click photo to enlarge

A camera never reproduces exactly what your eye sees but in some circumstances the results are way off. Shooting into the light often has unexpected outcomes. Sometimes the shot has high contrast and is very dramatic. At other times the light meter makes a wrong guess and either exposes the sky correctly but leaves the land unnaturally dark, or it exposes the land properly but the nicely figured sky and clouds are blown out to pure white. Cameras can't yet show the range of gradations between black and white that the eye can see though techniques such as multiple exposures and shadow boosting are making inroads into the deficit. Photographers are, by and large, able to work with this inaccuracy and sometimes welcome the camera's results because they "improve" on what the eye saw. At other times extensive digital manipulation is required to bring a better balance and greater verisimilitude to, say, a landscape where the photographer was forced to shoot against the light.

I found myself in that situation a couple of weeks ago. We were passing through Cley next the Sea in Norfolk, the location of one of the most photographed windmills in England, and I thought I'd try for a shot of it in its setting. However, it was half an hour past noon in mid-August, not the best time for landscape photography. Moreover, the view I wanted required me to shoot into the light. The result was a series of images with good sky but dark buildings, marsh and woodland. That's not what my eye saw; the scene was quite brightly lit. So, when I got home I sat down for half and hour or so with the image on the computer and tried to convert my badly exposed shot into something closer to what I saw.

Was I successful? How do you judge success? It's very hard to remember exactly how the scene looked and the relative brightness of all the elements. I suppose one measure of success is that the shot looks natural to someone who wasn't there with me. And yet, I fear that we are sufficiently far down the road in digital photography and manipulation that many people and even more photographers no longer have a secure grasp of what looks "real" in photographs. I find myself questioning some of the shots that my newspaper presents as a record of an event, and some of the images I see on forums, in photography magazines and in competitions appear to have been taken on a planet other than earth, such is the level of saturation and the balance of tones. Another measure of success is that it looks right to me. This one isn't quite right. Nor is the smaller photograph of the beach huts at Sheringham. But they are both closer to what I saw than the images the camera recorded.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 67mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/800 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Pages

▼

Saturday, August 31, 2013

Thursday, August 29, 2013

Price, value and Oscar Wilde

click photo to enlarge

"Nowadays people know the price of everything and the value of nothing." (from "The Picture of Dorian Grey")

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), Irish writer and poet

The quotation above is delivered by Oscar Wilde's character, Lord Henry, in the course of an apology for lateness - "I went to look after a piece of old brocade in Wardour Street and had to bargain for hours for it. Nowadays people know the price of everything and the value of nothing." However, it seems to me that for many years it has accurately summarised the attitude of British politicians, both national and local. Our coalition government is cutting state spending, particularly that by local government with a barely disguised zeal. Under the pretext of "balancing the books" and "clearing up the mess left by the previous government" they are doing what their political philosophy of "shrinking the state" would have led them to do in any circumstances.

The effect of this in the wider country, particularly where the political complexion is the same as that at national level, is that services are being hacked to pieces. Lincolnshire County Council wants to reduce the spending on its library service by one third, closing many libraries, and hoping that volunteers will step in to fill the void created. In Boston the council is seeking to attract businesses to the town and at the same time is selling off public buildings in order to generate income and reduce outgoings. The glass fronted building in today's photograph used to be an art gallery and community space. For the past few years it has been empty, the only thing on display being a sign advertising its suitability for offices. There have been no takers. What the local council don't seem to realise is that companies looking to locate in an area, and attract workers to their businesses, are influenced by the cultural services available. Many new industries will only establish themselves in a place that offers their workforce theatres, galleries, public parks and facilities that give a buzz to the area. Politicians who close galleries and libraries whilst at the same time working to increase jobs in their area epitomise Wilde's quotation to perfection. It also brings to mind E. M. Forster in "Howard's End" - "Only connect!"

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/200

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

"Nowadays people know the price of everything and the value of nothing." (from "The Picture of Dorian Grey")

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), Irish writer and poet

The quotation above is delivered by Oscar Wilde's character, Lord Henry, in the course of an apology for lateness - "I went to look after a piece of old brocade in Wardour Street and had to bargain for hours for it. Nowadays people know the price of everything and the value of nothing." However, it seems to me that for many years it has accurately summarised the attitude of British politicians, both national and local. Our coalition government is cutting state spending, particularly that by local government with a barely disguised zeal. Under the pretext of "balancing the books" and "clearing up the mess left by the previous government" they are doing what their political philosophy of "shrinking the state" would have led them to do in any circumstances.

The effect of this in the wider country, particularly where the political complexion is the same as that at national level, is that services are being hacked to pieces. Lincolnshire County Council wants to reduce the spending on its library service by one third, closing many libraries, and hoping that volunteers will step in to fill the void created. In Boston the council is seeking to attract businesses to the town and at the same time is selling off public buildings in order to generate income and reduce outgoings. The glass fronted building in today's photograph used to be an art gallery and community space. For the past few years it has been empty, the only thing on display being a sign advertising its suitability for offices. There have been no takers. What the local council don't seem to realise is that companies looking to locate in an area, and attract workers to their businesses, are influenced by the cultural services available. Many new industries will only establish themselves in a place that offers their workforce theatres, galleries, public parks and facilities that give a buzz to the area. Politicians who close galleries and libraries whilst at the same time working to increase jobs in their area epitomise Wilde's quotation to perfection. It also brings to mind E. M. Forster in "Howard's End" - "Only connect!"

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/200

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Tuesday, August 27, 2013

Windows, frames and light

click photo to enlarge

Commercial buildings of today have virtually banished the window as a discrete architectural feature. Glass curtain walls have made the window as a transparent opening in a solid, opaque wall seem like a quaint artefact of the past and have merged the features of the elevation into nothing less than a giant mirror. However, in traditionally built houses the window continues, a hole that admits necessary light and that also frames the inhabitants' views of their surroundings.

Down the centuries windows have changed and evolved. Early medieval examples were often simply apertures, left open when the weather was kind and calm, covered with translucent greased cloth when inclement and windy. I've seen sixteenth century windows filled with glazed, iron casement windows that were only an approximation of the shape they filled, through which draughts must have whistled and where heavy curtains were required for any kind of winter warmth. Today's house windows tend towards the utilitarian, their plastic frames requiring neither paint nor a second glance.

Some of the most elegant windows date from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries when simplicity and proportion were imposed on window design in a way that we could learn from today. I came across an example recently in the Guildhall in Boston, Lincolnshire. This mid fifteenth century building, erected for the Guild of the Blessed Virgin Mary, has been added to and modified over the years. Some of the upstairs windows were replaced in the eighteenth century and it was one of these that I stopped by to look down into the garden of Fydell House (also eighteenth century) next door. The way the light and sharp shadows fell across the fielded panels of the internal shutters had caught my eye, and as I looked at the nine-over-nine sash window and the view through the panes I was moved to take this photograph. What had appealed to me was one of the fundamental attractions of traditional windows that have all but disappeared where curtain walls have taken over, namely the way the entry of light models the interior and the way the firm outline of the window frames the world outside. It's a charming attribute that a painter such as Vermeer could build a career on and it's something that has the capacity to captivate us still.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/500

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Commercial buildings of today have virtually banished the window as a discrete architectural feature. Glass curtain walls have made the window as a transparent opening in a solid, opaque wall seem like a quaint artefact of the past and have merged the features of the elevation into nothing less than a giant mirror. However, in traditionally built houses the window continues, a hole that admits necessary light and that also frames the inhabitants' views of their surroundings.

