click photo to enlarge

Many years ago, when my children were young we were on a beach in Lancashire when a large dog came racing towards us, ignoring the shouted commands of its owner. It jumped up at my sons, towering over them, frightening them, almost knocking them down. That was one of the few occasions in my life I've come up with a retort that I couldn't improve on after the event. I said to the dog owner, as she ran up assuring us that it "only wanted to play", "There's nothing like a well-trained dog, and that's nothing like a well-trained dog." My observation-cum-complaint didn't go down well with the owner, but then that was my intention. I must surely have heard those words somewhere before, I can't imagine I thought them up myself. But they came out with perfect timing as though they were all mine.

I have nothing against dogs. We had them when I was a child and I enjoyed them. I've known and liked many dogs that are good-tempered and well-trained. But I've also come across plenty that are none of these things due to the improper care they receive, or the way they are used to protect property, especially if it's a farm through which a public footpath runs. For many years I thought I'd have a dog when I retired, but I've reached the conclusion that a dog would restrict what we do far too much, so I'm very likely to remain dogless.

The other week, when were on Skegness beach, that episode with my children and the dog came to mind once more. It often does when we see dog walkers on a beach. I well understand the desire of owners to let their dogs run free in the wide open space because the animals visibly enjoy the experience. I just wish those who have no control over their dogs wouldn't do so. However, I'm pleased to say that those providing the human and doggy interest in today's photograph were impeccably behaved.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 31.8mm (86mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/800 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Pages

▼

Friday, January 31, 2014

Wednesday, January 29, 2014

Rain over the Humber Bridge

click photo to enlarge

How long does it take to judge the quality of a photograph? I'm thinking more about the "keepers", not the ones I cull immediately. How long is it before I consider them to be one of my better efforts or one of the much larger, "O.K" group? You might think that an odd question since quality must always shine through. However, I think that most people can more quickly judge quality in other photographers' images than their own. Photographs that you and I make carry more information and have more invested in them by us, than do those made by strangers. We know the circumstances in which we make our own photographs, where the image stands alongside other versions of the same shot, any difficulties overcome in securing it, etc. In other words we don't always judge it solely on its photographic merit, whereas that is something we can much more easily do with the work of a stranger.

So, how long does it take to judge the quality of a photograph? For me, I know that if I live with it for a couple of weeks I've usually come to a settled opinion as to its worth. That is the point at which I confirm a judgement made earlier, whether good or bad, or more often, slightly shift one way or the other from my initial thoughts, making a promotion or demotion if you will. Of course, when you run a blog that has the self-imposed task of showing a new photograph every other day, then sometimes you run low on images, and the luxury of considering one for a fortnight becomes impossible. Today's photograph is a case in point. It was taken on Sunday, was one of only three shots taken on the day (yesterday's post shows another), and I haven't really made my mind up about it. One thing I do like, that probably tipped me into using it before some other, older photographs, is the way it conveys a certain type of wet, English winter day, with its leaden sky and reduced visibility. The other thing that appealed to me was the contrast of the brown and greens of the grass and reeds with the monochrome sky, river, bridge and trees.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 18.2mm (49mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/250 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

How long does it take to judge the quality of a photograph? I'm thinking more about the "keepers", not the ones I cull immediately. How long is it before I consider them to be one of my better efforts or one of the much larger, "O.K" group? You might think that an odd question since quality must always shine through. However, I think that most people can more quickly judge quality in other photographers' images than their own. Photographs that you and I make carry more information and have more invested in them by us, than do those made by strangers. We know the circumstances in which we make our own photographs, where the image stands alongside other versions of the same shot, any difficulties overcome in securing it, etc. In other words we don't always judge it solely on its photographic merit, whereas that is something we can much more easily do with the work of a stranger.

So, how long does it take to judge the quality of a photograph? For me, I know that if I live with it for a couple of weeks I've usually come to a settled opinion as to its worth. That is the point at which I confirm a judgement made earlier, whether good or bad, or more often, slightly shift one way or the other from my initial thoughts, making a promotion or demotion if you will. Of course, when you run a blog that has the self-imposed task of showing a new photograph every other day, then sometimes you run low on images, and the luxury of considering one for a fortnight becomes impossible. Today's photograph is a case in point. It was taken on Sunday, was one of only three shots taken on the day (yesterday's post shows another), and I haven't really made my mind up about it. One thing I do like, that probably tipped me into using it before some other, older photographs, is the way it conveys a certain type of wet, English winter day, with its leaden sky and reduced visibility. The other thing that appealed to me was the contrast of the brown and greens of the grass and reeds with the monochrome sky, river, bridge and trees.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 18.2mm (49mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/250 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Monday, January 27, 2014

Rainy days

click photo to enlarge

There are a number of reasons why I moved to eastern England. One of them is to experience the drier weather. I was born and raised in north-west England, a part of the country known for its regular and relatively high rainfall. I lived in Hull for a number of years and experienced there something of the drier weather that side of the country offers. But then I moved back to west Lancashire for about twenty years, once again subjecting myself to the wetness of the west. Now, however, living in Lincolnshire, I find that my love of the great outdoors is more easily sated and need not incur the drenchings that accompanied more than a few forays in the west. Moreover, I can usually plan to do something outdoors without needing to calculate whether or not it will be rained off - because it usually isn't.

Consequently, the recent days, most of which seem to have included a spell of rain at some point or another, have been something of a let-down. I've come to expect better! Or at least, different. It even poured down for much of our regular monthly trip north, over the Humber Bridge, into Yorkshire. So, with the expectation that I couldn't insert any photography based detours into our itinerary, we decided to do the weekly shopping a little earlier than was required, thereby making the most of the day that way instead. Today's photograph was taken after we'd parked in the supermarket car park, just before we scurried into the dry in search of groceries. The darkness of the afternoon, the rain-spattered windscreen,the glistening cars and tarmac, and the early lights necessitated by the murk of the day, offered one of only three photographs I took on the whole outing. Not my greatest shot, but not without some interest I think.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 15.3mm (41mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/50 sec

ISO:800

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

There are a number of reasons why I moved to eastern England. One of them is to experience the drier weather. I was born and raised in north-west England, a part of the country known for its regular and relatively high rainfall. I lived in Hull for a number of years and experienced there something of the drier weather that side of the country offers. But then I moved back to west Lancashire for about twenty years, once again subjecting myself to the wetness of the west. Now, however, living in Lincolnshire, I find that my love of the great outdoors is more easily sated and need not incur the drenchings that accompanied more than a few forays in the west. Moreover, I can usually plan to do something outdoors without needing to calculate whether or not it will be rained off - because it usually isn't.

