click photo to enlarge

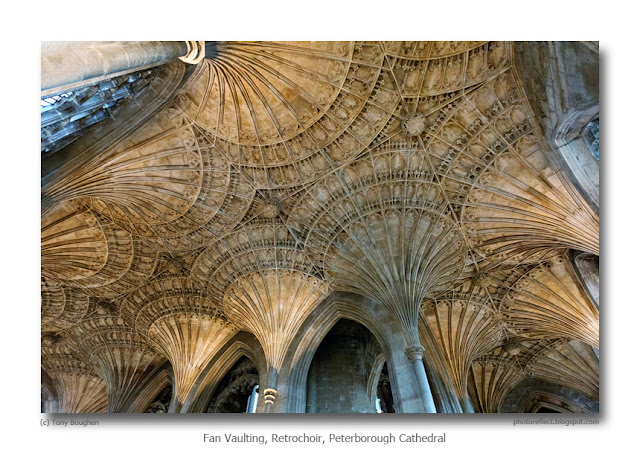

"Looking Up" was the title of a blog post that I made in May 2008 featuring the same subject as today's entry - the underside of the tower, together with the ceilings of the nave, chancel and transepts of Peterborough Cathedral. As part of my workout that aims to make me familiar with my new camera's strengths, weaknesses and peculiarities, I've been photographing a range of subjects, some that I've shot before, using different lenses, apertures, shutter speeds, ISOs and EV settings. This shot is with my unstabilized 17-40mm lens, and the shutter speed of 1/10 second is about the limit of what I can successfully hand-hold. Viewed at 100% this shot is pretty sharp. Of course, the ISO of 3200 is what makes the image possible. You might wonder why I didn't open the lens up, but I find that some corner softness appears at its maximum of f4. This isn't too much of a problem with, say, a landscape, but with the straight, sharp lines of architecture - even the several hundred years old variety - it can be noticeable.The centre of today's image shows the timber lierne vault on the underside of the central (crossing) tower of the cathedral. The other ceilings are also timber. This is not unusual with the wide spans of a Romanesque building of the twelfth century. The ability to throw stone vaulting over such a distance hadn't been developed at that time, though it was used in the narrow aisles here. The hierarchy of decoration that can be seen in the four main ceilings reflects the relative importance of each part of the cathedral. Thus, the painted, closely coffered ceiling, with decorative bosses, flanked by vaulted coving over the chancel (on the right), that dates from the fifteenth century, emphasises the liturgical centre of the church, the place where the clergy worked, and the location of the high altar. The painted nave roof with its elongated diamonds each with a central figure - kings, queens, saints, fantastic animals etc - dates from about 1220. Pevsner calls it "a precious survival". This is over the part of the church devoted to the laity. The other two ceilings that roof the transepts are also original, and though the wood is again laid in diamonds, it is not painted, and they are definitely subsidiary to the main two.

I often think that photographs of this subject, taken from directly below with symmetry, have something of the look of a kaleidoscope image, and this one is no exception. For more views of vaulting and the underside of towers see these photographs from Louth and Ludlow, Morton, Brant Broughton, Pershore, Boston, Norwich, and Ely.

photograph and text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 17mm

F No: 7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/10

ISO: 3200

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: N/A