Down the centuries windows have changed and evolved. Early medieval examples were often simply apertures, left open when the weather was kind and calm, covered with translucent greased cloth when inclement and windy. I've seen sixteenth century windows filled with glazed, iron casement windows that were only an approximation of the shape they filled, through which draughts must have whistled and where heavy curtains were required for any kind of winter warmth. Today's house windows tend towards the utilitarian, their plastic frames requiring neither paint nor a second glance.

Some of the most elegant windows date from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries when simplicity and proportion were imposed on window design in a way that we could learn from today. I came across an example recently in the Guildhall in Boston, Lincolnshire. This mid fifteenth century building, erected for the Guild of the Blessed Virgin Mary, has been added to and modified over the years. Some of the upstairs windows were replaced in the eighteenth century and it was one of these that I stopped by to look down into the garden of Fydell House (also eighteenth century) next door. The way the light and sharp shadows fell across the fielded panels of the internal shutters had caught my eye, and as I looked at the nine-over-nine sash window and the view through the panes I was moved to take this photograph. What had appealed to me was one of the fundamental attractions of traditional windows that have all but disappeared where curtain walls have taken over, namely the way the entry of light models the interior and the way the firm outline of the window frames the world outside. It's a charming attribute that a painter such as Vermeer could build a career on and it's something that has the capacity to captivate us still.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/500

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Sunday, August 25, 2013

Semi-abstract, man and nature

click photo to enlarge

When it comes to composing photographs of a semi-abstract nature I've always found it easier to use man-made subjects. By judicious selection I've often put together images that ignore the reality of what is on view and encourage the viewer to see simply colour, shape, line, tone etc. Living in close proximity to fairly large urban areas near the Fylde coast of Lancashire it was easier to find such subjects. Moving to rural Lincolnshire I've found it much harder and have had to re-think my approach. But, over the past few years, I've started to see possibilities in reeds, trees, water, ice, flowers etc.

On our recent shopping trip to King's Lynn I leaned over the quayside of the River Great Ouse, the RX100 gripped tightly in hand, and looked down at the incoming tide. The slowly rising river was gradually covering two banks of mud that had been exposed at low tide. On the surface of the water I could see the reflections of the clouds and blue sky, with shafts of sunlight making momentary appearances. The two areas of mud looked like a pair of amorous whales casting their eyes over one another, and so with the actuality of what I was seeing banished from my mind by the reflections and my imagination I took my shot. It isn't the best "natural semi-abstract" photograph I've ever taken. In fact I'd be hard pressed to describe why I quite like it and what qualities it has that make me think it suitable for posting. But then sometimes one doesn't have to explain why something appeals; a visceral feeling is quite sufficient.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/60

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

When it comes to composing photographs of a semi-abstract nature I've always found it easier to use man-made subjects. By judicious selection I've often put together images that ignore the reality of what is on view and encourage the viewer to see simply colour, shape, line, tone etc. Living in close proximity to fairly large urban areas near the Fylde coast of Lancashire it was easier to find such subjects. Moving to rural Lincolnshire I've found it much harder and have had to re-think my approach. But, over the past few years, I've started to see possibilities in reeds, trees, water, ice, flowers etc.

On our recent shopping trip to King's Lynn I leaned over the quayside of the River Great Ouse, the RX100 gripped tightly in hand, and looked down at the incoming tide. The slowly rising river was gradually covering two banks of mud that had been exposed at low tide. On the surface of the water I could see the reflections of the clouds and blue sky, with shafts of sunlight making momentary appearances. The two areas of mud looked like a pair of amorous whales casting their eyes over one another, and so with the actuality of what I was seeing banished from my mind by the reflections and my imagination I took my shot. It isn't the best "natural semi-abstract" photograph I've ever taken. In fact I'd be hard pressed to describe why I quite like it and what qualities it has that make me think it suitable for posting. But then sometimes one doesn't have to explain why something appeals; a visceral feeling is quite sufficient.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/60

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, August 23, 2013

Semi-abstract, addition and subtraction

click photo to enlarge

I've mentioned semi-abstract photography, why I use the term, what it is and why I like it, it in posts of 2007 (Blackpool semi-abstract), 2009 (Why semi-abstract photography) and 2010 (A light, stairs and abstraction). Over the years I've also included in the blog many photographs of this genre, some of which I count among my favourite shots.

On a recent shopping expedition to King's Lynn in Norfolk I got another example for my collection. It is, I suppose, one of those photographs that is an acquired taste; the sort of image that appears only in the ouvre of enthusiast photographers. And yet, as I prepared the shot for publication, I reflected that the means of arriving at this particular subject and composition is precisely the same as for any other kind of photograph.

In a way it is easier to appreciate the process of putting together a photograph if we compare it with a similar but different process, so let's for a moment think about the artist with their brushes. The artist starts with a blank canvas and carefully begins to add those elements - real or imagined - that he or she requires in order to arrive at the finished composition: it is essentially an additive process. Photography is approached in a different way and can be thought of as the opposite of this method of working. What photographers do is survey the scene before them, a scene that is potentially 360° in circumference as well as extending above and below, and settles on a small part of it to include in the camera viewfinder. The photographer moves the camera (or zooms the lens) to exclude from the viewfinder anything that isn't needed in the final composition: it is a subtractive process.

As I stood idly in a fairly recently built shopping precinct, waiting for my wife, I did just that. I gazed at the rectangular elements of the upper part of the walls and selected a segment for my photograph that I thought would make a visually interesting composition. I included a rather odd-looking light and some sky. I tried to make the arrangement have balance, contrast, cohesion and harmony. I was looking for a calm, restful and precise photograph where the subject is less important than the colours, shapes, lines etc. I'm not displeased with the outcome.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 37.1mm (100mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/640

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

I've mentioned semi-abstract photography, why I use the term, what it is and why I like it, it in posts of 2007 (Blackpool semi-abstract), 2009 (Why semi-abstract photography) and 2010 (A light, stairs and abstraction). Over the years I've also included in the blog many photographs of this genre, some of which I count among my favourite shots.

On a recent shopping expedition to King's Lynn in Norfolk I got another example for my collection. It is, I suppose, one of those photographs that is an acquired taste; the sort of image that appears only in the ouvre of enthusiast photographers. And yet, as I prepared the shot for publication, I reflected that the means of arriving at this particular subject and composition is precisely the same as for any other kind of photograph.

