click photo to enlarge

Like most Lincolnshire towns Spalding has many buildings of architectural and historic importance. Anyone with an eye for architectural history cannot fail to find a walk around the centre of the town and its periphery a rewarding experience. A medieval church, the remains of abbey buildings, old inns, warehouses, Georgian terraces, individual houses and Sir George Gilbert Scott's last church, are just a few of the delights the informed visitor will find. However, though the eighteenth century is very well represented the seventeenth century is less so. This is true in much of Britain, of course, but in Lincolnshire the relative prosperity of the eighteenth century meant that many buildings of a century earlier were either replaced or, very often, re-modelled. The pitch of a roof, a stepped wall, a painted over piece of structural timber or a centrally placed chimney (as opposed to later gable chimneys) are just some of the clues that an older building lurks beneath an eighteenth century facelift.

But, on Albion Street, a route that parallels the River Welland on the north-eastern edge of the town centre, an early seventeenth century house that received little in the way of "modernising" can be found standing behind its small, formal, front garden of geometric, dwarf box hedges. It was built in the early 1600s on what has been described as a "flattened H plan". "Willesby" has characteristic English bond brick walls with alternating courses of headers and stretchers. The mullioned two, three and four-light windows are framed in dressed stone. Stone is also used for the doorway (a Victorian restoration), the lowest courses of the walls, for the quoins that unusually don't extend the full height of wall corners, and for the "kneelers" and gable coping. A plain tile roof tops the building. It is a well-presented house that illustrates a type that can be found in many parts of eastern England in both town and country.

In summer the main façade is clothed with the greenery of the climbers and surrounding shrubs. On the dull, end of March day of my photograph, however, the lateness of this year's spring meant that much was still visible to the curious passer-by.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 20.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f4

Shutter Speed: 1/320

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: -0.3 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Pages

▼

Sunday, March 31, 2013

Friday, March 29, 2013

Billingborough church at night

click photo to enlarge

Driving in the dark over the low hills between Folkingham and Billingborough the other evening, the church tower of St Andrew came into view. It caught my eye as its illumination made it glow like a golden lighthouse, a beacon for travellers heading down onto the Fens. As we drew into the village the tall, fourteenth century tower and spire seemed to be brighter still against the mottled sky, and appeared to be in competition with the moon to see which could best catch the eye of passers-by. It was a contest that, on this particular night, the church was winning. However, the effect of the full moon on the broken cloud was so pleasing we parked up and had a brisk walk to find some photographs that included these two sources of light. It was also, I thought, a good opportunity to try my new compact camera's iAuto+ mode, a setting whereby it takes several shots very rapidly and then merges them to make a single image with reduced noise and motion blur.

Of the cluster of photographs I took the main one is the image I like best. It was taken through the gateway of Billingborough Hall, a large house built in 1620 and modified in the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This building is now a care home for the elderly. For my purposes it provided not only more lights in the form of lit windows to punctuate the darkness, but roof and chimney silhouettes and foreground illumination spilling onto the drive from a nearby streetlight. The tower of St Andrew glows in the photograph in just the ethereal way it did at the time, a dominating presence now at night just as it must always have been in the village during the day.

There is a pond near the west end of the church so we walked round to see if there was a photograph to be had that included a reflection of the church in the water. I came away with the smaller photograph and a few failed shots that included sleeping ducks on the pond's island. Billingborough church is an imposing building that is a fine exclamation mark in its village setting. It's a subject I've photographed several times - see, for example, this shot with the nearby Church Farm. I've photographed the pond before too.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: iAuto+

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f1.8

Shutter Speed: 1/8

ISO: 2000

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Driving in the dark over the low hills between Folkingham and Billingborough the other evening, the church tower of St Andrew came into view. It caught my eye as its illumination made it glow like a golden lighthouse, a beacon for travellers heading down onto the Fens. As we drew into the village the tall, fourteenth century tower and spire seemed to be brighter still against the mottled sky, and appeared to be in competition with the moon to see which could best catch the eye of passers-by. It was a contest that, on this particular night, the church was winning. However, the effect of the full moon on the broken cloud was so pleasing we parked up and had a brisk walk to find some photographs that included these two sources of light. It was also, I thought, a good opportunity to try my new compact camera's iAuto+ mode, a setting whereby it takes several shots very rapidly and then merges them to make a single image with reduced noise and motion blur.

Of the cluster of photographs I took the main one is the image I like best. It was taken through the gateway of Billingborough Hall, a large house built in 1620 and modified in the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This building is now a care home for the elderly. For my purposes it provided not only more lights in the form of lit windows to punctuate the darkness, but roof and chimney silhouettes and foreground illumination spilling onto the drive from a nearby streetlight. The tower of St Andrew glows in the photograph in just the ethereal way it did at the time, a dominating presence now at night just as it must always have been in the village during the day.

There is a pond near the west end of the church so we walked round to see if there was a photograph to be had that included a reflection of the church in the water. I came away with the smaller photograph and a few failed shots that included sleeping ducks on the pond's island. Billingborough church is an imposing building that is a fine exclamation mark in its village setting. It's a subject I've photographed several times - see, for example, this shot with the nearby Church Farm. I've photographed the pond before too.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: iAuto+

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f1.8

Shutter Speed: 1/8

ISO: 2000

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, March 27, 2013

Fishing platforms and films noir

click photo to enlarge

I think I watch too many films noir. Or perhaps it's the spate of TV police dramas of Danish origin that BBC 4 has shown in the past couple of years: all night time sets, rain, winter skies, dour expressions and dour locations. Why? Well, when I brought this photograph up on the computer screen I imagined it being a scene in such a film, the camera pulling back to show a couple of police cars, lights flashing, on the pond bank, detectives exchanging theories and a diver in a wet suit about to enter the water in search of a body.

