example of the problem of "converging verticals" is quite extreme: most photographs that need correction are able to be amended without the problems encountered here. Why was I doing it? Well, many consider this spire, the third tallest on a medieval parish church after Louth and St Mary Redcliffe, Bristol, to be the finest example in Britain. Though it has much to admire I wouldn't go that far, preferring the broach spires of the fourteenth century to later examples such as this one. However, I thought that if I could see it without the distortion that you experiences during a visit as you look up, and as you see it in an uncorrected photograph, perhaps my appreciation of its architecture would change. So far it hasn't.

photograph & text (c) T.Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 11mm (22mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/250

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, January 21, 2009

Explaining photographs

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeSometimes the hardest thing about photography is explaining why you take a particular image. With snaps of family and friends no explanation is needed. Images taken on holiday are self-evidently a record of an experience. My shots of churches and church architecture are made in connection with my hobby, and some of these I post because they have a wider application as a picture with interesting content and (I hope) good composition, lighting, etc.

I do quite a few landscapes, a genre that many will readily accept as a legitimate for photography. So too with images of plants, flowers, still lifes, etc. The semi-abstract shots I take sometimes require explanation, but most people are sufficiently visually literate to recognise the tradition that such images come from. The photographs I have most trouble with are images like the one above. I was walking over the rolling Lincolnshire hills when I spotted this forestry planatation of regularly spaced trees. As I approached it I kept taking shots of the trees: some with sky, some with just the repeated verticals. At one point a straggly old oak in the hedge that is in front of the plantation caught my eye, and I included this with the verticals of the young trees by way of contrast, a free spirit against the background conformity! However, when I noticed the high flying airliner coming into the equation I made this image. It's the shot I like best out of the eight or so that I took trying to get a decent composition out of this subject.

Why did I take it, and why do I like it? I appreciated the contrast between the verticality of the trees and the horizontal passage of the plane. I also liked the significant detail that it brought to the expanse of blue. The fact that the airliner isn't something that is noticed on first viewing pleased me too, as well as the fact that once you have seen it then it becomes an essential part of the composition. So I took the shot and like it for that group of reasons, for its quirky simplicity. Of course, there's no requirement on anyone to explain their photographs: they can stand (or fall) on their own merits. But, as far as the image above goes that's my view, but yours may well differ!

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 40mm (80mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/640

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

airliner,

composition,

photography,

trees

Tuesday, January 20, 2009

Ropsley church

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeWhen I approach a church that I've never visited before, such as the one shown in this photograph, St Peter at Ropsley, Lincolnshire, I do two things. First, I take a photograph of the exterior. I then know that this marks the point in my sequence of images when I began shooting at a new church: important if you visit six or seven during the course of the day. Then I stand and stare. What I'm doing as my gaze ranges over the building is trying to read something of its history from the evidence that is shown on its exterior.

Here I immediately noticed the Decorated style (C14) of the fine broach spire, and the late C15 porch with its too-tall (for my taste) pinnacles. I guessed the south aisle was C15 too from the style of its windows, and wondered whether the extension at the side of the chancel was a chantry chapel. The clerestory clearly came at a point when the church was enlarged, but was it C14 or C15? Of course, when you enter the building the nave arcades are usually revealing, and here was no exception - the south columns and arches C13, like the chancel arch. Some windows on the north side looked post-medieval. However, churches often have the capacity to surprise a visitor, and Ropsley is no exception, because the nave corners show evidence of Anglo-Saxon "long and short work", and the north aisle has obviously Norman work. So, the Gothic exterior surrounds and extends a Romanesque building from the C11.