In a way it is easier to appreciate the process of putting together a photograph if we compare it with a similar but different process, so let's for a moment think about the artist with their brushes. The artist starts with a blank canvas and carefully begins to add those elements - real or imagined - that he or she requires in order to arrive at the finished composition: it is essentially an additive process. Photography is approached in a different way and can be thought of as the opposite of this method of working. What photographers do is survey the scene before them, a scene that is potentially 360° in circumference as well as extending above and below, and settles on a small part of it to include in the camera viewfinder. The photographer moves the camera (or zooms the lens) to exclude from the viewfinder anything that isn't needed in the final composition: it is a subtractive process.

As I stood idly in a fairly recently built shopping precinct, waiting for my wife, I did just that. I gazed at the rectangular elements of the upper part of the walls and selected a segment for my photograph that I thought would make a visually interesting composition. I included a rather odd-looking light and some sky. I tried to make the arrangement have balance, contrast, cohesion and harmony. I was looking for a calm, restful and precise photograph where the subject is less important than the colours, shapes, lines etc. I'm not displeased with the outcome.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 37.1mm (100mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/640

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

Hunstanton's striped cliffs

click photo to enlarge

The sea cliffs of Hunstanton are one of the most visually striking geological formations in England. The strata comprises essentially three layers of rock. At the top is the Upper Cretaceous white/grey chalk known as the the Ferriby Chalk Formation. Below that is the brick coloured Hunstanton Red Chalk Formation formed during the Lower Cretaceous period. The red colour of this stone is due to ferrous staining. The dark brown, lower layer is Carstone (also spelled carrstone). Like the chalk above it this Lower Cretacaous red sandstone acquired its hue through the presence of iron.

The latter stone is widely used in the old buildings of Hunstanton. In wider Norfolk it is found in buildings in a zone that runs north-south down the eastern bank of the Wash from Thornham to around Stoke Ferry, but is especially seen in the area between Hunstanton and Castle Rising. In this region it was used alone in courses, with flint in chequerwork, and as infill with brick surrounds and quoins. Its use declined markedly after the first world war, but it is being used again in new buildings that echo traditional styles, often as a decorative finish over breeze-blocks in a flat area of wall that is enclosed by brick work. The smaller photograph shows Hunstanton Town Hall, a building of 1896, where the carstone is used around the arch in chequerwork with ashlar but also as a random, almost rubble facing in between the cut stone pilasters and the carstone blocks of the window surrounds. The term "gingerbread work" has been used to describe this way of using the distinctive, cake-coloured stone.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 105mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/200 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

The sea cliffs of Hunstanton are one of the most visually striking geological formations in England. The strata comprises essentially three layers of rock. At the top is the Upper Cretaceous white/grey chalk known as the the Ferriby Chalk Formation. Below that is the brick coloured Hunstanton Red Chalk Formation formed during the Lower Cretaceous period. The red colour of this stone is due to ferrous staining. The dark brown, lower layer is Carstone (also spelled carrstone). Like the chalk above it this Lower Cretacaous red sandstone acquired its hue through the presence of iron.

The latter stone is widely used in the old buildings of Hunstanton. In wider Norfolk it is found in buildings in a zone that runs north-south down the eastern bank of the Wash from Thornham to around Stoke Ferry, but is especially seen in the area between Hunstanton and Castle Rising. In this region it was used alone in courses, with flint in chequerwork, and as infill with brick surrounds and quoins. Its use declined markedly after the first world war, but it is being used again in new buildings that echo traditional styles, often as a decorative finish over breeze-blocks in a flat area of wall that is enclosed by brick work. The smaller photograph shows Hunstanton Town Hall, a building of 1896, where the carstone is used around the arch in chequerwork with ashlar but also as a random, almost rubble facing in between the cut stone pilasters and the carstone blocks of the window surrounds. The term "gingerbread work" has been used to describe this way of using the distinctive, cake-coloured stone.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 105mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/200 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Monday, August 19, 2013

Views from Cromer pier

click photo to enlarge

Victorian and Edwardian recreational piers make great photographic subjects. They stretch out from the shore into the sea, a wooden deck with pavilions, theatres, shops, shelters and railings, supported by a forest of cast iron or steel legs and cross bracing. Ornate metalwork, fanciful roof outlines, flagpoles and other excrescences make for lively shapes against sea and sky. People flock to them seeking the experience of being at sea without setting foot in a precarious boat or sickness inducing ship. Fishermen seek them out for the opportunity they offer to easily cast into deep water. Yes, piers offer the photographer subjects a-plenty.

However, piers offer more than a subject. The photographer at the coast, casting around for a vantage point from which to take shots of land, the sea or the beach, can do a lot worse than position himself on a pier. I've been fortunate to have lived in the vicinity of piers for a large part of my life and I've frequently taken the opportunity of standing on one in search of a striking or unusual composition. The other day I was in Cromer, Norfolk, doing just that and I came away with a couple of views of the shore that please me. Both were taken fairly early on a Sunday morning before most holidaymakers were stirring. Both feature Cromer's medieval church with its tall tower, described by Pevsner as, "at 160 feet, by far the tallest of any Norfolk parish church." And both show the zig-zag sloping path that takes the pedestrian down to the pier entrance from the viewpoint in front of the Hotel de Paris (1895-6). But, only the smaller photograph shows the pier itself, a structure of 1900-1. It is currently undergoing a refurbishment and has "clutter" on its decking so I kept the amount in the frame to just enough for a strong leading line to the church and hotel. The main photograph, though the colour is not as interesting as in the smaller shot, has a composition that I like better, with the groynes, sea-wall, church tower and line of buildings combining asymmetrically to good effect.

If you want to see what the pier looks like in totality these views taken a couple of years ago tell the tale.

photographs and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 40mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/500 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Victorian and Edwardian recreational piers make great photographic subjects. They stretch out from the shore into the sea, a wooden deck with pavilions, theatres, shops, shelters and railings, supported by a forest of cast iron or steel legs and cross bracing. Ornate metalwork, fanciful roof outlines, flagpoles and other excrescences make for lively shapes against sea and sky. People flock to them seeking the experience of being at sea without setting foot in a precarious boat or sickness inducing ship. Fishermen seek them out for the opportunity they offer to easily cast into deep water. Yes, piers offer the photographer subjects a-plenty.

However, piers offer more than a subject. The photographer at the coast, casting around for a vantage point from which to take shots of land, the sea or the beach, can do a lot worse than position himself on a pier. I've been fortunate to have lived in the vicinity of piers for a large part of my life and I've frequently taken the opportunity of standing on one in search of a striking or unusual composition. The other day I was in Cromer, Norfolk, doing just that and I came away with a couple of views of the shore that please me. Both were taken fairly early on a Sunday morning before most holidaymakers were stirring. Both feature Cromer's medieval church with its tall tower, described by Pevsner as, "at 160 feet, by far the tallest of any Norfolk parish church." And both show the zig-zag sloping path that takes the pedestrian down to the pier entrance from the viewpoint in front of the Hotel de Paris (1895-6). But, only the smaller photograph shows the pier itself, a structure of 1900-1. It is currently undergoing a refurbishment and has "clutter" on its decking so I kept the amount in the frame to just enough for a strong leading line to the church and hotel. The main photograph, though the colour is not as interesting as in the smaller shot, has a composition that I like better, with the groynes, sea-wall, church tower and line of buildings combining asymmetrically to good effect.