Of course, the actual scene when I took the shot was nothing like that. I'd taken a few steps from a path by the River Slea to look at the fishing pond among the reeds with its old wooden platforms. Other people were enjoying the fresh air and the water-side walk. Cars were passing a hundred yards or so away on a busy, built-up road, and mallards and moorhens were deciding whether to bother with nest building or to wait for an improvement in the weather.

Photographs are like that. People take preconceptions, misconceptions and ideas to the viewing experience and see in an image something that isn't there for other viewers. That's not too surprising. But it is somewhat odd that the person who took the photograph, viewing his own image later on the same day that he took the shot, and knowing what the context was, should do the same.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 22mm (59mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f4.5

Shutter Speed: 1/100

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

I think I watch too many films noir. Or perhaps it's the spate of TV police dramas of Danish origin that BBC 4 has shown in the past couple of years: all night time sets, rain, winter skies, dour expressions and dour locations. Why? Well, when I brought this photograph up on the computer screen I imagined it being a scene in such a film, the camera pulling back to show a couple of police cars, lights flashing, on the pond bank, detectives exchanging theories and a diver in a wet suit about to enter the water in search of a body.

Of course, the actual scene when I took the shot was nothing like that. I'd taken a few steps from a path by the River Slea to look at the fishing pond among the reeds with its old wooden platforms. Other people were enjoying the fresh air and the water-side walk. Cars were passing a hundred yards or so away on a busy, built-up road, and mallards and moorhens were deciding whether to bother with nest building or to wait for an improvement in the weather.

Photographs are like that. People take preconceptions, misconceptions and ideas to the viewing experience and see in an image something that isn't there for other viewers. That's not too surprising. But it is somewhat odd that the person who took the photograph, viewing his own image later on the same day that he took the shot, and knowing what the context was, should do the same.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 22mm (59mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f4.5

Shutter Speed: 1/100

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Monday, March 25, 2013

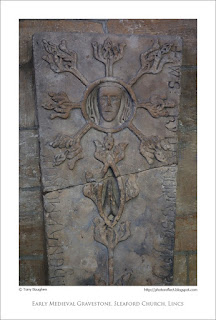

Early medieval gravestones

The gravestones, tomb slabs and funerary monuments of English churches range in date from the twelfth century to the present day. Each one seeks to remember or exalt the deceased. Few of the older ones are in the position where they were first placed and many of these have been damaged by incident, accident or design. Sometimes they have been crudely cut so that a later architectural embellishment could be effected. Often Protestant zealots of the Reformation or later have taken their hammers to them, knocking off noses, limbs and any other easily removed projection as they sought to demonstrate their hatred of "idolatry". However, despite the vicissitudes of time, many have survived, largely intact, bequeathing to later generations information about the sculptural abilities and stylistic preferences of earlier times.

The oldest such monuments were often lids for stone coffins, decorated by a foliate cross or lines of stylised leaves. These usually date from the 1100s. Also found at this time, and a little later, are stone coffin lids with circles, quatrefoils or almond-shaped holes within which are carvings of parts of the body that is being commemorated. Today's photographs show an example of just such a gravestone that can be seen in the church of St Denys at Sleaford, Lincolnshire. The viewer is invited to look, asit were, through "holes" in the surface of the lid, at the face, hands held in prayer and feet of a woman. The inscription around the edge tells us who she is. It says, "Ye who here pass by, for the soul of Yvette pray, who was the honoured wife of William of Rauceby on whose soul may god have mercy". These holes are incorporated in a leafy cross that decorates the surface of the coffin-shaped stone. It is likely to date from the 1100s. Despite being broken in two and now being fixed to the wall rather than laying flat on or under the ground, the stonework is still clear and the writing remains legible, a testament to the durable qualities that the sculptor conferred on the piece and to the care with which the church has been maintained for the past thousand or so years.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: iAuto+

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f1.8

Shutter Speed: 1/30

ISO: 400

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Saturday, March 23, 2013

Glass sculpture

click photo to enlarge

Glass has many qualities that fascinate me: its ability to reflect, to distort, to transmit light through its structure, its hardness and smoothness, even its fragility. In recent years I've realised that glass has always intrigued me. Even back in my childhood I loved to look into mirrors, glass marbles, prisms, cheap jewellery or cut glass decanters to see how they distorted reality. But it's only in the past fifteen or so years, as I've expanded the range of my photography, that I've realised the depth of my interest. Now I rarely miss an opportunity to snap a good reflection, a distortion or any other kind of interesting manifestation in glass.

When I go to the National Centre for Craft and Design in Sleaford I find that its always the glass exhibits for sale in their shop that I look at first. I can't say I've bought a lot of "art" glass, but we did buy a couple of rather fine bowls a few years ago, one of which has made an appearance on the blog. Consequently, when we recently made one of our regular trips to Sleaford to take in the current exhibition I was delighted to find that it featured the work of someone who worked in glass. Luke Jerram had pieces from three of his major series on display: Radiometer Chandeliers, Glass Microbiology and Rotated Data Sculpture. It was very refreshing to find that these titles are very clear descriptions of the work rather than the usual opaque artspeak. Of the three types of glass work it was the forms drawn from the world of viruses, bacteria and microbiology that I enjoyed most. To see structures inspired by the microscopic forms that can only be seen under powerful magnification, that are rendered large, in beautifully formed glass and lit by powerful lamps was marvellous. So much so that I took a couple of shots with my pocket camera. Today's photograph is a detail of one of the larger pieces.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: iAuto

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/250

ISO: 160

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Glass has many qualities that fascinate me: its ability to reflect, to distort, to transmit light through its structure, its hardness and smoothness, even its fragility. In recent years I've realised that glass has always intrigued me. Even back in my childhood I loved to look into mirrors, glass marbles, prisms, cheap jewellery or cut glass decanters to see how they distorted reality. But it's only in the past fifteen or so years, as I've expanded the range of my photography, that I've realised the depth of my interest. Now I rarely miss an opportunity to snap a good reflection, a distortion or any other kind of interesting manifestation in glass.