None of that early work is obvious in this black and white image taken from the south-east corner of the churchyard. This is usually the best location for a shot of a complete English church, providing the church council hasn't planted trees (particularly dark, dense yews) that obscure this quarter! However, Ropsley is quite exposed, making a fine sight on its slight rise, its surroundings restricted to a soft greeensward and a small forest of leaning gravestones that include many excellent slate examples from the C18 and early C19.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 14mm (28mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/320

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Monday, January 19, 2009

Kyme Priory

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeI've often wondered how different our view of English Gothic architecture would be if Henry VIII hadn't broken with Rome, passed the Act of Supremacy (1534) setting him at the head of the English church, and passed the two Acts (1536 and 1539) that suppressed the monasteries. Instead of cathedrals and parish churches (in the main) being the buildings that define and trace Gothic architecture, we'd also have large, complete, monasteries, abbeys and priories with their major churches and ancillary buildings added to the mix. And, these buildings would have been added to beyond the Gothic period, up to the present day perhaps, making them some of the most significant religious buildings in Britain.

However, there are things that we would have lost. The romantic, crumbling, Cistercian ruins of places such as Rievaulx Abbey and Fountain's Abbey would not have been there to inspire our painters and poets: William Wordsworth's "Tintern Abbey" wouldn't have seen the light of day. Money that was channelled into other churches and cathedrals would have been used for monasteries, and the absence of the "quarries" that the redundant sites became, that provided building stone for nearby houses and farms would have resulted in quite different vernacular architecture in the areas surrounding these great churches. Furthermore, we wouldn't have seen fragments of these large buildings escaping destruction to provide the parish church for the place in which they were located, as happened with many, including Bolton Abbey and Kyme Priory, Lincolnshire (see today's photograph).

The present church of St Mary & All Saints at South Kyme is made from the west end of the south aisle and part of the south section of the nave of the priory. The rest of the Augustinian structure was swept away at the Dissolution. The building we see today was tidied up in 1888 by C. H. Fowler. The remains of architectural interest include the fine Norman south doorway, an original south porch, C14 windows, C15 glass fragments, some fascinating monuments, a headless Virgin in a niche above the porch entrance, and some very interesting pieces of Anglo-Saxon carving with work similar to the designs on Celtic and Irish illuminated manuscripts, suggesting a date of C7 or C8.

My photograph was taken on a late afternoon in January as the sun was heading for the horizon. The over-sized windows hint at the structure that gave birth to the village's present parish church, but Fowler's transformation pulls the design together very well, and the untrained eye might see it as a modest village church topped with a bell-cote because the funds wouldn't run to a tower. A black and white treatment seemed to suit the location and composition better than colour, and I increased the contrast with the digital equivalent of a red filter.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 16mm (32mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/125

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Saturday, January 17, 2009

Enjoying confusion

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeFor much of my life, as an educator, my task was to make clarity out of the complexity and confusion in the minds of students. When I ascended the hierarchy of management I was expected to do the same with the staff that I deployed. It's a laudable aim in that line of work, and elsewhere in the world. Minds greater than mine are attempting to do just that with the banking system, and I hope, for all our sakes, that they succeed.

And yet, perhaps because it seems mankind's unending task to explain the world to itself, there is sometimes great pleasure to be had in contemplating confusion rather than interpreting it. Nowhere is this more evident than in the arts. Film, novels, fine art and photography revel in presenting confusion, or apparent confusion, to the viewer and reader. That confusion can be interpreted, the "meaning" extracted, and an attempt made to understand it; or it can enjoyed at a visceral, literal level, as elemental, unsettling perplexity.

Today's photograph presents confusion in visual form. I could explain what is going on in the image, how the architecture works, what is being reflected, what is inside the glass and what is outside. But I won't. When I saw this scene I enjoyed it for what it was, a puzzling, disorienting arrangement of forms, and that is how I present it.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 150mm (300mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/320

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

confusion,

glass,

reflections,

workman

Friday, January 16, 2009

Sculpture as perch

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeWhenever I visit Whitby in North Yorkshire I trudge up the steps of West Cliff, to the statue of Captain Cook at the summit, and gaze across the harbour at St Mary's Church and the Abbey. Then I turn and look at the figure of Cook himself and remember that there has NEVER, EVER been an occasion that I done this without there being a herring gull sitting on his head undermining the dignity of his pose, his fine clothes and his serious countenance, making him look absolutely ridiculous, not to say risible!

