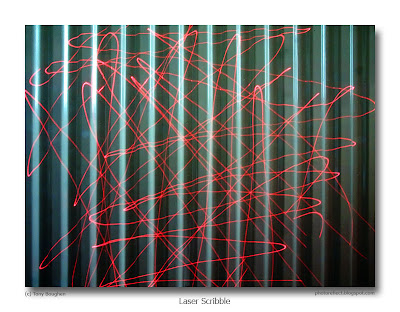

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeCan you make a worthwhile photograph when you're having a conversation with someone? Many portrait photographers would argue that talking to your subject is the best way to secure such an image. But, that specific genre aside, isn't it the case that you have to give all your attention to the creativity and technicalities of photography, and that talking about an entirely unrelated subject just gets in the way of making an image?

Yesterday I was sitting at my desk talking to a visiting family member when the conversation turned to London architecture and the new buildings I might like to see on my next visit. A laser pointer of the sort used with a digital projector came to hand and I began idly pointing it at the central heating radiator as I spoke. Moving it over the corrugated surface it occurred to me that it could make light trails in a photograph, similar to those made by firework "sparklers". So, without a break in the conversation I set up the tripod and camera - fortunately my visitor knew me well enough to think nothing of this - and took a few shots with the lens stopped right down to decrease the shutter speed.

The resulting image had a colour shift and a little flare due to the very long exposure. However, those things are of little consequence with the semi-abstract composition that I had in mind. I increased the contrast in processing to reveal the true colour of the laser light, which also had the effect of darkening the colour of the radiator. The final outcome is the image you see above. It isn't the greatest photograph I've ever made, but I like the colour combination, the "scribble" effect, and the random line overlaying the regularly spaced verticals. Reviewing the shot objectively I suppose the answer to my opening question is, "No." However, on the basis of this photograph I do think you can make an interesting image when you're chatting to someone. Incidentally, by the end of the conversation and image making I'd got a reasonable idea of the new buildings I might like to see on my next London trip.

photograph & text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Olympus E510

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 14mm (28mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f22

Shutter Speed: 10 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On