Consequently, the recent days, most of which seem to have included a spell of rain at some point or another, have been something of a let-down. I've come to expect better! Or at least, different. It even poured down for much of our regular monthly trip north, over the Humber Bridge, into Yorkshire. So, with the expectation that I couldn't insert any photography based detours into our itinerary, we decided to do the weekly shopping a little earlier than was required, thereby making the most of the day that way instead. Today's photograph was taken after we'd parked in the supermarket car park, just before we scurried into the dry in search of groceries. The darkness of the afternoon, the rain-spattered windscreen,the glistening cars and tarmac, and the early lights necessitated by the murk of the day, offered one of only three photographs I took on the whole outing. Not my greatest shot, but not without some interest I think.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 15.3mm (41mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/50 sec

ISO:800

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Saturday, January 25, 2014

Art Deco and the Adelphi

Between the years of 1768 and 1772 the architect brothers, Robert and James Adam, built a group of Thames-side streets and grand terraces called the Adelphi. The name is very appropriate, coming from the Greek, "adelphoi", meaning brothers. The project was on a grand scale. It involved embanking the river, demolishing and removing the remains of Durham House, then building their new scheme using large amounts of their own money. The undertaking nearly bankrupted them and a lottery was needed to get them out of their financial predicament. The most striking part of the Adelphi was the riverside terrace. It stood on arched vaults and was composed in what was by then a common style - with emphasised centre and "pavilion" ends - making the whole appear rather like one majestic building or a transplanted country house. However, unlike most examples the centre and terrace ends barely projected, very shallow pilasters doing the job instead. It was rather like the Adam brothers had transplanted their interior decoration to the main elevation.

The Adelphi was demolished in the 1930s to make way for the enormous Art Deco buildings that now stand on the site of the brothers' imaginative scheme. Today's photograph shows the main pair - the Adelphi Building and Shell Mex House. Despite the great numbers of Art Deco (formerly more commonly known as Moderne) buildings that were constructed the history of twentieth century architecture sees the style as something of a disappointing dead-end. It doesn't fit neatly into the line that stretches from Gropius, through Mies and Le Corbusier, to Philip Johnson, S.O.M., Foster, Stirling, Rogers and the rest. Rather than the break with the past that these architects represent, Art Deco is seen as a continuation of classicism, an updating of it certainly, but tradition dressed in modified clothing nonetheless.

There is some truth in that point of view, but it shouldn't blind us to the decorative style and exuberance that Art Deco often displays, or to the monumentality that sometimes sits quite well alongside older buildings in a city. When I stood on the South Bank to take this photograph across the Thames I reflected that the simple, gigantic clock on Shell Mex House could belong to no other time than the 1930s, and the uplighting of both buildings seemed to work so well with their windows and their stepped back floors.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 28.2mm (76mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5

Shutter Speed: 1/80 sec

ISO:800

Exposure Compensation: -1.0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Thursday, January 23, 2014

Industrial semi-abstract with reflections

click photo to enlarge

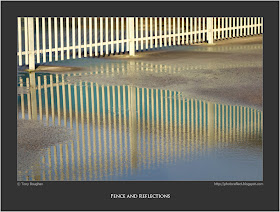

The word "industrial" in the title of today's blog post is something of a misnomer. The fact is that Lincolnshire, with a few exceptions doesn't feature much of what is usually called industry. It is a predominantly rural and coastal county with no large cities, and few areas of heavy industry - steel making at Scunthorpe and petro-chemical processing near Grimsby is about it. However, it is an agricultural county with a greater proportion of the workforce engaged in growing, processing or packing produce of one sort or another than is to be found in most counties. Consequently there are quite a few sites in the countryside or adjoining villages and towns, that have some of the characteristics of industrial buildings. Large, anonymous steel sheds are commonplace, as are strong perimeter fences.

The other day we walked past such a place, one that from the signs on the building appears to be engaged in distributing flowers. The heavy rain of morning had been followed by afternoon sunshine and its car park was awash with large puddles reflecting the "palisade" security fencing with its viciously pointed tops. The colours, lines, irregular patches of water and tarmac, and the reflected building and sky made an interesting abstract composition. I homed in on a section that seemed to offer something of interest across the viewfinder and took this shot. I used to do more semi-abstract compositions when I lived in a more urban area. I think it's something that I'll have to get back into.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 37.1mm (100mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f6.3

Shutter Speed: 1/200 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

The word "industrial" in the title of today's blog post is something of a misnomer. The fact is that Lincolnshire, with a few exceptions doesn't feature much of what is usually called industry. It is a predominantly rural and coastal county with no large cities, and few areas of heavy industry - steel making at Scunthorpe and petro-chemical processing near Grimsby is about it. However, it is an agricultural county with a greater proportion of the workforce engaged in growing, processing or packing produce of one sort or another than is to be found in most counties. Consequently there are quite a few sites in the countryside or adjoining villages and towns, that have some of the characteristics of industrial buildings. Large, anonymous steel sheds are commonplace, as are strong perimeter fences.

The other day we walked past such a place, one that from the signs on the building appears to be engaged in distributing flowers. The heavy rain of morning had been followed by afternoon sunshine and its car park was awash with large puddles reflecting the "palisade" security fencing with its viciously pointed tops. The colours, lines, irregular patches of water and tarmac, and the reflected building and sky made an interesting abstract composition. I homed in on a section that seemed to offer something of interest across the viewfinder and took this shot. I used to do more semi-abstract compositions when I lived in a more urban area. I think it's something that I'll have to get back into.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 37.1mm (100mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f6.3

Shutter Speed: 1/200 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Tuesday, January 21, 2014

A touch of strong colour

click photo to enlarge

Ever since mankind has created pictures colour has been a key element of the armoury of the artist. Colour is powerful, seductive, noticeable and descriptive. But, as photographers who favour black and white often claim, it can overwhelm an image, introduce a note or mood the artist doesn't require, or detract from the essence of what is offered. Consequently, artists have often sought to use colour sparingly, recognising as cooks do with their herbs and spices, that a little can go a long way. Since the rise of colour photography that has been one of the approaches that photographers have adopted too.