On my forays into Boston, Lincolnshire, I frequently stop and look up from the Market Place at the tower of St Botolph's church. On these occasions my gaze passes the statue of Herbert Ingram, a Swineshead man, founder of the Illustrated London News and Member of Parliament for Boston. I invariably find that he too is topped by either a black-headed gull or a pigeon that is intent on turning his hair white. In the recent past I've photographed three sculptures with birds on them, two in Southport (the other here) and one in Rotherhithe, London. I used to fondly imagine that gulls perched on statues of people to get their own back for the hard time we give them. However, finding birds standing on bird statues rather scotches that theory.

Today's photograph shows both black-headed gulls and feral pigeons making use of the handy perches provided by the outstretched bodies of Stephen Broadbent's 2002 sculpture in Lincoln, entitled "Empowerment". Despite the fact that the two figures of the piece reach out to one another across the River Witham I'm guessing that neither the sculptor nor those who commissioned it thought too much about its usefulness to the local avian population. I think this sculpture is better than many, but it's not one that especially grabs me. I do, however, dislike its title: it sounds like its been dreamed up by a council committee that lives for the latest jargon. However, the birds of this part of Lincoln love the sculpture. On one occasion I counted almost thirty crammed onto its "perching points". I'm not particularly keen on the supports for the two figures in this sculpture, but I quite like the two almost touching figures, so I made them (along with their feathered friends) the subject of my photograph.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 40mm (80mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/800

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

birds,

Empowerment,

Lincoln,

Lincolnshire,

public sculpture,

Stephen Broadbent

Thursday, January 15, 2009

Reflecting on the Brayford Pool

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeAbout a year ago I visited Lincoln for the first time in twenty years or so. That's a long time in the life of a small city, and I noticed quite a few changes on my return. Whilst I was there I took a photograph that was subsequently selected for a London exhibition. It shows a bicycle, semi-submerged on a walkway at the Brayford Pool which was experiencing particularly high water. The last time I'd been in that location it was fairly derelict, with disused quays and crumbling buildings in evidence. But since the 1980s there has been "regeneration". A marina for pleasure craft has been created and university buildings, hotels, cafes and the like have sprung up. On my visit a year ago I didn't have time to stop, look and think about what has happened at Brayford. Yesterday I did. My conclusion is that whoever sanctioned the structures and planning of the the development that has taken place, the marina excepted - it's fine, should be ashamed of themselves.

The Brayford Pool today is surrounded by a group of buildings for which the term banal would be high praise. I made two leisurely circuits of the area and struggled to find anything of architectural merit. Quite the worst building is the Holiday Inn, a "warehouse" look-alike clearly imagining that it both recalls the Rank Hovis mill that it replaced, and is appropriate to the waterside setting. In fact, it's toy-town architecture at its worst. Running it a close second is the large university building directly across the water, a grim, uninspiring amalgam of materials and forms with a desert of drab paving set before it. Of marginal interest is a (1960s?) reinforced concrete framed building with a "hyperbolic parabaloid" roof, but a new rectilinear glazed wall that has been inserted seems to exist independently of the original skeleton, only acknowledging it by being centred on its twin column support. Perhaps the best building is the curved Hayes Wharf with its irregularly placed groups of slats, positioned near the flyover: it's a good structure for that site, and offers style and interest. Overall however, as a piece of urban planning, the renovation of Brayford Pool is an opportunity missed. Even the small details are poor: the pedestrian route around the main pool is gravel and mud on the south side, is badly waymarked, weaves through and around buildings in a confusing way, and, unforgivably, involves going up to the busy, noisy flyover to complete the main circuit. And quite why, in the twenty first century, in an area designed to attract people, we are still being asked to scurry, rat-like, through an underpass (see today's photograph) beggars belief!

photograph & text (c) T.Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 11mm (22mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/100

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -2.0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, January 14, 2009

Birdwatching, photography and reeds

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeIt struck me the other day that photographers are quite similar to birdwatchers in the way they choose to pursue their hobby.