When I go to the National Centre for Craft and Design in Sleaford I find that its always the glass exhibits for sale in their shop that I look at first. I can't say I've bought a lot of "art" glass, but we did buy a couple of rather fine bowls a few years ago, one of which has made an appearance on the blog. Consequently, when we recently made one of our regular trips to Sleaford to take in the current exhibition I was delighted to find that it featured the work of someone who worked in glass. Luke Jerram had pieces from three of his major series on display: Radiometer Chandeliers, Glass Microbiology and Rotated Data Sculpture. It was very refreshing to find that these titles are very clear descriptions of the work rather than the usual opaque artspeak. Of the three types of glass work it was the forms drawn from the world of viruses, bacteria and microbiology that I enjoyed most. To see structures inspired by the microscopic forms that can only be seen under powerful magnification, that are rendered large, in beautifully formed glass and lit by powerful lamps was marvellous. So much so that I took a couple of shots with my pocket camera. Today's photograph is a detail of one of the larger pieces.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: iAuto

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/250

ISO: 160

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Thursday, March 21, 2013

The beauty and utility of feathers

click photo to enlarge

In the not too distant past the feathers of domestic birds such as hens, ducks and geese were highly prized. In fact, those of certain wild birds were too. I remember, as a teenager, watching one of my uncles use the blue wing feathers of a jay to make a fishing fly. He also used pheasant wings as a brush-like utensil to keep the hearth in front of an open fire clear of the ash and soot that fell from the logs, and the blue-green feathers of the mallard's speculum in the band of his hat.

Birds are no longer driven to the edge of extinction by the desire for feathers for fashionable clothing, but there is still a small market for items that use their insulating qualities. However, the downy feathers of geese and ducks used to be much more widely used for stuffing cushions, pillows and the eiderdowns that topped beds in cold weather. On the Furness peninsula and the Northumbrian coast the feathers of wild eider ducks were carefully "harvested" from nests for the purpose of filling this much-valued article of bedding. Elsewhere it was domestic breeds or wild mallard, teal, wigeon etc that were pressed into service. In the Fens of Lincolnshire and in other suitably watery areas such as the Norfolk Broads, the Cheshire meres or the Somerset Levels, purpose-made duck decoys were used to trap wild ducks. The birds were eaten and the feathers used as described above.

At the bottom of the list of desirable species from which to gather feathers was the domestic hen. Their feathers were used, but not so prized as those of the eider or geese. The other day I photographed one of my neighbour's hens, a bird that has what look to be very soft, grey feathers that are quite subtly but attractively marked. I've always been fascinated by the beauty of birds' feathers and collected them as a child. My "collecting" these days is done with a camera. Today's photograph is, I think, the fourth photograph of beautifully marked hens feathers that I've posted on the blog. One shows two images of contrasting cockerel feathers. A second has bright orange feathers contrasting with iridescent green, and the final example illustrates the rich, but more subdued colours that some cockerels display. I've also posted one featuring teal feathers.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Auto

Focal Length: 37.1mm (100mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f4.9

Shutter Speed: 1/125

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

In the not too distant past the feathers of domestic birds such as hens, ducks and geese were highly prized. In fact, those of certain wild birds were too. I remember, as a teenager, watching one of my uncles use the blue wing feathers of a jay to make a fishing fly. He also used pheasant wings as a brush-like utensil to keep the hearth in front of an open fire clear of the ash and soot that fell from the logs, and the blue-green feathers of the mallard's speculum in the band of his hat.

Birds are no longer driven to the edge of extinction by the desire for feathers for fashionable clothing, but there is still a small market for items that use their insulating qualities. However, the downy feathers of geese and ducks used to be much more widely used for stuffing cushions, pillows and the eiderdowns that topped beds in cold weather. On the Furness peninsula and the Northumbrian coast the feathers of wild eider ducks were carefully "harvested" from nests for the purpose of filling this much-valued article of bedding. Elsewhere it was domestic breeds or wild mallard, teal, wigeon etc that were pressed into service. In the Fens of Lincolnshire and in other suitably watery areas such as the Norfolk Broads, the Cheshire meres or the Somerset Levels, purpose-made duck decoys were used to trap wild ducks. The birds were eaten and the feathers used as described above.

At the bottom of the list of desirable species from which to gather feathers was the domestic hen. Their feathers were used, but not so prized as those of the eider or geese. The other day I photographed one of my neighbour's hens, a bird that has what look to be very soft, grey feathers that are quite subtly but attractively marked. I've always been fascinated by the beauty of birds' feathers and collected them as a child. My "collecting" these days is done with a camera. Today's photograph is, I think, the fourth photograph of beautifully marked hens feathers that I've posted on the blog. One shows two images of contrasting cockerel feathers. A second has bright orange feathers contrasting with iridescent green, and the final example illustrates the rich, but more subdued colours that some cockerels display. I've also posted one featuring teal feathers.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Auto

Focal Length: 37.1mm (100mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f4.9

Shutter Speed: 1/125

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Tuesday, March 19, 2013

Living in the past?

click photo to enlarge

Getting older gives you perspective and with perspective comes humility. At least that's what happens for many people. As teenagers people are often self-absorbed, the centre of their own little universe about which everything revolves. Then, as we age, start a family and shoulder the attendant responsibilities of partner, children and work, the inward focus continues. It is less marked than in our younger years because the compass of our lives extends, but it is there nonetheless. Often it's not until our offspring have departed the nest that people experience sufficient time to pause and reflect in a more considered way about the three big questions in life - "Who are we, whence come we, whither go we" (as Gauguin put it). And with retirement the viewpoint and perspective that age brings throws these questions into sharper relief.