If you want to see what the pier looks like in totality these views taken a couple of years ago tell the tale.

photographs and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 40mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/500 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Saturday, August 17, 2013

Obsolescence, repairs and tractors

click photo to enlarge

My web browser bookmarks include a folder marked DIY. It lists sites and web pages that I've found useful when it comes to fixing things or undertaking jobs around the house.With a bit of internet help I've managed to repair the cooker, heating radiators, the car, computers, plumbing, a camera and much more. To be able to do such things gives one a sense of satisfaction, saves money and does something for the environment by extending the life of objects.

However, during my lifetime the number things that are repairable has seemed to become ever fewer. Obsolescence appears to be built into more and more products. Items are made difficult or impossible to open without breaking something, spare parts are unavailable or deliberately expensive, non-standard screws or worse still, glue, are used to fix components together, and records show that often the same component lasts the same limited life-span in a particular product - usually a month or two after the expiry of the warranty! It really looks like some manufacturers construct products to fail after a relatively short time, and make them irreparable by the user or even a technician, in the expectation that it will result in another sale. This marketing ploy is additional to the regular "product-upgrade" cycles whereby the latest and greatest additional features are drip-fed into new models on an annual (or more frequent) basis.

A website I sometimes use for repair advice is iFixit. It ranges fairly widely in its coverage, but is particularly useful for electronics. The staff frequently do what are called "teardowns", i.e. the opening up of new products to see how they are made. Then they pass judgement on their potential for repair. Recently the website published a list of ten electronic devices that are almost impossible to repair. A model of the Apple MacBook Laptop with Retina Display was judged worst in this regard. There were five other Apple product in the list (and two Nikon DSLR cameras). Interestingly their ten easiest to repair electronic devices, published earlier, also included an Apple product.

The sight of this old Fordson Major tractor triggered this line of thought. It's a model from when? The 1960s? I don't know exactly, but it's a good few decades old and still giving service in the harshest of environments: sand and salt water are a recipe for mechanical problems. It is used to haul a crab boat into and out of the sea and its basic, rugged construction, the availability of parts, and the opportunity to improvise or make them where they are unavailable (check out the seat and radiator grille!) means it still works after all these years. I like products that are user-serviceable and user-repairable: they are good for the individual and good for wider society. It would be great if more manufacturers took this into account when they designed their products.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 24mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/320 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

My web browser bookmarks include a folder marked DIY. It lists sites and web pages that I've found useful when it comes to fixing things or undertaking jobs around the house.With a bit of internet help I've managed to repair the cooker, heating radiators, the car, computers, plumbing, a camera and much more. To be able to do such things gives one a sense of satisfaction, saves money and does something for the environment by extending the life of objects.

However, during my lifetime the number things that are repairable has seemed to become ever fewer. Obsolescence appears to be built into more and more products. Items are made difficult or impossible to open without breaking something, spare parts are unavailable or deliberately expensive, non-standard screws or worse still, glue, are used to fix components together, and records show that often the same component lasts the same limited life-span in a particular product - usually a month or two after the expiry of the warranty! It really looks like some manufacturers construct products to fail after a relatively short time, and make them irreparable by the user or even a technician, in the expectation that it will result in another sale. This marketing ploy is additional to the regular "product-upgrade" cycles whereby the latest and greatest additional features are drip-fed into new models on an annual (or more frequent) basis.

A website I sometimes use for repair advice is iFixit. It ranges fairly widely in its coverage, but is particularly useful for electronics. The staff frequently do what are called "teardowns", i.e. the opening up of new products to see how they are made. Then they pass judgement on their potential for repair. Recently the website published a list of ten electronic devices that are almost impossible to repair. A model of the Apple MacBook Laptop with Retina Display was judged worst in this regard. There were five other Apple product in the list (and two Nikon DSLR cameras). Interestingly their ten easiest to repair electronic devices, published earlier, also included an Apple product.

The sight of this old Fordson Major tractor triggered this line of thought. It's a model from when? The 1960s? I don't know exactly, but it's a good few decades old and still giving service in the harshest of environments: sand and salt water are a recipe for mechanical problems. It is used to haul a crab boat into and out of the sea and its basic, rugged construction, the availability of parts, and the opportunity to improvise or make them where they are unavailable (check out the seat and radiator grille!) means it still works after all these years. I like products that are user-serviceable and user-repairable: they are good for the individual and good for wider society. It would be great if more manufacturers took this into account when they designed their products.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 24mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/320 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Thursday, August 15, 2013

Who shot the photographer?

click photo to enlarge

I was reflecting on the word "shoot" the other day. In particular I was wondering how long it had been an English synonym for "take photographs". A quick look at the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) shows the earliest recorded use of "shoot" in the sense of "a discharge of arrows, bullets etc" being 1534 though in Old English an example is quoted from the early poem, The Battle of Maldon (993). As I worked my way down the list of meanings of the word - there are seven main definitions with many subsidiary ones - I tried to guess the date in the 1800s when it might have been transferred to photography. I was well wide of the mark (to use a shooting analogy). The first use that the OED cites is from Anthony's Photographic Bulletin of 1890 and around that date the word "shot" also starts to be used to describe the resulting image itself.

From our twenty first century perspective it might seem unsurprising that the act of taking a photograph should be described thus. After all, as with a gun (or bow) one takes deliberate aim at a target (or subject) and uses ones finger to release a mechanism at a precise moment to achieve the desired outcome. But, when I reconsidered what seemed the relatively late date of 1890, it occurred to me that perhaps the analogy wasn't quite as obvious as we think. After all, the shooting of a gun or arrow often results in a death or injury whereas a shot made with a camera merely fixes a moment in time on paper (or a screen). The former is frequently violent and negative; the latter usually harmless and positive. No, I thought, shooting isn't a word that transfers to photography as naturally as I first thought.

My reflection was prompted by the fact that a few days ago I was being repeatedly shot - by a camera. We were spending some time on the north Norfolk coast at Cromer and the shooter was my wife. Throughout our married life, as our photograph albums testify, I've done most of the family photography and my wife has taken shots mainly to ensure that I appear in the albums periodically. However, on our recent break she made a conscious effort to try and take a few more photographs of me. The result was I kept noticing that as I was taking my photographs I was also being shot. It was relatively painless as I'm a fairly co-operative subject. I've posted two of her shots today. Regular readers may find them a welcome relief from my obscured self-portraits! Incidentally, the rucksack isn't full of photographic equipment. I try to keep the gear and weight to a minimum when I'm out and about. It had only the 70-300mm lens to complement the 24-105mm on the camera. The rest of the weight was essentials for a morning at the coast on a day when a strong breeze was lessening the effects of bright sunshine.

photographs / text © K. Boughen / T. Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 37.1mm (100mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/640

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

I was reflecting on the word "shoot" the other day. In particular I was wondering how long it had been an English synonym for "take photographs". A quick look at the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) shows the earliest recorded use of "shoot" in the sense of "a discharge of arrows, bullets etc" being 1534 though in Old English an example is quoted from the early poem, The Battle of Maldon (993). As I worked my way down the list of meanings of the word - there are seven main definitions with many subsidiary ones - I tried to guess the date in the 1800s when it might have been transferred to photography. I was well wide of the mark (to use a shooting analogy). The first use that the OED cites is from Anthony's Photographic Bulletin of 1890 and around that date the word "shot" also starts to be used to describe the resulting image itself.