Birdwatchers fall into two main groups. There are those who study a particular local patch, walking the same routes year after year in different seasons and at different times of day, learning which birds favour which spots and when, noting the unfamiliar as their eye becomes attuned to the familiar terrain. Such people also, periodically, travel a bit further afield and benefit from seeing new species in different surroundings. Often birdwatching of this kind is a solitary pursuit, or is undertaken with a partner or friend, and builds a knowledge of bird life in a particular locality over time. Then there are those who tear around the countryside by car, briefly dropping into favoured spots, scanning the usual places before screeching off to the next locations, contacting other birdwatchers to find out if any rarities have been seen within striking distance. These birdwatchers compile lists of all sorts - birds seen from their home, birds seen in their country, birds seen in their lifetime, etc. Trips to far-flung places and abroad, to extend their lists, are essential for this kind of birdwatcher. When I watched birds with a greater seriousness than I do now I definitely fell into the first camp.

I suppose that accounts for the way I choose to make photographs, also tramping over the same ground at different times of day, in different seasons, taking pleasure in picking out something new from a piece of countryside or village that I've walked many times before yet never noticed. Making the occasional foray farther afield is part of my practice too. However, I have never been tempted to pursue my hobby by driving off to "photographic" locations, to exotic countries, or to meetings of other photographers in photogenic places: what I disparagingly call the "Luminous Landscape" approach to photography. To me that's photography as consumption just as "twitching" is about birdwatching as consumption.

Today's photograph was gathered during a circular walk I've undertaken many times. On this occasion I noticed that alongside some streams the leaves of the dead reeds had been fixed in a horizontal position, presumably by the effect of the wind. The way the late afternoon light was falling made them into an attractive subject, contrasting with the thin upright lines of their stalks. This shot has been converted to black and white using the digital equivalent of an orange filter which has increased the contrast of the image.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 132mm (264mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/200

ISO: 400

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

birdwatching,

black and white,

leaves,

photography,

reeds,

stalks

Tuesday, January 13, 2009

The first snowdrops

.jpg) click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeAs a child I always looked for the first snowdrops that make an appearance in early January, and I continue to do so as an adult. When I was younger the small white flowers signified the first noticeable appearance of new life in the new year. I now know that other plants such as winter flowering heather and winter jasmine produce flowers before the snowdrops open their petals, but I still see them as the first step in the long march out of winter into spring. To a child the name is appealing and prompts the comparison of the crowded banks of flower heads with the way large flakes settle on the grass at the beginning of a fall of snow. To my adult mind the English name is so much more decorative, descriptive and appealing than the Latin Galanthus nivalis.

The first snowdrops have appeared in my part of the world, next to the foundations of a sheltered old house wall where they grew last year, perhaps benefiting from the leakage of warmth into the nearby soil. In a couple of weeks large drifts of the flowers will fleck garden borders, the churchyard, the sparse grass under the trees, and the banks of the stream that meanders through the village, giving me the opportunity for a wide-angle, contextual photograph. In the meantime here's a hand-held close-up of some of the "early birds."

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 35mm macro (70mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f11

Shutter Speed: 1/30 seconds

ISO: 200

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

bulbs,

flowers,

Galanthus nivalis,

snowdrop,

winter flowering

Monday, January 12, 2009

Anglesey Abbey

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeAnglesey Abbey, a country house near the village of Lode, Cambridgeshire, is now in the care of the National Trust. Much of the building, the 98 acres of garden, and the nearby eighteenth century Lode Water Mill, are open to the public. The house, as its name suggests, began life as a religious foundation. During the reign of Henry 1, i.e. between 1100 and 1135, Augustinian monks built a priory here. It continued as a religious building until the expulsion of the monks during the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1535. Around 1600 it was taken into private ownership and converted into a house. The ruinous remains were extended and improved in subsequent centuries, taking on the appearance of a building of the C17 and C18 with earlier remains. In 1973, on the death of the owner, the building and gardens were left to the National Trust.