It's natural at that point to reflect on yourself as a person. One thing that many older people conclude (I am one of them) is that the extent to which we are like other people is much greater than the extent to which we are different from them. This is something that teenagers find hard to accept and which might account for the sometimes extraordinary lengths they go to in order to dress and behave like their friends. It's also natural, with greater age, to look back at your life, to consider how it was different from today and to make value judgements about whether it was better or not. This, as I've said elsewhere in the blog, is a path fraught with dangers and delusions. And then there's the rather less problematic fondness that can grow for the objects and habits of our past - the artefacts, vehicles, ways of living etc that we experienced as our younger selves.

I was thinking about this the other morning as I watched a railway artist paint a picture of the locomotive, "Mallard". This was the LNER Class A4 steam engine designed by Sir Nigel Gresley that in 1938 achieved the world speed record of 125.88 mph (202.58 km/h) for a steam-powered locomotives, a record that still stands today. The artist was plying his trade at an exhibition of transport models - trains, boats etc - and must have been painting this particular subject with an eye to the 75th anniversary of that record-breaking run - it falls on 3rd July of this year - and the sort of person who was a potential customer. On looking round it was clear that the great majority of exhibitors and most of the visitors were aged sixty or older, that it wasn't only the fact that they had the time to indulge in their hobby that caused them to pick this one, it was also their age. It seemed to me that a sort of second childhood was upon them - and they were thoroughly enjoying it!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 28mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed:1/30

ISO: 1000

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: N/A

Getting older gives you perspective and with perspective comes humility. At least that's what happens for many people. As teenagers people are often self-absorbed, the centre of their own little universe about which everything revolves. Then, as we age, start a family and shoulder the attendant responsibilities of partner, children and work, the inward focus continues. It is less marked than in our younger years because the compass of our lives extends, but it is there nonetheless. Often it's not until our offspring have departed the nest that people experience sufficient time to pause and reflect in a more considered way about the three big questions in life - "Who are we, whence come we, whither go we" (as Gauguin put it). And with retirement the viewpoint and perspective that age brings throws these questions into sharper relief.

It's natural at that point to reflect on yourself as a person. One thing that many older people conclude (I am one of them) is that the extent to which we are like other people is much greater than the extent to which we are different from them. This is something that teenagers find hard to accept and which might account for the sometimes extraordinary lengths they go to in order to dress and behave like their friends. It's also natural, with greater age, to look back at your life, to consider how it was different from today and to make value judgements about whether it was better or not. This, as I've said elsewhere in the blog, is a path fraught with dangers and delusions. And then there's the rather less problematic fondness that can grow for the objects and habits of our past - the artefacts, vehicles, ways of living etc that we experienced as our younger selves.

I was thinking about this the other morning as I watched a railway artist paint a picture of the locomotive, "Mallard". This was the LNER Class A4 steam engine designed by Sir Nigel Gresley that in 1938 achieved the world speed record of 125.88 mph (202.58 km/h) for a steam-powered locomotives, a record that still stands today. The artist was plying his trade at an exhibition of transport models - trains, boats etc - and must have been painting this particular subject with an eye to the 75th anniversary of that record-breaking run - it falls on 3rd July of this year - and the sort of person who was a potential customer. On looking round it was clear that the great majority of exhibitors and most of the visitors were aged sixty or older, that it wasn't only the fact that they had the time to indulge in their hobby that caused them to pick this one, it was also their age. It seemed to me that a sort of second childhood was upon them - and they were thoroughly enjoying it!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 28mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed:1/30

ISO: 1000

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: N/A

Sunday, March 17, 2013

Kinema in the Woods

click photo to enlarge

The charming and very unusual Kinema* in the Woods at Woodhall Spa, Lincolnshire, showed its first film in 1922. The cinema had been built from the remains of the sports pavilion of the Victoria Hotel that burned down in 1920. Programming on that opening evening featured a Charlie Chaplin film as the scheduled film didn't arrive in time. Most of the seats were the traditional "tip-up" variety but the front six rows were deck chairs, a feature that continued until as late as 1953.

The cinema is unusual in using rear projection. This is necessary due to the low roof timbers that would impede front projection. In the main auditorium (Screen One) the film is projected from behind the screen onto a mirror that flips the image before it goes on to the back of the screen. The building's current owners believe it is the only cinema in the UK still using this method of projection. In 1978 two electronically controlled sound projectors replaced the single sound projector that was first installed in 1928. A few years later in 1984, in a move that harked back to an earlier age in cinema and which underlined the owner's desire to make a visit to the Kinema in the Woods a real event, a Compton Kinestra organ was installed. This has a console with an ornate design in red and gold laquer. It is regularly played by the cinema's resident organist. In 1994 a second auditorium with the name "Kinema Too" was opened.

The cinema is open every evening of the week with weekend matinees. I took my photograph after an evening appointment in Woodhall Spa. Before my journey home I drove through the woods to the cinema in the hope that it was open and lit up for the evening and found it busy and surrounded by cars. The smaller photograph is a shot of the writing, illumination and advertising on the main facade. On the central gable it says,"England's Unique Cinema, Films Nightly. Down Memory Lane: The Kinema's Nostalgia Show - Featuring the Mighty Compton Organ".

* The spelling "kinema" rather than the usual "cinema" was much more common in the early days of movie film. The "k" comes from its derivation from the original Greek word for "motion". Words such as kinematographic, kinematoscope and kinema were coined as movies took off, but in time were replaced by versions beginning with "c". The original cinematographers would have been familiar with the word, "kinematics" that was used in the nineteenth century (from 1840) to describe the science of pure motion.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f2.8

Shutter Speed: 1/15

ISO: 800

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

The charming and very unusual Kinema* in the Woods at Woodhall Spa, Lincolnshire, showed its first film in 1922. The cinema had been built from the remains of the sports pavilion of the Victoria Hotel that burned down in 1920. Programming on that opening evening featured a Charlie Chaplin film as the scheduled film didn't arrive in time. Most of the seats were the traditional "tip-up" variety but the front six rows were deck chairs, a feature that continued until as late as 1953.