From our twenty first century perspective it might seem unsurprising that the act of taking a photograph should be described thus. After all, as with a gun (or bow) one takes deliberate aim at a target (or subject) and uses ones finger to release a mechanism at a precise moment to achieve the desired outcome. But, when I reconsidered what seemed the relatively late date of 1890, it occurred to me that perhaps the analogy wasn't quite as obvious as we think. After all, the shooting of a gun or arrow often results in a death or injury whereas a shot made with a camera merely fixes a moment in time on paper (or a screen). The former is frequently violent and negative; the latter usually harmless and positive. No, I thought, shooting isn't a word that transfers to photography as naturally as I first thought.

My reflection was prompted by the fact that a few days ago I was being repeatedly shot - by a camera. We were spending some time on the north Norfolk coast at Cromer and the shooter was my wife. Throughout our married life, as our photograph albums testify, I've done most of the family photography and my wife has taken shots mainly to ensure that I appear in the albums periodically. However, on our recent break she made a conscious effort to try and take a few more photographs of me. The result was I kept noticing that as I was taking my photographs I was also being shot. It was relatively painless as I'm a fairly co-operative subject. I've posted two of her shots today. Regular readers may find them a welcome relief from my obscured self-portraits! Incidentally, the rucksack isn't full of photographic equipment. I try to keep the gear and weight to a minimum when I'm out and about. It had only the 70-300mm lens to complement the 24-105mm on the camera. The rest of the weight was essentials for a morning at the coast on a day when a strong breeze was lessening the effects of bright sunshine.

photographs / text © K. Boughen / T. Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 37.1mm (100mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/640

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Tuesday, August 13, 2013

Peacocks beautiful, proud and noisy

click photo to enlarge

The Indian Peafowl, the male of which is commonly known as the peacock, is one of the avian world's most brightly coloured members. The electric blue of its body and the iridescent blues and greens of the "eyes" of its tail are very striking. The peacock's shape and the details of its tail have been used in art and design down the centuries, in Europe particularly during the period of Art Nouveau. Moreover, though it is native to India, its popularity is such that it can now be found in virtually every country of the world, often in parks and gardens as well as zoos. In Britain it is frequently found strutting around stately homes or clamouring for attention in collections of birds in wildlife parks. People frequently cite it as their favourite bird or name it the most beautiful of birds.

I can see good qualities in the peacock but it wouldn't feature in even my top 50 favourite birds. I don't think I'm alone in not sharing the general liking of the species, though the naysayers and doubters are very much a minority. If you are someone who wonders why anyone could find fault with this magnificent bird consider this: the word "peacock" can be used as a term of disapprobation, often applied to over-dressed men indulging in what the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) calls "vainglorious display". Such a development surely suggests that some see these qualities in the bird and feel it is useful to purloin the word for that purpose. Whether it's fair to anthropomorphise in this way I leave to you to decide, but clearly not everyone is persuaded by the peacock's magnificent tail and the eye-catching colour.

However, people often acquire likes and dislikes through circumstances peculiar to themselves; that is to say, for reasons that are unlikely to be shared by someone else. So it is with me. Many years ago my wife and I were cycling along a quiet country lane past a farm. Suddenly our ears were unexpectedly assaulted by the piercing cry of a bird only a few feet away that was standing on a wall, at the same height as our heads. It was, of course, a peacock, one we hadn't noticed because of the low hanging branches of the trees. We nearly jumped out of our saddles, such was the explosive force of the unexpected call. Ever since that day I have associated peacocks and their distinctive call with that heart-stopping moment. It is responsible for my enduring negative opinion of the bird.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 300mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/300 sec

ISO: 800

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

The Indian Peafowl, the male of which is commonly known as the peacock, is one of the avian world's most brightly coloured members. The electric blue of its body and the iridescent blues and greens of the "eyes" of its tail are very striking. The peacock's shape and the details of its tail have been used in art and design down the centuries, in Europe particularly during the period of Art Nouveau. Moreover, though it is native to India, its popularity is such that it can now be found in virtually every country of the world, often in parks and gardens as well as zoos. In Britain it is frequently found strutting around stately homes or clamouring for attention in collections of birds in wildlife parks. People frequently cite it as their favourite bird or name it the most beautiful of birds.

I can see good qualities in the peacock but it wouldn't feature in even my top 50 favourite birds. I don't think I'm alone in not sharing the general liking of the species, though the naysayers and doubters are very much a minority. If you are someone who wonders why anyone could find fault with this magnificent bird consider this: the word "peacock" can be used as a term of disapprobation, often applied to over-dressed men indulging in what the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) calls "vainglorious display". Such a development surely suggests that some see these qualities in the bird and feel it is useful to purloin the word for that purpose. Whether it's fair to anthropomorphise in this way I leave to you to decide, but clearly not everyone is persuaded by the peacock's magnificent tail and the eye-catching colour.

However, people often acquire likes and dislikes through circumstances peculiar to themselves; that is to say, for reasons that are unlikely to be shared by someone else. So it is with me. Many years ago my wife and I were cycling along a quiet country lane past a farm. Suddenly our ears were unexpectedly assaulted by the piercing cry of a bird only a few feet away that was standing on a wall, at the same height as our heads. It was, of course, a peacock, one we hadn't noticed because of the low hanging branches of the trees. We nearly jumped out of our saddles, such was the explosive force of the unexpected call. Ever since that day I have associated peacocks and their distinctive call with that heart-stopping moment. It is responsible for my enduring negative opinion of the bird.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 300mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/300 sec

ISO: 800

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Sunday, August 11, 2013

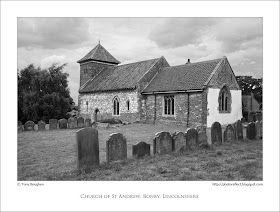

Bonby church - a different view

click photo to enlarge

Today's photograph was taken on the same day as my other black and white shot of Bonby church that I posted recently. It shows the the north side of the building and illustrates something I've discussed elsewhere in this blog, namely how medieval churches were enlarged by adding aisles.

The outline of arcade arches on the nave wall above shows that there was once an aisle attached to the building. It was probably required to accommodate a growing congregation. It may have been added to the original, small aisleless church by knocking out arch-shaped openings in the nave wall and replacing the remaining supporting walling with columns. Of course, when the aisle was added the windows had to be re-positioned (or new ones made) for the new aisle wall that was now farther from the middle of the nave. Sometimes the wall that was turned into an arcade was increased in height and windows were cut through the new, higher section, to shine light into the centre of the church. This solution involved raising the height of the nave roof. I don't know precisely why and how Bonby's aisle was fitted to the original church but it's very clear that at a later date it either became an expensive luxury that a decline in the size of the congregation rendered superfluous; or it fell down; or it became unsafe and was pulled down. Whatever the reason, every expense was spared in restoring the original nave wall. The arches and columns were left in place and simply filled with masonry. I wouldn't be surprised if the aisle windows were re-used too. The architectural effect is inelegant but interesting.