The great temptation with a subject such as this is to fill the frame with a main facade or perhaps a corner, giving emphasis to one side of the building, letting the light model the walls, window bays, doorways, roofs and chimneys. On my visit I took some shots that did this. However, an image that gives a house context is also desirable, particularly one such as this where the setting, surrounded by trees, lawns and gardens, is central to the way its owners conceived the building. On the day I was there the sky was flawless blue, so this composition that minimised the overarching blandness, and offered a glimpse of the main facade across lawns from behind trees and shrubs, seemed a good approach. The dappled shadows of trees behind me gave foreground interest on a clear, cold, winter day.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 21mm (42mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/500

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

Anglesey Abbey,

Cambridgeshire,

composition,

country house

Saturday, January 10, 2009

Photographic effects and silver birches

click photos to enlarge

click photos to enlarge

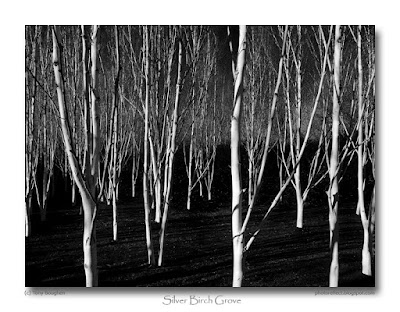

There's a saying amongst some photographers that an effect applied after shooting won't make a bad photograph into a good one. It's a maxim born of seeing too many images where HDR, selective colouring, starbursts, graduated colours and the like, are added for just that reason. Some purists go further and see any effect as an unwelcome addition, regardless of the quality of the original. I think that the originally stated case is largely true, but as for the idea that effects have no place in photography, well, I disagree. The fact is there are too many good photographers who prove the contrary.

Bill Brandt, the British photographer, is probably best known for those images to which he applied the effect of very high contrast. The U.S.-born Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzsky 1890-1976) was so fascinated with photographic manipulation that a significant part of his ouvre uses his "rayograph" technique or solarization. Other examples of the use of effects can be found in the work of eminent photographers past and present.

So, why are effects not widely used? Well, it depends on what you're trying to achieve with your images. Brandt is also known for his "documentary" style photographs of the working class in England's northern cities. In those images he mainly used traditionally exposed black and white photography of "normal" dynamic range. But, he's also known for pictures that lean towards the artistic side of photography, and here is where he uses high contrast - almost pure black and pure white in some instances. Man Ray come from the tradition of Dada, and painted as well as taking photographs. Consequently his portraits of notable people tend to be recognisably "normal" photographs, whereas his artistic abstracts use more unusual effects. Both photographers used effects where it contributed to what they wanted to achieve.

There is clearly a place for effects, though I tend to agree that over-use soon becomes tiresome, and makes you wonder why photography is the chosen medium as opposed to painting. I don't use such effects too often, but sometimes a subject tips me in that direction, as did this grove of bone-like silver birches. I've applied two effects to copies of the shot I took. I can't decide whether I prefer the "halo" effect" in colour, or the high contrast black and white. Each adds something to the original image that I find attractive. How about you?

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 11mm (22mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/320

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

Bill Brandt,

halo,

high contrast,

Man Ray,

photographic effects,

silver birch,

trees

Friday, January 09, 2009

Too near the sun

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeDaedalus was exiled to Crete because he gave Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos, the string that Theseus used to escape from the Labyrinth and the Minotaur. So, being a master craftsman, he came up with an escape plan that involved fashioning pairs of wings of wax and feathers for himself and his son, Icarus. However, the rashness of youth caused Icarus to spurn his father's advice and, flying too near to the sun, the wax melted causing the feathers to fall off the wings, and the rash boy to plunge to his death in the Mediterranean. In so doing he sparked a metaphor about "venturing too close to the sun" that has been pressed into service by writers down the ages.