The cinema is unusual in using rear projection. This is necessary due to the low roof timbers that would impede front projection. In the main auditorium (Screen One) the film is projected from behind the screen onto a mirror that flips the image before it goes on to the back of the screen. The building's current owners believe it is the only cinema in the UK still using this method of projection. In 1978 two electronically controlled sound projectors replaced the single sound projector that was first installed in 1928. A few years later in 1984, in a move that harked back to an earlier age in cinema and which underlined the owner's desire to make a visit to the Kinema in the Woods a real event, a Compton Kinestra organ was installed. This has a console with an ornate design in red and gold laquer. It is regularly played by the cinema's resident organist. In 1994 a second auditorium with the name "Kinema Too" was opened.

The cinema is open every evening of the week with weekend matinees. I took my photograph after an evening appointment in Woodhall Spa. Before my journey home I drove through the woods to the cinema in the hope that it was open and lit up for the evening and found it busy and surrounded by cars. The smaller photograph is a shot of the writing, illumination and advertising on the main facade. On the central gable it says,"England's Unique Cinema, Films Nightly. Down Memory Lane: The Kinema's Nostalgia Show - Featuring the Mighty Compton Organ".

* The spelling "kinema" rather than the usual "cinema" was much more common in the early days of movie film. The "k" comes from its derivation from the original Greek word for "motion". Words such as kinematographic, kinematoscope and kinema were coined as movies took off, but in time were replaced by versions beginning with "c". The original cinematographers would have been familiar with the word, "kinematics" that was used in the nineteenth century (from 1840) to describe the science of pure motion.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f2.8

Shutter Speed: 1/15

ISO: 800

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, March 15, 2013

Who knows where the time goes?

click photo to enlarge

I turned off comments in January and February because I was rather busier than usual and I found that I couldn't devote as much time to the blog as I usually do. Then, at the beginning of March, feeling that things were easing off a little, I turned them back on. That proved to be the wrong thing to do! Things are busier than they were earlier in the year! In fact, the other evening when I glanced at the clock and noticed that a couple of hours had passed in what seemed like a few minutes, I found myself reciting the title of the Sandy Denny song, one that I recall her singing on the Fairport Convention album, "Unhalfbricking", of 1969. "Who Knows Where The Time Goes" will be known by many through Judy Collins' version. I like them both, but of the two singers' voices Sandy Denny's is the one I prefer: her version of "She Moves Through The Fair" (on the album "What We Did On Our Holidays") is one of my favourite songs by a female vocalist.

All of which has little to do with today's photograph. It's an exercise in applying natural lighting and burning that I did a while ago. I'm not a fan of flash, though I do use it occasionally when I try to make it mimic natural light. Here I wanted "Caravaggioesque" lighting i.e very directional light with deep shadows. To achieve it I arranged some curtains to so that a shaft of light from the window fell adjacent to darker areas in a room What better to use as the subject in this exercise in trying to achieve the lighting that one of the Renaissance's greatest painters made his signature effect than the subject used by countless other painters down the centuries - a simple bowl of fruit. In fact - and here I'm consciously trying to establish a link with the title of today's post - a timeless subject. I post it with an apology. This photograph was one of my rejects. I've run out of fresh photographs due to having no time to pursue them. So, if my posting rate declines further you'll know the reason why.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 100mm macro

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/15 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

I turned off comments in January and February because I was rather busier than usual and I found that I couldn't devote as much time to the blog as I usually do. Then, at the beginning of March, feeling that things were easing off a little, I turned them back on. That proved to be the wrong thing to do! Things are busier than they were earlier in the year! In fact, the other evening when I glanced at the clock and noticed that a couple of hours had passed in what seemed like a few minutes, I found myself reciting the title of the Sandy Denny song, one that I recall her singing on the Fairport Convention album, "Unhalfbricking", of 1969. "Who Knows Where The Time Goes" will be known by many through Judy Collins' version. I like them both, but of the two singers' voices Sandy Denny's is the one I prefer: her version of "She Moves Through The Fair" (on the album "What We Did On Our Holidays") is one of my favourite songs by a female vocalist.

All of which has little to do with today's photograph. It's an exercise in applying natural lighting and burning that I did a while ago. I'm not a fan of flash, though I do use it occasionally when I try to make it mimic natural light. Here I wanted "Caravaggioesque" lighting i.e very directional light with deep shadows. To achieve it I arranged some curtains to so that a shaft of light from the window fell adjacent to darker areas in a room What better to use as the subject in this exercise in trying to achieve the lighting that one of the Renaissance's greatest painters made his signature effect than the subject used by countless other painters down the centuries - a simple bowl of fruit. In fact - and here I'm consciously trying to establish a link with the title of today's post - a timeless subject. I post it with an apology. This photograph was one of my rejects. I've run out of fresh photographs due to having no time to pursue them. So, if my posting rate declines further you'll know the reason why.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 100mm macro

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/15 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

Concrete pantiles

click photo to enlarge

The first flat clay tiles (plain tiles) in England were probably those introduced by the Romans. They manufactured them here too and examples can still be found in the cities, towns and villas that were built during their time in these islands. Medieval masons found them and incorporated some in their walling, though they increasingly manufactured their own plain tiles as a fire-proof replacement for thatch.The pantile with its "S" shaped curve was introduced into England from the Low Countries in the seventeenth century. Its name derives from the old Dutch "dakpan" (roof pan) and the German "pfannenziegel" (pantile). They quickly became popular in the eastern counties of our country where thatch predominated and roofing stone was scarce. In these areas, by the eighteenth century, pantiles were the roof covering of choice for anyone with a reasonable amount of money. Today they are still manufactured, still used for roofs and there are still examples from the earliest times to be seen on roofs, continuing to protect the buildings that often date from centuries ago.