Several years ago, when I was more involved than I am today with the wider photographic community, I acquired a reputation for photographs that included a strong but small note of vivid colour (often red) in an otherwise relatively muted colour palette. In fact, my second post on PhotoReflect, way back on 24th December 2005, "The Power of Colour" both exemplifies and discusses that approach to composition. I continue to periodically produce photographs with that characteristic, such as this photograph of a ladybird or this one of a snagged red net bag by the sea.

One recent morning, on a shopping trip to Sleaford, Lincolnshire, I had the opportunity to add another such image to my collection. By a small pond, at the end of a wooden walkway that stretched from the path to a small fishing jetty, was a bright orange life belt. The overnight frost had laid a veneer of white over timber and vegetation, reducing the impact of these colours and emphasising the vivid orange circle. Holding my camera above my head to make more of the timber path and rails as a line into the composition I took the photograph that I offer today.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/40 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Ever since mankind has created pictures colour has been a key element of the armoury of the artist. Colour is powerful, seductive, noticeable and descriptive. But, as photographers who favour black and white often claim, it can overwhelm an image, introduce a note or mood the artist doesn't require, or detract from the essence of what is offered. Consequently, artists have often sought to use colour sparingly, recognising as cooks do with their herbs and spices, that a little can go a long way. Since the rise of colour photography that has been one of the approaches that photographers have adopted too.

Several years ago, when I was more involved than I am today with the wider photographic community, I acquired a reputation for photographs that included a strong but small note of vivid colour (often red) in an otherwise relatively muted colour palette. In fact, my second post on PhotoReflect, way back on 24th December 2005, "The Power of Colour" both exemplifies and discusses that approach to composition. I continue to periodically produce photographs with that characteristic, such as this photograph of a ladybird or this one of a snagged red net bag by the sea.

One recent morning, on a shopping trip to Sleaford, Lincolnshire, I had the opportunity to add another such image to my collection. By a small pond, at the end of a wooden walkway that stretched from the path to a small fishing jetty, was a bright orange life belt. The overnight frost had laid a veneer of white over timber and vegetation, reducing the impact of these colours and emphasising the vivid orange circle. Holding my camera above my head to make more of the timber path and rails as a line into the composition I took the photograph that I offer today.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/40 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Sunday, January 19, 2014

A London street in Lincolnshire

click photo to enlarge

Tucked away in an area of woodland in Kew Gardens there is a timber-framed brick cottage with a thatched roof. It was originally single storey but later had an upper floor added. It was built between 1754 and 1771 for Queen Charlotte, a cottage orné to serve as a destination for her rural walks, a place to rest and take tea; to experience what she imagined to be the bucolic lifestyle of a yeoman farmer without getting her hands dirty. The desire to build in old styles was a notable feature of the Georgian period. Alongside the styles that they invented they also built using features of Greek and Roman architecture, invented a style of Gothic architecture sufficiently different, yet like the original that it came to be called "Gothick".

The Victorians continued this trend emulating the Italianate villas of the Mediterranean in their suburban detached and semi-detached housing, and at the most extreme borrowing details from Egyptian, Saracenic and Indian architecture. They too plundered Gothic with abandon. However, like the Georgians they built much that owed little or nothing to past styles. And, unlike the Georgians they built it virtually anywhere, too often heedless of vernacular and local traditions. The twentieth century followed suit with, for example, watered down European "Moderne" influencing suburban houses of the 1930s, Georgian columns and bulls-eye windows favoured in the 1970s and Victorian tile-hanging, plinths, roof cresting and fake half-timbering being popular in the 1990s. The same style of house appeared on estates and streets the length and breadth of the country.

I was reflecting on this the other day when I was looking at Barkham Street in Wainfleet All Saints, Lincolnshire. The centre of this small country town is filled with modest brick buildings of the Georgian and Victorian periods, usually two storey, often with the door opening on to the pavement. Consequently to turn a corner and see a London street plonked down amongst the unassuming Lincolnshire housing is something of a surprise. And it is a London Street too. A plaque on the buildings notes: "Barkham Street. Built in 1847 for Bethlem Hospital according to the design of Sydney Smirke, their architect, and named after their benefactor. A number of similar terraces stood in Southwark near Bethlem hospital." Smirke is best known as the architect of the circular Reading Room of the British Museum. Both sides of his street have the same rather grand elevations with the main living storey slightly elevated by a basement and emphasised by steps to the front door and stone framed windows. The relative importance of the two floors above is signified by differing window treatments. The houses make a fine sight, though a very unusual one for this locality.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 14.1mm (38mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/50 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Tucked away in an area of woodland in Kew Gardens there is a timber-framed brick cottage with a thatched roof. It was originally single storey but later had an upper floor added. It was built between 1754 and 1771 for Queen Charlotte, a cottage orné to serve as a destination for her rural walks, a place to rest and take tea; to experience what she imagined to be the bucolic lifestyle of a yeoman farmer without getting her hands dirty. The desire to build in old styles was a notable feature of the Georgian period. Alongside the styles that they invented they also built using features of Greek and Roman architecture, invented a style of Gothic architecture sufficiently different, yet like the original that it came to be called "Gothick".

The Victorians continued this trend emulating the Italianate villas of the Mediterranean in their suburban detached and semi-detached housing, and at the most extreme borrowing details from Egyptian, Saracenic and Indian architecture. They too plundered Gothic with abandon. However, like the Georgians they built much that owed little or nothing to past styles. And, unlike the Georgians they built it virtually anywhere, too often heedless of vernacular and local traditions. The twentieth century followed suit with, for example, watered down European "Moderne" influencing suburban houses of the 1930s, Georgian columns and bulls-eye windows favoured in the 1970s and Victorian tile-hanging, plinths, roof cresting and fake half-timbering being popular in the 1990s. The same style of house appeared on estates and streets the length and breadth of the country.

I was reflecting on this the other day when I was looking at Barkham Street in Wainfleet All Saints, Lincolnshire. The centre of this small country town is filled with modest brick buildings of the Georgian and Victorian periods, usually two storey, often with the door opening on to the pavement. Consequently to turn a corner and see a London street plonked down amongst the unassuming Lincolnshire housing is something of a surprise. And it is a London Street too. A plaque on the buildings notes: "Barkham Street. Built in 1847 for Bethlem Hospital according to the design of Sydney Smirke, their architect, and named after their benefactor. A number of similar terraces stood in Southwark near Bethlem hospital." Smirke is best known as the architect of the circular Reading Room of the British Museum. Both sides of his street have the same rather grand elevations with the main living storey slightly elevated by a basement and emphasised by steps to the front door and stone framed windows. The relative importance of the two floors above is signified by differing window treatments. The houses make a fine sight, though a very unusual one for this locality.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 14.1mm (38mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/50 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, January 17, 2014

Photographing the ordinary and familiar

click photo to enlarge

Every now and then I include a quotation in my blog posts. I like quotations for the way they frequently condense, pithily, an important truth in a small number of words. Several years ago, when moving house prevented me from maintaining PhotoReflect at its then current level, I created for a few months, a less labour intensive blog that I called PhotoQuoto. It gave me the opportunity to make use of some of the quotations I'd collected and savoured down the years and it was an exercise that I thoroughly enjoyed.