I thought about this as I looked at my shot of some old sheds on Lincolnshire's flat Fenland landscape. An overnight frost and fog was being illuminated by the rising sun, and I tried to include some of the colours I could see being produced as the rays penetrated the cold air. However, I think I ventured too close to the sun and pink that I don't think figured in the colours of the sky, was introduced into the shot, perhaps by the light bouncing around the lens elements. However, I quite like the effect, and see it as an artifact of the photographic process akin to flare, noise or reduced dynamic range.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 40mm (80mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/200

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Thursday, January 08, 2009

Morris & Co

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeI spend my life ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich."

William Morris (1834-1896), English designer, artist, writer and socialist

If you fancy a bit of linen featuring an original William Morris print, or perhaps a rug or wallpaper with his distinctive patterns and colours, say, "Chrysanthemum Minor" or "The Strawberry Thief", Liberty's of London will be delighted to sell it to you. So too will a number of up-market stores throughout Britain, because Morris' designs are still sought after by the discerning (and well-heeled). Should you doubt that the copies you have purchased are faithfully modelled on the originals you can pop into the Victoria & Albert Museum and view examples from the time of first manufacture, or look at The Green Dining Room (1866-68) that he fitted out for the museum. As the quote at the head of this piece suggests, Morris regretted that the art he created could only be afforded by people of means. His designs that are sold today continue to be expensive unless you buy the coasters, mugs, bookmarks and the like, that have appropriated his patterns and displayed them in ways that he never intended.

However, if you don't live in London, there is a way to see some of Morris & Co.'s work without it costing the earth - visit a church. From 1861 Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co (called Morris & Co from 1875) designed stained glass for houses and churches right through until their demise in the 1930s. The quality of the firm's output in this field declined after the founder's death, and was at its peak when Edward Burne-Jones worked for the company. Though not the biggest supplier of coloured glass to churches Morris' firm was undoubtedly the best, and examples are not difficult to come by. I have posted one of my favourite pieces from Brampton in Cumbria previously, and today's example is also to be found that county, this time in the church of St Paul, Irton. It depicts St Agnes (with the lamb) and St Catherine of Alexandria. The figures are beautifully drawn by Burne Jones, unmistakably his work in the Pre-Raphaelite style, and, whilst not as delicately coloured as some of his windows, nonetheless they are a pleasure to look at and an example that surpasses most of the stained glass of that period.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 43mm (86mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.5

Shutter Speed: 1/40

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, January 07, 2009

The magic of snow

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlarge"snow (noun) - a precipitation in the form of ice crystals, mainly of intricately branched, hexagonal form and often agglomerated into snowflakes, formed directly from the freezing of the water vapour in the air."

Definition at Dictionary.com

The definition of snow quoted above might satisfy the meteorologists but it's no good for me. I know that it falls out of the sky like rain, but the fact is it's much more fun than rain. Snow flakes may be ice crystals but they rarely look like them. Moreover, I've seen the photographs of the hexagonal crystals, every one unique, that combine to form flakes, but I've never looked at snow and seen them with my own eyes. So, whilst I'm prepared to believe all that I'm told about snow by the scientists, I think their definition falls short unless they also admit that it's magical. Now I know that the Enlightenment banished magic and thrust science to the fore, and that no (or rather few) self-respecting modern scientists will admit a place for magic in their explanations of anything. Yet, snow hides its substance from us so well, and confers such a change on the world when it descends that it clearly is, if not magic, then certainly magical.