In fact, that description suits the whole of this side of the building. Just look at the chimney and the white lean-to extension - it looks like part of a cottage has been stuck on the side of the church! But, as I said on my earlier post about the church, these rustic qualities are ones that I find quite attractive. On my previous visits to this church I'd never been able to get inside; it was always locked. On our recent visit the door was open and we had a look round. Truth be told it's not a very attractive interior; the remains of the arcade is the most interesting feature. The visitors' book dates back to the 1960s, and as my wife glanced through it she noted that entries in that decade and subsequently were not very numerous: presumably an indication that the building was rarely open. Perhaps we were fortunate to find it unlocked, or maybe it was because we visited on a Sunday.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 32mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/250 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.00 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Today's photograph was taken on the same day as my other black and white shot of Bonby church that I posted recently. It shows the the north side of the building and illustrates something I've discussed elsewhere in this blog, namely how medieval churches were enlarged by adding aisles.

The outline of arcade arches on the nave wall above shows that there was once an aisle attached to the building. It was probably required to accommodate a growing congregation. It may have been added to the original, small aisleless church by knocking out arch-shaped openings in the nave wall and replacing the remaining supporting walling with columns. Of course, when the aisle was added the windows had to be re-positioned (or new ones made) for the new aisle wall that was now farther from the middle of the nave. Sometimes the wall that was turned into an arcade was increased in height and windows were cut through the new, higher section, to shine light into the centre of the church. This solution involved raising the height of the nave roof. I don't know precisely why and how Bonby's aisle was fitted to the original church but it's very clear that at a later date it either became an expensive luxury that a decline in the size of the congregation rendered superfluous; or it fell down; or it became unsafe and was pulled down. Whatever the reason, every expense was spared in restoring the original nave wall. The arches and columns were left in place and simply filled with masonry. I wouldn't be surprised if the aisle windows were re-used too. The architectural effect is inelegant but interesting.

In fact, that description suits the whole of this side of the building. Just look at the chimney and the white lean-to extension - it looks like part of a cottage has been stuck on the side of the church! But, as I said on my earlier post about the church, these rustic qualities are ones that I find quite attractive. On my previous visits to this church I'd never been able to get inside; it was always locked. On our recent visit the door was open and we had a look round. Truth be told it's not a very attractive interior; the remains of the arcade is the most interesting feature. The visitors' book dates back to the 1960s, and as my wife glanced through it she noted that entries in that decade and subsequently were not very numerous: presumably an indication that the building was rarely open. Perhaps we were fortunate to find it unlocked, or maybe it was because we visited on a Sunday.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 32mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/250 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.00 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, August 09, 2013

The accommodating Comma

click photo to enlarge

The Big Butterfly Count is currently underway in the UK. This year it is running from 20th July to 11th August. An annual event organised by Butterfly Conservation, it enlists volunteers to count the species and number of butterflies on a bright or sunny day, in any location, over a period of 15 minutes. Results are collected and collated and help to give a picture of the relative health of the country's butterfly populations.

I recently consulted last year's results to find out the status of the Comma that I'd been photographing, at my wife's request, in our garden. Last year's wet summer produced somewhat atypical results with the Meadow Brown the runaway winner in terms of numbers. The commonest butterflies in my garden this year are (with last year's placings in brackets) Small White (4), Large White (5), Peacock (16), Red Admiral (11) and Small Tortoiseshell (10). However, we see several more including the Brimstone, Wall, Painted Lady and others. The Comma also turns up now and again. Last year it was the 12th commonest species nationwide.

The Comma is named after the small white comma-like mark on the underside of its wings. It's an attractive butterfly with its orange and black markings and ragged edged wings. A characteristic that endears it to me as a photographer is the fact that it scares much less easily than, say, Peacocks and Red Admirals, when the camera lens approaches it. I took today's shot with a 100mm macro lens that had a hood mounted on the end of it. The butterfly tolerated the edge of the hood a matter of 10 centimetres or less from it, and that when the camera was mounted on a bright silver tripod. A very accommodating butterfly in that respect.

The Comma is named after the small white comma-like mark on the underside of its wings. It's an attractive butterfly with its orange and black markings and ragged edged wings. A characteristic that endears it to me as a photographer is the fact that it scares much less easily than, say, Peacocks and Red Admirals, when the camera lens approaches it. I took today's shot with a 100mm macro lens that had a hood mounted on the end of it. The butterfly tolerated the edge of the hood a matter of 10 centimetres or less from it, and that when the camera was mounted on a bright silver tripod. A very accommodating butterfly in that respect.

Less accommodating in its choice of flowers however. A bright orange Comma butterfly on a pink and orange Coneflower (Echinacea) with green leaves in the background makes for an eye-watering colour combination. They would become my number one butterfly in all respects if they'd feed on one of our dusky blue flowers so I could compose photographs with colours more to my liking!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 100mm macro

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/80 sec

ISO: 200

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: Off

The Big Butterfly Count is currently underway in the UK. This year it is running from 20th July to 11th August. An annual event organised by Butterfly Conservation, it enlists volunteers to count the species and number of butterflies on a bright or sunny day, in any location, over a period of 15 minutes. Results are collected and collated and help to give a picture of the relative health of the country's butterfly populations.

I recently consulted last year's results to find out the status of the Comma that I'd been photographing, at my wife's request, in our garden. Last year's wet summer produced somewhat atypical results with the Meadow Brown the runaway winner in terms of numbers. The commonest butterflies in my garden this year are (with last year's placings in brackets) Small White (4), Large White (5), Peacock (16), Red Admiral (11) and Small Tortoiseshell (10). However, we see several more including the Brimstone, Wall, Painted Lady and others. The Comma also turns up now and again. Last year it was the 12th commonest species nationwide.

The Comma is named after the small white comma-like mark on the underside of its wings. It's an attractive butterfly with its orange and black markings and ragged edged wings. A characteristic that endears it to me as a photographer is the fact that it scares much less easily than, say, Peacocks and Red Admirals, when the camera lens approaches it. I took today's shot with a 100mm macro lens that had a hood mounted on the end of it. The butterfly tolerated the edge of the hood a matter of 10 centimetres or less from it, and that when the camera was mounted on a bright silver tripod. A very accommodating butterfly in that respect.