Recently, one of my blog posts from the first month of PhotoReflect's existence (January 18th 2006), as well as its attendant quotation, came to mind. We were doing a familiar walk past a collection of rather ordinary old barns. These seem to have grown up organically as needed, the oldest nearest the road, newer ones added on ever further away. Next to what was probably the oldest structure a relatively young ash tree stood, its "keys" still hanging in heavy bunches despite the weeks of strong winds that we experienced at the turn of the year. The buildings and tree, together with the puddles from recent rain, and the sky that looked like it might clear or could bring further precipitation, was suddenly enlivened by a fleeting glimmer of brighter light. The words that came to mind as I framed my shot were those that I'd used eight years ago, from the American director, artist and writer, Aaron Rose (1969 - ): "In the right light, at the right time, everything is extraordinary." In those few moments the familiar, mundane buildings came alive, photographically speaking, and seemed a much better prospect for a photograph than they usually do. Looking at the shot a couple of days later I still hold that opinion. However, I do wonder whether a photograph of some barns that I took last year might also have been a factor in making me look anew at this group.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/125 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Every now and then I include a quotation in my blog posts. I like quotations for the way they frequently condense, pithily, an important truth in a small number of words. Several years ago, when moving house prevented me from maintaining PhotoReflect at its then current level, I created for a few months, a less labour intensive blog that I called PhotoQuoto. It gave me the opportunity to make use of some of the quotations I'd collected and savoured down the years and it was an exercise that I thoroughly enjoyed.

Recently, one of my blog posts from the first month of PhotoReflect's existence (January 18th 2006), as well as its attendant quotation, came to mind. We were doing a familiar walk past a collection of rather ordinary old barns. These seem to have grown up organically as needed, the oldest nearest the road, newer ones added on ever further away. Next to what was probably the oldest structure a relatively young ash tree stood, its "keys" still hanging in heavy bunches despite the weeks of strong winds that we experienced at the turn of the year. The buildings and tree, together with the puddles from recent rain, and the sky that looked like it might clear or could bring further precipitation, was suddenly enlivened by a fleeting glimmer of brighter light. The words that came to mind as I framed my shot were those that I'd used eight years ago, from the American director, artist and writer, Aaron Rose (1969 - ): "In the right light, at the right time, everything is extraordinary." In those few moments the familiar, mundane buildings came alive, photographically speaking, and seemed a much better prospect for a photograph than they usually do. Looking at the shot a couple of days later I still hold that opinion. However, I do wonder whether a photograph of some barns that I took last year might also have been a factor in making me look anew at this group.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/125 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, January 15, 2014

Yellow-tinged January light

The light from the low winter sun has to travel obliquely through more of the earth's atmosphere than does the light from the higher sun of spring, summer and autumn. Consequently it is tinged with colour for the same reason that light from the rising or setting sun is coloured. In the second half of December and the first half of January the light of the middle of the day in Britain has a decided yellow cast. This colouration slowly retreats towards the beginning and end of the day as spring approaches. So, even if the appearance of the landscape doesn't betray the month the quality of the light in a photograph often shows that it was taken during that time of year when the hours of daylight are at their shortest.

We had a walk by the River Slea near South Kyme a few days ago. Here the slow flowing river meanders through flat farmland and small woods, past villages and their churches, and offers the photographer the element of water to add to the ever-present earth and sky. We've done that walk in winter a few times in recent years and I've photographed the medieval tower and church in their riverside locations before. On our recent walk I took a shot from a position where I remembered taking one previously. This time it was not only the yellow-tinged light that attracted my eye but also the dark clouds behind the sunlit river, fields and church. For the same reason I took a photograph of the nearby manor house, a building that has been added to over the centuries and is built of both stone and brick. Surrounded by its trees it makes the third of three very English buildings - a fortified tower/house, a small church fabricated from the aisle of a larger priory demolished during the Dissolution, and the manor house of the local worthy, a land and property owner who wielded power and influence in the locality. Today all the buildings are less than they were in terms of their position in their communities. The church has been in decline for a couple of hundred years, Kyme Tower fell out of use centuries ago, and manor houses and manorial rights are often not in the hands of the original family, where they exist at all.

Many enthusiast photographers reduce their picture taking in winter. Partly it's the inclement, cold, wet and windy weather that keeps them indoors. Others seem to prefer the photographic feel and appearance of the other three seasons. Then there are those who don't like the reduced light. I'm not one of those people. I've said elsewhere in this blog that I can't envisage living anywhere that doesn't have clearly differentiated seasons. Perhaps it's simply what I'm used to and I would get used used to permanent summer. However, the differences that seasons offer me as a person and a photographer are something that I would surely miss and would, perhaps, pleasantly surprise those who use their camera where the sun always shines.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 17.4mm (47mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/640 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Monday, January 13, 2014

Snapshots, dog walkers and wind turbines

click photo to enlarge

The words "snapshot" and "snap" in connection with photography seem to have pretty much disappeared from use by all but people over the age of, say, fifty. That's a pity because the first word very well describes the act of quickly seeing and taking a photograph without indulging in the lengthy consideration that might be taken with, for example, a landscape. It is a very appropriate word for the sort of shot that is frequently used in street, wildlife or sport photography. "Snap" for a routine or quickly taken photograph is also a useful term. In these days of smart phone cameras and the impromptu shots that they are often employed for, one wonders why the word isn't more widely used.

Snapshot, snapshooting and snaps came to photography from the world of shooting with firearms - rifles, shotguns and pistols. Quickly taken shots at game, targets or even people, were so described in the Victorian era, and are often still described with these words. I'm not the sort of photographer whose output relies heavily on snapshots but I do take photographs rapidly when I want to include people (those who are unknown to me) in my photographs because I usually have a very clear idea where I want them to be in the overall composition. Moreover, for reasons lost in the mists of time, all my digital photographs are in folders that are described with the word "Snaps" followed by the year.