Perhaps I'd see snow differently if I lived in Canada or Siberia. But, living on a small island, in the path of the Gulf Stream, and subject to only the occasional fall of the white stuff, I have a liking for it. As a photographer I always want a few days of it each year for the transformational effect it has on familiar scenes. The recent extended cold spell that has gripped the UK has produced frosts a-plenty, and snow in several parts of our islands, but only a few desultory flurries in my area. Consequently, today's black and white photograph is one that I took last year. I post it in the hope that it might precipitate a decent "precipitation in the form of ice crystals...agglomerated into snowflakes" that will work its winter magic.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 12mm (24mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/200

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: +1.0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

Bicker,

black and white,

church,

churchyard,

Lincolnshire,

snow,

St Swithun

Tuesday, January 06, 2009

Navigation by tower and spire

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeAs I cycle across the Lincolnshire Fen landscape I feel like a mariner sailing through a familiar archipelago. The flatness of the land gives views of several miles in all directions, and standing up tall like lighthouses or rocky islands, are medieval churches, markers that allow travellers to plot and mark their course through the web of narrow lanes.

A large, distant clump of trees usually means a village. But, in this region of large churches a spire or a tower usually rises above the tallest beech or lime, and the traveller who can tell one from the other can have no doubt of their position. So, Heckington's high tower but short spire distinguishes it from nearby Helpringham's rocket-like pinnacles attached to a tall spire, and from Donington's which is set well within its tower-top perimeter. Gosberton's thin, attenuated, needle spire cannot be confused with Quadring's shorter spire and tapered tower, and Swineshead's short spire with its stone corona at the base is different again. Swaton's green roof and embattled tower is very different from nearby Bicker's lower tower that barely peeps over the nearby pines and beeches. Towards The Wash, Fosdyke's lead spire is whiter than Long Sutton's which has clasping leaded pinnacles, which is in turn completely unlike Holbeach's spire that rises from a tower.

So, a compass is an unneccesary luxury in the Fens unless, of course, a mist or fog descends. Then, especially at the end of the day, the towers and spires take on a ghostly quality, near buildings look more distant, and churches can be appreciated solely for the beauty and individuality of their outlines, as in the photograph above of Swineshead.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 150mm (300mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/400

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

church,

Lincolnshire,

navigation,

silhouette,

spire,

Swineshead,

tower

Monday, January 05, 2009

Egyptian Revival

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlarge"I don't care to belong to any club that will have me as a member."

Groucho Marx (1890-1977), U.S. comedian and actor

Many years ago I received an unsolicited invitation to join a society. It was the sort of organisation that only admits those who are nominated by existing members. I declined the offer, not for Groucho's reason (though I have some sympathy with his thinking), but because I find the idea of an organisation of people that only admits those whom they choose, rather than anyone who meets a published list of entry criteria, distasteful. I know I'm not alone in this way of thinking. However, I'm equally sure that there are many who are flattered by such an approach, and who relish the thought of becoming part of what they see as an elite or select group. Such organisations have existed for hundreds of years, and usually have an economic, social or "learned" basis. In my view they have no part in a modern society; not because of what they are or what they do, but because of the way they are constituted.

These thoughts came to mind as I walked down a fairly ordinary street in Boston, Lincolnshire, all red brick, bay windows and white paintwork, and was hit in the eye by this essay in Victorian Egyptian Revival. It was built for the Freemasons, by the architect George Hackford, between 1860 and 1863. I know nothing about this organisation except that it has obscure beginnings, may have grown out of the medieval masons who built our churches and cathedrals, and continues to use some quite obscure symbols (I often come across the Masonic square and compasses on gravestones). The facade is based on the Temple of Dandour in Nubia, a building dating from about the time of Christ, that was given to the United States in the 1963 and now resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The 1860s is very late for an Egyptian Revival building in Britain: the period between Napoleon's excursions in Egypt and about 1845 is when most such structures were erected. Perhaps the Freemasons chose this style for its mystery and hieroglyphs. Or maybe it was the publicity given to this particular temple through paintings and prints in the 1840s, and a large photographic exhibition in the 1850s.

I took a few shots of the facade, but chose this one for two reasons. Firstly the two bright blue refuse bins flanking the base of the columns behind the pavement level railings added nothing to an overall composition, and secondly, this more dynamic perspective includes most of the architectural and decorative interest on offer.