Twentieth century manufacturers of concrete tiles weren't slow to realise the beauty of pantiles and the ease with which they are laid, overlapping each other and hooked over wooden battens. My garage, a modern structure, is roofed with a variant of this design and the tiles have weathered to a quite pleasing dark, mottled hue that in every aspect, except south-facing, grows a patina of moss and lichen. In spring and summer the low parts of the undulating roof surface are favourite spots for house sparrows to sun themselves. When the snows arrive the tiles are quickly covered. However, I always look forward to the thaw because pleasing patterns are made by the retreating snow. Squally March snow showers have afflicted us recently and today's photograph shows the roof after a spell of sunshine had begun to do its work.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 37.1mm (100mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5

Shutter Speed: 1/2000

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

The first flat clay tiles (plain tiles) in England were probably those introduced by the Romans. They manufactured them here too and examples can still be found in the cities, towns and villas that were built during their time in these islands. Medieval masons found them and incorporated some in their walling, though they increasingly manufactured their own plain tiles as a fire-proof replacement for thatch.The pantile with its "S" shaped curve was introduced into England from the Low Countries in the seventeenth century. Its name derives from the old Dutch "dakpan" (roof pan) and the German "pfannenziegel" (pantile). They quickly became popular in the eastern counties of our country where thatch predominated and roofing stone was scarce. In these areas, by the eighteenth century, pantiles were the roof covering of choice for anyone with a reasonable amount of money. Today they are still manufactured, still used for roofs and there are still examples from the earliest times to be seen on roofs, continuing to protect the buildings that often date from centuries ago.

Twentieth century manufacturers of concrete tiles weren't slow to realise the beauty of pantiles and the ease with which they are laid, overlapping each other and hooked over wooden battens. My garage, a modern structure, is roofed with a variant of this design and the tiles have weathered to a quite pleasing dark, mottled hue that in every aspect, except south-facing, grows a patina of moss and lichen. In spring and summer the low parts of the undulating roof surface are favourite spots for house sparrows to sun themselves. When the snows arrive the tiles are quickly covered. However, I always look forward to the thaw because pleasing patterns are made by the retreating snow. Squally March snow showers have afflicted us recently and today's photograph shows the roof after a spell of sunshine had begun to do its work.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 37.1mm (100mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5

Shutter Speed: 1/2000

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Sunday, March 10, 2013

Working with animals and children

click photo to enlarge

I've never been tempted by the lure of stage or screen, the bright lights, the red carpet or the adulation of fans. Just as well really because I'd be useless at it all.

In fact the only time I've ever appeared in the media - press, radio or TV (web too I suppose apart from links with photography and architecture) is in connection with a relatively minor news story. That happened to me last week when I did a regional TV interview and was once again reminded of the tedium of doing several "takes" to get a few seconds of footage. I've done that sort of thing before in connection with my job and when campaigning, but not for a few years. Last week reminded me of the unreality of what passes for real.

One of the sayings that actors are known for is, "never work with children or animals". It's a quote that's often attributed to W.C. Fields and it sounds like the sort of thing he would say. I was reminded of it this afternoon when I was photographing a horse. I'd been chatting with a couple of friends and prevailed on them to let me take a few shots of one of their horses because my stock of shots for the blog was running low. Why did the quote come to mind? Well, the horse in question was even less co-operative as a photographic subject than my grand-daughter. It would not stay still, and when it remained in one place it moved its head about. I made a good collection of blurred shots. Very much as I often do with my grand-daughter in fact! However, eventually I got a couple that looked like they might work. I took the opportunity to further test the Aperture Priority mode of the RX100 and took this shot in the dark of the stable. It did a fair job. I'd dialled in some negative EV to give a little "mood" to the shot and for this image I've done some "burning" of the edges to give something of a vignette.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 18.5mm (50mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5

Shutter Speed: 1/60

ISO: 2000

Exposure Compensation: -1.0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

I've never been tempted by the lure of stage or screen, the bright lights, the red carpet or the adulation of fans. Just as well really because I'd be useless at it all.

In fact the only time I've ever appeared in the media - press, radio or TV (web too I suppose apart from links with photography and architecture) is in connection with a relatively minor news story. That happened to me last week when I did a regional TV interview and was once again reminded of the tedium of doing several "takes" to get a few seconds of footage. I've done that sort of thing before in connection with my job and when campaigning, but not for a few years. Last week reminded me of the unreality of what passes for real.

One of the sayings that actors are known for is, "never work with children or animals". It's a quote that's often attributed to W.C. Fields and it sounds like the sort of thing he would say. I was reminded of it this afternoon when I was photographing a horse. I'd been chatting with a couple of friends and prevailed on them to let me take a few shots of one of their horses because my stock of shots for the blog was running low. Why did the quote come to mind? Well, the horse in question was even less co-operative as a photographic subject than my grand-daughter. It would not stay still, and when it remained in one place it moved its head about. I made a good collection of blurred shots. Very much as I often do with my grand-daughter in fact! However, eventually I got a couple that looked like they might work. I took the opportunity to further test the Aperture Priority mode of the RX100 and took this shot in the dark of the stable. It did a fair job. I'd dialled in some negative EV to give a little "mood" to the shot and for this image I've done some "burning" of the edges to give something of a vignette.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 18.5mm (50mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5

Shutter Speed: 1/60

ISO: 2000

Exposure Compensation: -1.0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, March 08, 2013

Testing 1, 2

click photo to enlarge

Television in the UK seems so much less adventurous than it was in the 1960s and 1970s or even the 1980s. Despite hundreds of channels operating 24 hours a day I often find there is nothing that I want to watch. Maybe it's me. But perhaps it isn't. Where, today, is the commissioning editor who would fund not just one series but multiple series' by the likes of Neil Innes or Alexei Sayle? Who would recognise the acute observation and quirky brilliance of Innes' musical offerings, or Alexei's in-your-face barrage of invective that pricked the inflated self-regard of the English middle classes, and then go on to persuade a channel that it would soon find a relatively small, but very partisan and dedicated audience?