The Comma is named after the small white comma-like mark on the underside of its wings. It's an attractive butterfly with its orange and black markings and ragged edged wings. A characteristic that endears it to me as a photographer is the fact that it scares much less easily than, say, Peacocks and Red Admirals, when the camera lens approaches it. I took today's shot with a 100mm macro lens that had a hood mounted on the end of it. The butterfly tolerated the edge of the hood a matter of 10 centimetres or less from it, and that when the camera was mounted on a bright silver tripod. A very accommodating butterfly in that respect.Less accommodating in its choice of flowers however. A bright orange Comma butterfly on a pink and orange Coneflower (Echinacea) with green leaves in the background makes for an eye-watering colour combination. They would become my number one butterfly in all respects if they'd feed on one of our dusky blue flowers so I could compose photographs with colours more to my liking!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 100mm macro

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/80 sec

ISO: 200

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: Off

Wednesday, August 07, 2013

Bonby church 27 years later

click photo to enlarge

Anyone with an interest in English church architecture will be familiar with the main gazetteers and guides that document these buildings. All will know of the county volumes of the "Buildings of England" series by Nikolaus Pevsner (and others). Many will be familiar with John Betjeman's original or updated "Guide to English Parish Churches". And most will have an acquaintance with Simon Jenkins' "England's Thousand Best Churches". I have all these books and I list them here in order of preference, best first.

They all have their own take on listing and describing churches. Pevsner is completist and academic, Betjeman is brief, quirky and selective and Jenkins is more opinionated, historical, florid and his book has a more contentious title. Whose thousand best? Not mine, though he has many I would include. So how do I differ from Jenkins? Well, I have a liking for churches that have been knocked about a bit, that show their age, the ravages of time and the mark of successive builders. I can appreciate as much as the next man the big, richly ornamented, Grade 1 Listed, beautifully kept show-piece church. But, I can also appreciate the tumble-down, humble structure that needs a bit of maintenance, that can be found, with difficulty, surrounded by trees, at the end of a country lane: the sort of building that seems to grow out of the ground rather than look like it's been dropped in, scrubbed and polished, from on high.

Today's photograph shows a church that I liked the first time I saw it some time in the 1970s. It's a building that wouldn't even get on the long-list for Jenkins' best. St Andrew in the village of Bonby, Lincolnshire, is a mixture of work from the 1100s, 1200s and 1800s. The original stone has been replaced and reinforced by brick, and much of it shows its age. It must have always been a work in progress as people enlarged the church, made it smaller, renewed bits that fell down, patched walls, moved windows and blocked up doorways. After taking today's main photograph I searched out a shot of the church taken from a similar viewpoint that I remembered scanning from a slide last year. The original was taken in 1986 using an Olympus OM1n and a 135mm lens. I wanted to see if there had been any changes during the intervening 27 years. One jumped out at me immediately. The bottom two thirds of the east wall that was looking rough in 1986 is now rendered and painted white. But apart from that it was much the same low, squat, rustic building. Even the same dark red paint continues to be used on the drainpipes, gutters and door. I did notice one further difference: the churchyard grass is being kept a bit shorter!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 35mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/250 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Anyone with an interest in English church architecture will be familiar with the main gazetteers and guides that document these buildings. All will know of the county volumes of the "Buildings of England" series by Nikolaus Pevsner (and others). Many will be familiar with John Betjeman's original or updated "Guide to English Parish Churches". And most will have an acquaintance with Simon Jenkins' "England's Thousand Best Churches". I have all these books and I list them here in order of preference, best first.

They all have their own take on listing and describing churches. Pevsner is completist and academic, Betjeman is brief, quirky and selective and Jenkins is more opinionated, historical, florid and his book has a more contentious title. Whose thousand best? Not mine, though he has many I would include. So how do I differ from Jenkins? Well, I have a liking for churches that have been knocked about a bit, that show their age, the ravages of time and the mark of successive builders. I can appreciate as much as the next man the big, richly ornamented, Grade 1 Listed, beautifully kept show-piece church. But, I can also appreciate the tumble-down, humble structure that needs a bit of maintenance, that can be found, with difficulty, surrounded by trees, at the end of a country lane: the sort of building that seems to grow out of the ground rather than look like it's been dropped in, scrubbed and polished, from on high.

Today's photograph shows a church that I liked the first time I saw it some time in the 1970s. It's a building that wouldn't even get on the long-list for Jenkins' best. St Andrew in the village of Bonby, Lincolnshire, is a mixture of work from the 1100s, 1200s and 1800s. The original stone has been replaced and reinforced by brick, and much of it shows its age. It must have always been a work in progress as people enlarged the church, made it smaller, renewed bits that fell down, patched walls, moved windows and blocked up doorways. After taking today's main photograph I searched out a shot of the church taken from a similar viewpoint that I remembered scanning from a slide last year. The original was taken in 1986 using an Olympus OM1n and a 135mm lens. I wanted to see if there had been any changes during the intervening 27 years. One jumped out at me immediately. The bottom two thirds of the east wall that was looking rough in 1986 is now rendered and painted white. But apart from that it was much the same low, squat, rustic building. Even the same dark red paint continues to be used on the drainpipes, gutters and door. I did notice one further difference: the churchyard grass is being kept a bit shorter!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 35mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/250 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Monday, August 05, 2013

Volutes

click photo to enlarge

I first encountered the word "volute" when studying architectural history, in particular the Greek Ionic Order that is recognised by the large volutes that make up most of the ornamentation of the capital. The Corinthian and the Composite Orders have them too, on a lesser scale, but it is the Ionic that presents the architectural volute in all its beauty. In fact, the word "volute" comes from the Latin for "scroll", and looking at the spiral shape in the Ionic capital one can see how it might have derived from a parchment scroll seen end on.

Biologists use the word to describe the spiral shell of gastropods, in particular the genus Voluta. Violins and other stringed instruments often have a decorative volute at the top of the fingerboard near the tuning pegs, though this is also called a scroll. Guitar builders use "volute" to describe a thickening of the neck near the nut where one end of the truss rod is found, but this is an odd use of the word that doesn't respect its origins.

Today's photograph shows the wooden handrail of a Georgian staircase that terminates in a volute. It's not unusual to see a handrail of this period with a "turnout" whereby the straight line of the rail ends with a curve of approximately a quarter of a circle. However, if the client has money and pretensions then the architect can indulge himself with a volute, adding if he wants to go a step further, an ornamental finial on the centre. In the example above the expansion of the rail into a large, circular full-stop manages to be both elaborate and simple: perhaps elegant is the best word to describe it. As I processed this photograph, one that I took in the former Stamford Hotel in Stamford, Lincolnshire, it occurred to me that it might be a suitable candidate for a blue/sepia split-toning treatment. For more examples of this photographic treatment, one of that dates back to the days of chemical processing, see this promenade, this customer service centre or this House of Correction. For a view of the rest of this staircase see this post.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 14.8mm (40mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/25

ISO: 1600

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

I first encountered the word "volute" when studying architectural history, in particular the Greek Ionic Order that is recognised by the large volutes that make up most of the ornamentation of the capital. The Corinthian and the Composite Orders have them too, on a lesser scale, but it is the Ionic that presents the architectural volute in all its beauty. In fact, the word "volute" comes from the Latin for "scroll", and looking at the spiral shape in the Ionic capital one can see how it might have derived from a parchment scroll seen end on.