The other day, when walking over the sand and dunes towards the sea at Skegness in Lincolnshire I took a snapshot. A dog walker appeared on a low dune ahead of us. He was silhouetted against the sky, with the sea and wind turbines behind him and a large pool in the foreground. I knew that he would soon be less visible against the sky so I started firing off a series of snapshots having first decided that I wanted a vertical composition with the main interest towards the top of the frame. Today's photograph is the second of four snaps that I took and it came out rather better than I imagined it would. That's another interesting thing about snapshooting: because it's quick you have hits and misses, and the hits, because they are not arranged to the last detail, have a surprise element that often makes them more rewarding than shots where everything turns out as planned.

Incidentally, I often wonder what I'd do without the scale and human interest that dog walkers offer when I'm photographing in the open spaces beside water or on sea-shore grass and dunes.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 37.1mm (100mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/1000 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

The words "snapshot" and "snap" in connection with photography seem to have pretty much disappeared from use by all but people over the age of, say, fifty. That's a pity because the first word very well describes the act of quickly seeing and taking a photograph without indulging in the lengthy consideration that might be taken with, for example, a landscape. It is a very appropriate word for the sort of shot that is frequently used in street, wildlife or sport photography. "Snap" for a routine or quickly taken photograph is also a useful term. In these days of smart phone cameras and the impromptu shots that they are often employed for, one wonders why the word isn't more widely used.

Snapshot, snapshooting and snaps came to photography from the world of shooting with firearms - rifles, shotguns and pistols. Quickly taken shots at game, targets or even people, were so described in the Victorian era, and are often still described with these words. I'm not the sort of photographer whose output relies heavily on snapshots but I do take photographs rapidly when I want to include people (those who are unknown to me) in my photographs because I usually have a very clear idea where I want them to be in the overall composition. Moreover, for reasons lost in the mists of time, all my digital photographs are in folders that are described with the word "Snaps" followed by the year.

The other day, when walking over the sand and dunes towards the sea at Skegness in Lincolnshire I took a snapshot. A dog walker appeared on a low dune ahead of us. He was silhouetted against the sky, with the sea and wind turbines behind him and a large pool in the foreground. I knew that he would soon be less visible against the sky so I started firing off a series of snapshots having first decided that I wanted a vertical composition with the main interest towards the top of the frame. Today's photograph is the second of four snaps that I took and it came out rather better than I imagined it would. That's another interesting thing about snapshooting: because it's quick you have hits and misses, and the hits, because they are not arranged to the last detail, have a surprise element that often makes them more rewarding than shots where everything turns out as planned.

Incidentally, I often wonder what I'd do without the scale and human interest that dog walkers offer when I'm photographing in the open spaces beside water or on sea-shore grass and dunes.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 37.1mm (100mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/1000 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Saturday, January 11, 2014

Tessellation

click photo to enlarge

Language is full of connections, which, if you make them, increases your understanding and use of language, but also expands your enjoyment of it too. Many years ago, when I was studying an aspect of mathematics, I was introduced to the word "tessellation" and the essential concepts that underpin it. At a basic level this involves the tiling of a flat surface with a finite number of geometric shapes such that there are no gaps or overlapping. The square tiles of a bathroom wall tessellate; so too do the hexagonal cells of honeycomb. However, as a branch of mathematics tessellation goes far beyond such simple examples. So too does tessellation in art. The Sumerians tessellated their clay tiles, as did the Islamic architects of the Alhambra in Spain; both used many different tessellating shapes. The Dutch graphic artist, M.C. Escher (1898-1972) famously created pictures with tessellating birds, dogs, lizards and all manner of other things.

When my lecturer used the word "tessellation" it immediately occurred to me that I'd already come across "tessellated" in school geography in connection with a feature in sedimentary rock known as a tessellated pavement, whereby erosion produces the effect of a layer of interlocking tiles. The word "tessera" also popped into my mind. This is the name for the individual pieces of a mosaic such as the Romans used for villa floors or the Byzantines used in their wall mosaics of religious and other subjects. It hadn't occurred to me before, but tessera means tile, more specifically, a 4-sided shape, and its meaning had been extended to describe all close-fit tiling of whatever shape.

On our most recent visit to London we came across a relatively new building near the Thames Cable Car. Ravensbourne College is the work of the Foreign Office Architects and, unusually in a modern British building, it has exterior walls that are tessellated with pentagons and triangles. Interestingly that's not necessarily what the first-time viewer notices because its other distinguishing feature is that every window above the ground floor level is circular! The building is certainly eye-catching. It is located next to the enormous and distinctive O2 (formerly known as the Millennium Dome) so one can understand the architects wanting it to claim its space.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 37.1mm (100mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/200 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Language is full of connections, which, if you make them, increases your understanding and use of language, but also expands your enjoyment of it too. Many years ago, when I was studying an aspect of mathematics, I was introduced to the word "tessellation" and the essential concepts that underpin it. At a basic level this involves the tiling of a flat surface with a finite number of geometric shapes such that there are no gaps or overlapping. The square tiles of a bathroom wall tessellate; so too do the hexagonal cells of honeycomb. However, as a branch of mathematics tessellation goes far beyond such simple examples. So too does tessellation in art. The Sumerians tessellated their clay tiles, as did the Islamic architects of the Alhambra in Spain; both used many different tessellating shapes. The Dutch graphic artist, M.C. Escher (1898-1972) famously created pictures with tessellating birds, dogs, lizards and all manner of other things.

When my lecturer used the word "tessellation" it immediately occurred to me that I'd already come across "tessellated" in school geography in connection with a feature in sedimentary rock known as a tessellated pavement, whereby erosion produces the effect of a layer of interlocking tiles. The word "tessera" also popped into my mind. This is the name for the individual pieces of a mosaic such as the Romans used for villa floors or the Byzantines used in their wall mosaics of religious and other subjects. It hadn't occurred to me before, but tessera means tile, more specifically, a 4-sided shape, and its meaning had been extended to describe all close-fit tiling of whatever shape.