So dire is today's television that sometimes I use YouTube as my source of entertainment, and often find myself listening to Neil Innes wonderful musical parodies or Alexei Sayle's assault on politics or the vagaries of modern life. I was doing so the other day when I stumbled once more on a throw-away piece by Neil Innes, less than a minute long, but one that is so well-observed, re-creating as it does the kind of semi-professional band that used to be found touring English working men's clubs or performing at weddings. It's not laugh out loud stuff like "Protest Song", "Godfrey Daniel" or "Crystal Balls", but it always raises a smile on my face.

And the connection with today's photograph of a churchyard at twenty two minutes past seven on a recent dark and slightly wet evening is...? Well, that piece of music is called "Testing 1, 2", and in taking my photograph in such unpromising circumstances I was doing something I hardly ever do: I was testing a feature on the Sony RX100. The only testing of kit that I undertake involves looking at my photographs, drawing conclusions about the success or otherwise of the camera in those circumstances, and modifying (or not) my practice accordingly. Here I was trying out the Superior Intelligent Auto mode (what a name!) that, in dim or dark conditions takes several quick exposures after one press of the shutter button and then makes an amalgamated shot of those images that attempts to cancel out the noise. This noise cancelling technology has been available on some cameras for a few years, though on none I've owned. I do have software for a dedicated film and negative scanner that makes 2,4,8 or 16 passes to achieve the same thing and that works very well. The result of my test is that the Sony mode is pretty effective too and much, MUCH quicker.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: iAuto+

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f1.8

Shutter Speed: 1/4

ISO: 3200

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Television in the UK seems so much less adventurous than it was in the 1960s and 1970s or even the 1980s. Despite hundreds of channels operating 24 hours a day I often find there is nothing that I want to watch. Maybe it's me. But perhaps it isn't. Where, today, is the commissioning editor who would fund not just one series but multiple series' by the likes of Neil Innes or Alexei Sayle? Who would recognise the acute observation and quirky brilliance of Innes' musical offerings, or Alexei's in-your-face barrage of invective that pricked the inflated self-regard of the English middle classes, and then go on to persuade a channel that it would soon find a relatively small, but very partisan and dedicated audience?

So dire is today's television that sometimes I use YouTube as my source of entertainment, and often find myself listening to Neil Innes wonderful musical parodies or Alexei Sayle's assault on politics or the vagaries of modern life. I was doing so the other day when I stumbled once more on a throw-away piece by Neil Innes, less than a minute long, but one that is so well-observed, re-creating as it does the kind of semi-professional band that used to be found touring English working men's clubs or performing at weddings. It's not laugh out loud stuff like "Protest Song", "Godfrey Daniel" or "Crystal Balls", but it always raises a smile on my face.

And the connection with today's photograph of a churchyard at twenty two minutes past seven on a recent dark and slightly wet evening is...? Well, that piece of music is called "Testing 1, 2", and in taking my photograph in such unpromising circumstances I was doing something I hardly ever do: I was testing a feature on the Sony RX100. The only testing of kit that I undertake involves looking at my photographs, drawing conclusions about the success or otherwise of the camera in those circumstances, and modifying (or not) my practice accordingly. Here I was trying out the Superior Intelligent Auto mode (what a name!) that, in dim or dark conditions takes several quick exposures after one press of the shutter button and then makes an amalgamated shot of those images that attempts to cancel out the noise. This noise cancelling technology has been available on some cameras for a few years, though on none I've owned. I do have software for a dedicated film and negative scanner that makes 2,4,8 or 16 passes to achieve the same thing and that works very well. The result of my test is that the Sony mode is pretty effective too and much, MUCH quicker.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: iAuto+

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f1.8

Shutter Speed: 1/4

ISO: 3200

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, March 06, 2013

Deserted streets and old photographs

click photo to enlarge

One of the characteristics of old photographs of country towns and villages is the relative absence of people and vehicles. In particular, the motor cars that are everywhere today are noticeable by their absence. Old photographs of that sort give us a feel for what we have surrendered to the motor vehicle's relentless growth and spread. Of course not all old photographs have this characteristic. City shots taken in the second half of the Victorian period frequently teem with life - people, horses, carriages and carts, sometimes livestock on its way to market or slaughter. But in the smaller settlements a typical shot has no one, or perhaps just a few people, often standing still, gazing with interest at the camera as the photographer records that moment in time.

A few days ago I was in the small Lincolnshire town of Horncastle. As I walked along West Street, a main thoroughfare at the edge of the centre of the settlement, I gazed at the Victorian, Georgian and older buildings that line the way. As is the case in quite a few towns in this eastern county, they have not been "messed about with" too much, and still display much of the character that they adopted when first built. Looking at the scene I mentally took out the roof aerials, street lights and the tarmac road with its markings. As I was doing so an amazing thing happened. The vehicles that had been passing singly and in groups stopped appearing. For a minute or so West Street became deserted and I seemed to step back in time to about one hundred and fifty years ago. I took my shot of the empty road. When I came to process it on the computer I only needed to convert it to black and white to complete the illusion.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: iAuto

Focal Length: 28.8mm (78mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/250

ISO: 160

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Tuesday, March 05, 2013

Wrawby windmill

click photo to enlarge

The mill at Wrawby that stands proudly on the escarpment above the Ancholme valley is the sole survivor of the Lincolnshire post mills. There were once many windmills of this design, structures that were mounted on a single vertical pole and turned to face the wind by means of a projecting beam rather than the later fantail. Wrawby is a Midlands development of this basic post mill design with a roundhouse made of brick surrounding the supporting trestle and some of the weight of the upper structure borne by wheels and runners on the top of the brick wall. A windmill has been on this site since at least the sixteenth century though the building we see today was constructed in 1832 from the remains of an earlier open trestle mill. It worked until the second world war powered by wind, then steam and finally oil, and after its abandonment fell into serious disrepair.