Biologists use the word to describe the spiral shell of gastropods, in particular the genus Voluta. Violins and other stringed instruments often have a decorative volute at the top of the fingerboard near the tuning pegs, though this is also called a scroll. Guitar builders use "volute" to describe a thickening of the neck near the nut where one end of the truss rod is found, but this is an odd use of the word that doesn't respect its origins.

Today's photograph shows the wooden handrail of a Georgian staircase that terminates in a volute. It's not unusual to see a handrail of this period with a "turnout" whereby the straight line of the rail ends with a curve of approximately a quarter of a circle. However, if the client has money and pretensions then the architect can indulge himself with a volute, adding if he wants to go a step further, an ornamental finial on the centre. In the example above the expansion of the rail into a large, circular full-stop manages to be both elaborate and simple: perhaps elegant is the best word to describe it. As I processed this photograph, one that I took in the former Stamford Hotel in Stamford, Lincolnshire, it occurred to me that it might be a suitable candidate for a blue/sepia split-toning treatment. For more examples of this photographic treatment, one of that dates back to the days of chemical processing, see this promenade, this customer service centre or this House of Correction. For a view of the rest of this staircase see this post.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 14.8mm (40mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/25

ISO: 1600

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Saturday, August 03, 2013

Old Triumph Mayflower

click photo to enlarge

I don't know much about cars, care even less, but I do know a wreck when I see one. And, as wrecks go, decaying and decrepit cars make interesting photographic subjects. The vehicle in today's post is one that I've passed a few times without taking a photograph. However, a couple of days ago the light seemed better, the vegetation was hanging down nicely against the darkness of its resting place, and I got out my compact camera and took a quick snap. The person I was walking with identified it for me as a Triumph Mayflower. It was a shape that I recognised from the 1950s but I'd have thought it was one of the Riley/Wolseley look-alikes.

A quick scan of the internet tells me that this particular model of car was manufactured from 1949-1953 by Triumph in both the UK and Australia, shortly after they'd been taken over by the Standard Motor Company. Apparently it was an attempt to build a small car with an up-market appeal, hence the traditional"sit-up-and-beg" styling and what were called at the time the "razor-edge" lines of the coachwork. It can't have been a great success because four years in production isn't very long and only 35,000 were manufactured. In fact, the only Triumphs I really remember from my childhood and youth were the Triumph Herald, the Vitesse, Spitfire the TR Series sports cars and the Stag - all later than the Mayflower, and many of them redolent of the "swinging sixties". I imagine this Mayflower has been bought as a restoration project. I wish its owner many happy hours sourcing wing mirrors, bumper over-riders etc and much satisfying, fulfilling work of rejuvenation.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 32.2mm (87mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f4.5

Shutter Speed: 1/100

ISO: 320

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

I don't know much about cars, care even less, but I do know a wreck when I see one. And, as wrecks go, decaying and decrepit cars make interesting photographic subjects. The vehicle in today's post is one that I've passed a few times without taking a photograph. However, a couple of days ago the light seemed better, the vegetation was hanging down nicely against the darkness of its resting place, and I got out my compact camera and took a quick snap. The person I was walking with identified it for me as a Triumph Mayflower. It was a shape that I recognised from the 1950s but I'd have thought it was one of the Riley/Wolseley look-alikes.

A quick scan of the internet tells me that this particular model of car was manufactured from 1949-1953 by Triumph in both the UK and Australia, shortly after they'd been taken over by the Standard Motor Company. Apparently it was an attempt to build a small car with an up-market appeal, hence the traditional"sit-up-and-beg" styling and what were called at the time the "razor-edge" lines of the coachwork. It can't have been a great success because four years in production isn't very long and only 35,000 were manufactured. In fact, the only Triumphs I really remember from my childhood and youth were the Triumph Herald, the Vitesse, Spitfire the TR Series sports cars and the Stag - all later than the Mayflower, and many of them redolent of the "swinging sixties". I imagine this Mayflower has been bought as a restoration project. I wish its owner many happy hours sourcing wing mirrors, bumper over-riders etc and much satisfying, fulfilling work of rejuvenation.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 32.2mm (87mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f4.5

Shutter Speed: 1/100

ISO: 320

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Thursday, August 01, 2013

Mundane photographic subjects

click photo to enlarge

Some of my best photographs feature the most mundane subjects. This comes as no surprise to me because, having an interest in art and painting, I long ago observed that the same is true of many works that I like. What it does mean, however, is that it isn't especially easy to find such subjects because you don't usually plan for them in the way that you might for a landscape, portrait, architecture or other branches of photography. What often happens is that during the course of doing something entirely unrelated to photography, you notice a composition or item that looks like it might make a shot and you point your camera at it. Such an approach relies on you having a camera with you at the time and that's where a pocketable compact camera is so valuable.

Today's photograph was taken while we were gathering blackcurrants at the house of some friends. Many people in rural communities swap and share garden produce when they have a glut that is beyond their capacity to eat, store, preserve or freeze. It's a sociable and sensible thing to do. Having filled a couple of containers we were sitting at a textured glass table below a green parasol enjoying a soft drink when this composition caught my eye. Glasses and bottles have been the stock in trade of painters of still life for centuries, and the simple qualities of form, colour, shape, reflection and transparency that these objects presented to me had something of a painting about them. Perhaps it was the way the tinted, textured, opaque glass of the table top looked like it was composed of brush strokes. Or maybe it was the way the same surface turned the clouds into what looked like painted representations of clouds rather than reflections. Whatever the reason, I took my shot and I'm happy to say its modest, unaffected qualities please me more than most of the images I've posted on the blog in recent months.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 21.5mm (58mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/250

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: -0.7 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Some of my best photographs feature the most mundane subjects. This comes as no surprise to me because, having an interest in art and painting, I long ago observed that the same is true of many works that I like. What it does mean, however, is that it isn't especially easy to find such subjects because you don't usually plan for them in the way that you might for a landscape, portrait, architecture or other branches of photography. What often happens is that during the course of doing something entirely unrelated to photography, you notice a composition or item that looks like it might make a shot and you point your camera at it. Such an approach relies on you having a camera with you at the time and that's where a pocketable compact camera is so valuable.

Today's photograph was taken while we were gathering blackcurrants at the house of some friends. Many people in rural communities swap and share garden produce when they have a glut that is beyond their capacity to eat, store, preserve or freeze. It's a sociable and sensible thing to do. Having filled a couple of containers we were sitting at a textured glass table below a green parasol enjoying a soft drink when this composition caught my eye. Glasses and bottles have been the stock in trade of painters of still life for centuries, and the simple qualities of form, colour, shape, reflection and transparency that these objects presented to me had something of a painting about them. Perhaps it was the way the tinted, textured, opaque glass of the table top looked like it was composed of brush strokes. Or maybe it was the way the same surface turned the clouds into what looked like painted representations of clouds rather than reflections. Whatever the reason, I took my shot and I'm happy to say its modest, unaffected qualities please me more than most of the images I've posted on the blog in recent months.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 21.5mm (58mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6