On our most recent visit to London we came across a relatively new building near the Thames Cable Car. Ravensbourne College is the work of the Foreign Office Architects and, unusually in a modern British building, it has exterior walls that are tessellated with pentagons and triangles. Interestingly that's not necessarily what the first-time viewer notices because its other distinguishing feature is that every window above the ground floor level is circular! The building is certainly eye-catching. It is located next to the enormous and distinctive O2 (formerly known as the Millennium Dome) so one can understand the architects wanting it to claim its space.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 37.1mm (100mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/200 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Thursday, January 09, 2014

Heraldry and pelicans

click photo to enlarge

When coats of arms and heraldic devices were first conceived animals were widely used symbols. Those chosen were often selected for either their relevance to the family or for their fearsome qualities. Thus, the lion and the eagle are probably the most commonly found mammal and bird. But, as heraldry progressed, a wider range of creatures was used, such as boars, elephants, beavers or stags, and a veritable aviary of birds was put to work representing individuals, organisations and towns on their coats of arms. From the humble martlet (house martin) to the towering ostrich, birds of every description were pressed into service, including the pelican.

Before they featured in heraldry pelicans were used to symbolise Christ's sacrifice on the cross. It was believed that as young pelicans grow they strike their parent on the face with their beaks and the adult bird then kills them. But, after three days mourning the mother pierces her own breast and feeds her blood to the nestlings, which revives them. In an alternate version of this story the young pelicans are poisoned and the adult feeds her blood to bring them back to life. This tale was known from the medieval bestiaries and became part of Christian iconography. It can often be seen in medieval churches as the subject of carving in stone or wood, frequently on the underside of misericords or in ceiling bosses. It is also a popular subject for stained glass as in this Pre-Raphaelite example by Edward Burne-Jones for Morris & Co. that I photographed in the church of St Martin at Brampton, Cumbria.

Before they featured in heraldry pelicans were used to symbolise Christ's sacrifice on the cross. It was believed that as young pelicans grow they strike their parent on the face with their beaks and the adult bird then kills them. But, after three days mourning the mother pierces her own breast and feeds her blood to the nestlings, which revives them. In an alternate version of this story the young pelicans are poisoned and the adult feeds her blood to bring them back to life. This tale was known from the medieval bestiaries and became part of Christian iconography. It can often be seen in medieval churches as the subject of carving in stone or wood, frequently on the underside of misericords or in ceiling bosses. It is also a popular subject for stained glass as in this Pre-Raphaelite example by Edward Burne-Jones for Morris & Co. that I photographed in the church of St Martin at Brampton, Cumbria.

The coat of arms of the Norfolk town of King's Lynn has been modified down the centuries but has usually included a pelican (though sometimes a gull). A marine bird is very appropriate for a port, and the designer of the late fifteenth century door shown in today's photograph decided it would be suitable as a central embellishment in the ogee arch that he put above the small wicket door in the centre of the larger main door. It's interesting that this door has survived in a secular property since the late 1400s, though it is noticeable that the surrounding woodwork is repaired and the topmost arch is characteristic of the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: crop of 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f1.8

Shutter Speed: 1/30 sec

ISO:320

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

When coats of arms and heraldic devices were first conceived animals were widely used symbols. Those chosen were often selected for either their relevance to the family or for their fearsome qualities. Thus, the lion and the eagle are probably the most commonly found mammal and bird. But, as heraldry progressed, a wider range of creatures was used, such as boars, elephants, beavers or stags, and a veritable aviary of birds was put to work representing individuals, organisations and towns on their coats of arms. From the humble martlet (house martin) to the towering ostrich, birds of every description were pressed into service, including the pelican.

Before they featured in heraldry pelicans were used to symbolise Christ's sacrifice on the cross. It was believed that as young pelicans grow they strike their parent on the face with their beaks and the adult bird then kills them. But, after three days mourning the mother pierces her own breast and feeds her blood to the nestlings, which revives them. In an alternate version of this story the young pelicans are poisoned and the adult feeds her blood to bring them back to life. This tale was known from the medieval bestiaries and became part of Christian iconography. It can often be seen in medieval churches as the subject of carving in stone or wood, frequently on the underside of misericords or in ceiling bosses. It is also a popular subject for stained glass as in this Pre-Raphaelite example by Edward Burne-Jones for Morris & Co. that I photographed in the church of St Martin at Brampton, Cumbria.

Before they featured in heraldry pelicans were used to symbolise Christ's sacrifice on the cross. It was believed that as young pelicans grow they strike their parent on the face with their beaks and the adult bird then kills them. But, after three days mourning the mother pierces her own breast and feeds her blood to the nestlings, which revives them. In an alternate version of this story the young pelicans are poisoned and the adult feeds her blood to bring them back to life. This tale was known from the medieval bestiaries and became part of Christian iconography. It can often be seen in medieval churches as the subject of carving in stone or wood, frequently on the underside of misericords or in ceiling bosses. It is also a popular subject for stained glass as in this Pre-Raphaelite example by Edward Burne-Jones for Morris & Co. that I photographed in the church of St Martin at Brampton, Cumbria.The coat of arms of the Norfolk town of King's Lynn has been modified down the centuries but has usually included a pelican (though sometimes a gull). A marine bird is very appropriate for a port, and the designer of the late fifteenth century door shown in today's photograph decided it would be suitable as a central embellishment in the ogee arch that he put above the small wicket door in the centre of the larger main door. It's interesting that this door has survived in a secular property since the late 1400s, though it is noticeable that the surrounding woodwork is repaired and the topmost arch is characteristic of the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: crop of 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f1.8

Shutter Speed: 1/30 sec

ISO:320

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Tuesday, January 07, 2014

Churchyard gravestones

click photo to enlarge

Standing in Quadring churchyard the other morning, my fingers chilly on the cold metal of the camera, I started to move about in an attempt to keep the recent, black marble gravestones out of the composition of my photograph. There is no doubt that, among the lichen encrusted oolitic limestone and the green and grey of the slate from Swithland and elsewhere that is characteristic of the older gravestones, these newer examples stick out like the proverbial sore thumbs. Over the years, and in different localities, church authorities have periodically tried to bring some aesthetic harmony to gravestones, particularly where they are being sited next to outstanding old examples, or where the churchyard is particularly uniform in this regard, or is especially picturesque. I have some sympathy for these attempts, and yet I can see a sound argument against it too.