Oh, and for anyone who's wondering, the organisation that approached me all those years ago wasn't the Freemasons, who, I read, are open to applications by prospective members.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 11mm (22mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/40

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, January 02, 2009

Winter photography

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeA spell of winter weather that is colder and duller than usual has kept people indoors recently. A quick skip round the photography forums finds many in the UK wishing for brighter skies. Like most photographers I relish bright, contrasty light. A sky with 70% broken cloud of different hues (the kind seen after rain), blue showing through here and there, and pools of sunlight reaching the ground, is probably my ideal for landscape shots.

But, different weather presents different opportunities and we must seize them. Heavy rain is pretty useless as far as I'm concerned, with only a few opportunities for images. Light rain or drizzle offers more chance of capturing glistening photographs. A leaden sky with a blanket of stratus above is lamented by many, but can be fine as long as you keep the camera pointed down, and, if it's bright enough, is particularly good for saturated colours and therefore plants and flowers. Snow is great, not only for the novelty (at least in much of England), but also because of the way it converts scenes into drawings with dark shapes and lines across a white surface, and for how it changes the light and illuminates the shadows. Fog is good too, and I often venture out in such weather to try and capture the graduated tones and simplified silhouettes it offers. That was my thinking the other day when we went for an afternoon walk near Swineshead in Lincolnshire. A weak sun was shining through wispy cloud and visibility was poor. It looked like mist and fog would start to appear as the sun went down. And so it did.

I took this photograph towards the end of the walk, balancing the faint outline of Swineshead church towering over the village houses, with the silhouettes of trees on the right, and used the curve of the road as a leading line into the shot.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 137mm (274mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/100

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Labels:

church,

fog,

Lincolnshire,

mist,

photography,

Swineshead,

weather

Thursday, January 01, 2009

Revisiting the OM1

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeToday's photograph was taken on 11th May 1986 during a visit I made to Southwell Minster, Nottinghamshire. It shows one of the remarkable carved capitals in the Chapter House, a part of the Minster built in the late 1200s as the Early English style of Gothic architecture was turning towards the Decorated.

The carved stonework of the Chapter House is some of the best to be found in Britain. It includes ten "green men", many label stop heads, a vaulted roof (the only example that isn't supported by a central pier), and numerous delicate capitals on slender columns. These beautifully sculpted pieces depict recognisable plants including the maple, oak, hawthorn, buttercup, potentilla, vine, ivy and hops. It's hard to imagine how the carvers went about creating such intricacy, and how the details have managed to survive relatively unscathed to the present day. The architectural historian, Nikolaus Pevsner, notes that the creators achieved a synthesis of nature and style, not merely copying the leaves, but depicting them in a way that doesn't deny the stone of which they are made. The result is very moving.

I include this photograph as an example of the output of my Olympus OM1n with the Zuiko 50mm 1.8 lens. I'd been using it for over 10 years when I took this shot. The image is also a testament to the durability of an image shot on Fujichrome transparency film. The colour and clarity are, as far as I can see, just as good today as when I made the original exposure. I hope that the digital files I now create will be in as good shape twenty two years hence. In theory they should be, but changes in file formats and operating systems, as well as the fallibility of storage devices leads me to think I could be disappointed. The slide was scanned using a negative and transparency holder on a new flatbed scanner that came my way at Christmas. The quality produced in what is essentially a light-box add-on to a fairly standard and inexpensive scanner has amazed me. It's at least as good, perhaps better than I can achieve with a dedicated film scanner that I bought six or so years ago, and has the advantage of copying multiple images in one pass. I intend to compare it with a digital enlargement of a slide photographed with the E510 using the 35mm macro lens. If the results are acceptable I'll post that shot too.

One of my more recent images of Southwell Minster can be seen here.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus OM1n

Mode: Manual

Focal Length: 50mm

F No: f4

Shutter Speed: 1/60

ISO: 100

Film: Fujichrome

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: N/A

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)