At the very minimum, in sensitive churchyards, I'd like to see local stone, or stone that was been used down the centuries, or a stone that is similar to the traditional type, continue in use in the interests of visual harmony. In a churchyard such as that at Quadring areas of similarly styled gravestones tend to be grouped together according to the few decades in which they were erected, with the oldest the closest to the south, west and east of the church. Imported marble appears in the Victorian period and thereafter increases in both quantity and stridency. The currently fashionable glossy black examples with incised gold lettering jars with everything around them. Perhaps they'll weather to an acceptable finish, but I doubt it. Of course, were my prescription to be followed then the fertility of the memorial designer's art would be somewhat curtailed and the possibility of a new and admirable wave of gravestones appearing is lessened. That is the main disadvantage. On balance, however, I'd take that over the agglomeration of styles that sit awkwardly together today, with quite the worse being those made in the decades either side of about 1920, badly finished stone with letters and numbers fixed to their surface, looking drab and nondescript barely a hundred years after making.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/320 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Standing in Quadring churchyard the other morning, my fingers chilly on the cold metal of the camera, I started to move about in an attempt to keep the recent, black marble gravestones out of the composition of my photograph. There is no doubt that, among the lichen encrusted oolitic limestone and the green and grey of the slate from Swithland and elsewhere that is characteristic of the older gravestones, these newer examples stick out like the proverbial sore thumbs. Over the years, and in different localities, church authorities have periodically tried to bring some aesthetic harmony to gravestones, particularly where they are being sited next to outstanding old examples, or where the churchyard is particularly uniform in this regard, or is especially picturesque. I have some sympathy for these attempts, and yet I can see a sound argument against it too.

At the very minimum, in sensitive churchyards, I'd like to see local stone, or stone that was been used down the centuries, or a stone that is similar to the traditional type, continue in use in the interests of visual harmony. In a churchyard such as that at Quadring areas of similarly styled gravestones tend to be grouped together according to the few decades in which they were erected, with the oldest the closest to the south, west and east of the church. Imported marble appears in the Victorian period and thereafter increases in both quantity and stridency. The currently fashionable glossy black examples with incised gold lettering jars with everything around them. Perhaps they'll weather to an acceptable finish, but I doubt it. Of course, were my prescription to be followed then the fertility of the memorial designer's art would be somewhat curtailed and the possibility of a new and admirable wave of gravestones appearing is lessened. That is the main disadvantage. On balance, however, I'd take that over the agglomeration of styles that sit awkwardly together today, with quite the worse being those made in the decades either side of about 1920, badly finished stone with letters and numbers fixed to their surface, looking drab and nondescript barely a hundred years after making.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/320 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Sunday, January 05, 2014

Just a couple of sunsets

click photo to enlarge

Just?! There's nothing just about a sunset! It surely counts among the most wonderful sights that the planet earth can offer. Imagine how much poorer we would be if the sky no longer turned to fire, if clouds ceased to be tinged by red, orange, pink and purple. Consider losing the transformative effect that a sunset can bring to the grimmest urban scene, the most unremarkable suburban streetscape or an over-regimented, industrialised, agricultural landscape. Think for a moment about how rivers, lakes, west facing coastlines, even humble puddles, would no longer be able to double the power of the fiery sky with their reflections. Or how we would no longer feel that familiar thrill as we stopped and stared at the sky, watching as the colours start to build to a blazing climax then subside to a glimmer, a mere memory of what has come and gone.

I've said elsewhere that seeing a sunset, any sunset, is like seeing one for the first time. It dazzles the eye and lifts the spirits. I felt that way the other afternoon as we had a late walk round the village and the clouds turned first pink and yellow, then a deeper orange and red. It came upon us as we were on some of the plainer streets, away from the church, the stream and the big trees of the village's picturesque centre. But that didn't matter; the transformation took place regardless. After taking my fill of the spectacular sunset I took a couple of shots to remember it by.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: crop of 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5

Shutter Speed: 1/30 sec

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Just?! There's nothing just about a sunset! It surely counts among the most wonderful sights that the planet earth can offer. Imagine how much poorer we would be if the sky no longer turned to fire, if clouds ceased to be tinged by red, orange, pink and purple. Consider losing the transformative effect that a sunset can bring to the grimmest urban scene, the most unremarkable suburban streetscape or an over-regimented, industrialised, agricultural landscape. Think for a moment about how rivers, lakes, west facing coastlines, even humble puddles, would no longer be able to double the power of the fiery sky with their reflections. Or how we would no longer feel that familiar thrill as we stopped and stared at the sky, watching as the colours start to build to a blazing climax then subside to a glimmer, a mere memory of what has come and gone.

I've said elsewhere that seeing a sunset, any sunset, is like seeing one for the first time. It dazzles the eye and lifts the spirits. I felt that way the other afternoon as we had a late walk round the village and the clouds turned first pink and yellow, then a deeper orange and red. It came upon us as we were on some of the plainer streets, away from the church, the stream and the big trees of the village's picturesque centre. But that didn't matter; the transformation took place regardless. After taking my fill of the spectacular sunset I took a couple of shots to remember it by.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: crop of 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5

Shutter Speed: 1/30 sec

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, January 03, 2014

Devil's Alley and other street names

click photo to enlarge

Today's photograph shows an alley in King's Lynn, Norfolk. It stretches back from Nelson Street towards the quayside. Entry is through a carriage arch that gives access to the rear of the old houses that line this architecturally fascinating road. The narrow way goes by the name of Devil's Alley. The story goes that the devil arrived in King's Lynn by ship and slipped ashore to gather up some new souls. However, a priest followed him to this particular alley and used the power of prayer and holy water to drive him back to his ship. During his retreat the devil, annoyed at being thwarted, apparently stamped his foot so hard that it left an imprint in the alley. At one time a cobble could be seen that had an imprint like a large human foot, but this is no longer to be found.

The unusual name of this alley got me thinking about some of the other street names that have caught my eye down the years. The most recent is Breakneck Lane in Louth, Lincolnshire, a not especially steep, but quite narrow road, and one that may have caused people to come to grief in the past, perhaps the rider of the phantom horse that has allegedly been heard galloping down it! Then there is Whip-ma-whop-ma-gate in York. The derivation of this name is unclear: both "What a street!" and "Neither one thing or the other" have their supporters - the street is very short. When I lived in Kingston upon Hull I was very taken with the street name, Land of Green Ginger. This name has prompted many suggestions for its origin: from a place where spices were traded in the medieval period to "Lindegroen jonger"(Lindegreen Junior), a name associated with a Dutch family who lived there in the early nineteenth century.Other memorable examples include Dog and Duck Lane, Beverley (named after a pub), Bodkin Lane on Lancashire's Fylde (watch out for dagger-armed robbers) and Lowe's Wong, Southwell, in Nottinghamshire. If you thought wong has an oriental connection you'd be wrong; like "wang" it is from the Danish for garden or in-field and dates from the time of the Norse invasions of the ninth and tenth centuries AD.

You may be wondering if today's photograph was fortuitously lit. It wasn't, I added a vignette to give it an appropriately dark aspect.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 17.6mm (47mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f3.2 Shutter Speed: 1/50 sec

ISO:160

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Today's photograph shows an alley in King's Lynn, Norfolk. It stretches back from Nelson Street towards the quayside. Entry is through a carriage arch that gives access to the rear of the old houses that line this architecturally fascinating road. The narrow way goes by the name of Devil's Alley. The story goes that the devil arrived in King's Lynn by ship and slipped ashore to gather up some new souls. However, a priest followed him to this particular alley and used the power of prayer and holy water to drive him back to his ship. During his retreat the devil, annoyed at being thwarted, apparently stamped his foot so hard that it left an imprint in the alley. At one time a cobble could be seen that had an imprint like a large human foot, but this is no longer to be found.

The unusual name of this alley got me thinking about some of the other street names that have caught my eye down the years. The most recent is Breakneck Lane in Louth, Lincolnshire, a not especially steep, but quite narrow road, and one that may have caused people to come to grief in the past, perhaps the rider of the phantom horse that has allegedly been heard galloping down it! Then there is Whip-ma-whop-ma-gate in York. The derivation of this name is unclear: both "What a street!" and "Neither one thing or the other" have their supporters - the street is very short. When I lived in Kingston upon Hull I was very taken with the street name, Land of Green Ginger. This name has prompted many suggestions for its origin: from a place where spices were traded in the medieval period to "Lindegroen jonger"(Lindegreen Junior), a name associated with a Dutch family who lived there in the early nineteenth century.Other memorable examples include Dog and Duck Lane, Beverley (named after a pub), Bodkin Lane on Lancashire's Fylde (watch out for dagger-armed robbers) and Lowe's Wong, Southwell, in Nottinghamshire. If you thought wong has an oriental connection you'd be wrong; like "wang" it is from the Danish for garden or in-field and dates from the time of the Norse invasions of the ninth and tenth centuries AD.

You may be wondering if today's photograph was fortuitously lit. It wasn't, I added a vignette to give it an appropriately dark aspect.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 17.6mm (47mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f3.2 Shutter Speed: 1/50 sec

ISO:160

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, January 01, 2014

Notoriety, fame, Newton and Thatcher

click photo to enlarge

"Fame, we may understand, is no sure test of merit, but only a probability of such: it is an accident, not a property of a man." Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) Scottish philosopher, essayist and historian

My first introduction to the architecturally preposterous tower of Grantham town hall was in the 1970s, from the train, as we passed through on our way to London. We were living in the city of Kingston upon Hull at the time and the east coast mainline goes through the town. Not until thirty or so years later did I visit Grantham, have a walk around, and take in the full splendour of William Watkins' hodgepodge building. By that time the town had gained some notoriety as the place where Margaret Thatcher was born. Admirers of our first woman prime minister see her birthplace, her father's grocery shop, as something of a shrine. I have no such illusions, regarding her as a stain on our country's life and history, a divisive politician who abandoned the post-war consensus and returned Britain to a society of haves and have-nots.

On that first visit I also became aware of Grantham's connection with the great scientist, Isaac Newton. The town isn't his birthplace; he was born in nearby Woolsthorpe Manor. However, it was the place where, between 1655 and 1661, he was educated. The Free Grammar School dates back to 1327 though the oldest currently standing buildings, ones that Newton would have sat in, were erected in about 1497. Education still takes place there today, but it is now known as The King's School. Grantham is sufficiently proud of the connection with Newton to have erected his statue in the main civic space in front of the town hall. There can be no denying Newton's achievements and it is right that he is recognised in this way. As I took my photograph the other day I wondered whether, in the fullness of time, Margaret Thatcher would take her place alongside him. In Britain we are, quite rightly, wary of commissioning statues to the living. There seems to be a recognition that time can change the esteem with which the famous are regarded. The death of Margaret Thatcher last year has prompted calls for public statues as a tribute to her achievements. I feel that generally, and especially in the north of England, Scotland and Wales, the public mood would not welcome such a step. However, the one place where that feeling might not prevail is the place of her birth. I will, with interest, watch the space next to Newton in front of Grantham's hideous town hall.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 19.1mm (51mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5

Shutter Speed: 1/60 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

"Fame, we may understand, is no sure test of merit, but only a probability of such: it is an accident, not a property of a man." Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) Scottish philosopher, essayist and historian

My first introduction to the architecturally preposterous tower of Grantham town hall was in the 1970s, from the train, as we passed through on our way to London. We were living in the city of Kingston upon Hull at the time and the east coast mainline goes through the town. Not until thirty or so years later did I visit Grantham, have a walk around, and take in the full splendour of William Watkins' hodgepodge building. By that time the town had gained some notoriety as the place where Margaret Thatcher was born. Admirers of our first woman prime minister see her birthplace, her father's grocery shop, as something of a shrine. I have no such illusions, regarding her as a stain on our country's life and history, a divisive politician who abandoned the post-war consensus and returned Britain to a society of haves and have-nots.

On that first visit I also became aware of Grantham's connection with the great scientist, Isaac Newton. The town isn't his birthplace; he was born in nearby Woolsthorpe Manor. However, it was the place where, between 1655 and 1661, he was educated. The Free Grammar School dates back to 1327 though the oldest currently standing buildings, ones that Newton would have sat in, were erected in about 1497. Education still takes place there today, but it is now known as The King's School. Grantham is sufficiently proud of the connection with Newton to have erected his statue in the main civic space in front of the town hall. There can be no denying Newton's achievements and it is right that he is recognised in this way. As I took my photograph the other day I wondered whether, in the fullness of time, Margaret Thatcher would take her place alongside him. In Britain we are, quite rightly, wary of commissioning statues to the living. There seems to be a recognition that time can change the esteem with which the famous are regarded. The death of Margaret Thatcher last year has prompted calls for public statues as a tribute to her achievements. I feel that generally, and especially in the north of England, Scotland and Wales, the public mood would not welcome such a step. However, the one place where that feeling might not prevail is the place of her birth. I will, with interest, watch the space next to Newton in front of Grantham's hideous town hall.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 19.1mm (51mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5

Shutter Speed: 1/60 sec

ISO:125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On