By the 1960s the mill was close to total collapse: sails were missing, much of the weatherboarding had fallen off, and an application was made for its demolition. However, a stay of execution appeared in the form of a trust set up to preserve it. What followed has been described as "the most comprehensive rebuilding of a windmill undertaken in this country since the nineteenth century." Original components and newly fabricated timbers were assembled to restore the mill to how it had been. The work was completed by a mixture of enthusiasts, academics, former millers, and carpenters and culminated in its official opening on 18th September 1965.

Prior to the invention of spring regulated sails that allowed shutters to be positioned to catch the wind or let it pass through, many windmills used what were known as "common sails". These were cloth sails, edged canvas made of hemp, flax or cotton, fixed to the wooden structure of each sail. Like the sails on a sailing ship the area of canvas could be reefed in if the wind speed increased to a speed greater than was required for efficient milling. An old photo shows this type of canvas sail fixed to the wooden sails of Wrawby mill.

The weather on the afternoon of my visit - hazy sun trying to burn its way through cloud that had made the morning quite dark - gave enough shadow to model the structure but left the bluish sky looking rather weak and washed out. Consequently I converted my photographs to black and white and applied a digital orange filter to increase the contrast.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 20mm (54mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/800

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

The mill at Wrawby that stands proudly on the escarpment above the Ancholme valley is the sole survivor of the Lincolnshire post mills. There were once many windmills of this design, structures that were mounted on a single vertical pole and turned to face the wind by means of a projecting beam rather than the later fantail. Wrawby is a Midlands development of this basic post mill design with a roundhouse made of brick surrounding the supporting trestle and some of the weight of the upper structure borne by wheels and runners on the top of the brick wall. A windmill has been on this site since at least the sixteenth century though the building we see today was constructed in 1832 from the remains of an earlier open trestle mill. It worked until the second world war powered by wind, then steam and finally oil, and after its abandonment fell into serious disrepair.

By the 1960s the mill was close to total collapse: sails were missing, much of the weatherboarding had fallen off, and an application was made for its demolition. However, a stay of execution appeared in the form of a trust set up to preserve it. What followed has been described as "the most comprehensive rebuilding of a windmill undertaken in this country since the nineteenth century." Original components and newly fabricated timbers were assembled to restore the mill to how it had been. The work was completed by a mixture of enthusiasts, academics, former millers, and carpenters and culminated in its official opening on 18th September 1965.

Prior to the invention of spring regulated sails that allowed shutters to be positioned to catch the wind or let it pass through, many windmills used what were known as "common sails". These were cloth sails, edged canvas made of hemp, flax or cotton, fixed to the wooden structure of each sail. Like the sails on a sailing ship the area of canvas could be reefed in if the wind speed increased to a speed greater than was required for efficient milling. An old photo shows this type of canvas sail fixed to the wooden sails of Wrawby mill.

The weather on the afternoon of my visit - hazy sun trying to burn its way through cloud that had made the morning quite dark - gave enough shadow to model the structure but left the bluish sky looking rather weak and washed out. Consequently I converted my photographs to black and white and applied a digital orange filter to increase the contrast.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 20mm (54mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/800

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Sunday, March 03, 2013

Hebe, ambrosia and shrubs

click photo to enlarge

As far as I can see Greek mythology doesn't figure much in the education or interests of school children today. Yet when I was a child we were taught quite a bit about the subject, including some of the best known stories, and this made us (well, certainly me) want to know more. Alexander Pope said that "a little learning is a dangerous thing", and it certainly can be. However, in the case of me and Greek mythology it proved to be one of the catalysts that inspired a love of words and their origins.

It all started with "Ambrosia" creamed rice, a tinned rice pudding from Devon that first came on the market just before the second world war and was a family staple in the 1950s and 1960s. I discovered that the Greek gods fed on ambrosia and that Zeus and Hera received it (with nectar) from their daughter. It didn't take much research to discover that their ambrosia was unlikely to be the kind with which I was familiar, but the derivation of the rice pudding's name was something I found very interesting.

What has all this to do with a shallow depth of field photograph of a sprig of the plant, Hebe "Red Edge", I hear you ask. Well, the name of the daughter of Zeus and Hera was Hebe. She was the goddess of youth and cup-bearer to the gods until she married Heracles (Hercules to the Romans). When, later in life, I again came across the name Hebe it wasn't in connection with mythology but rather as a very useful, usually hardy, evergreen shrub that originated in New Zealand and South America, one that usually did well in the sort of coastal environment where I was living at the time. It's a plant I've always liked, and a variety that I particularly appreciate is the one shown in today's photograph. The blue-green of the leaf sits well with the red-purple of the leaf edges and makes it an attractive plant all year round. I was photographing our wych hazel when the very structured branches of opposing leaves caught my eye. I composed this shot to hint at the structure and clearly reveal the tip. Incidentally, I have no idea why this particular name was applied to this genus of plant!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 100mm macro

F No: f4

Shutter Speed: 1/100 sec

ISO: 200 Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

As far as I can see Greek mythology doesn't figure much in the education or interests of school children today. Yet when I was a child we were taught quite a bit about the subject, including some of the best known stories, and this made us (well, certainly me) want to know more. Alexander Pope said that "a little learning is a dangerous thing", and it certainly can be. However, in the case of me and Greek mythology it proved to be one of the catalysts that inspired a love of words and their origins.

It all started with "Ambrosia" creamed rice, a tinned rice pudding from Devon that first came on the market just before the second world war and was a family staple in the 1950s and 1960s. I discovered that the Greek gods fed on ambrosia and that Zeus and Hera received it (with nectar) from their daughter. It didn't take much research to discover that their ambrosia was unlikely to be the kind with which I was familiar, but the derivation of the rice pudding's name was something I found very interesting.

What has all this to do with a shallow depth of field photograph of a sprig of the plant, Hebe "Red Edge", I hear you ask. Well, the name of the daughter of Zeus and Hera was Hebe. She was the goddess of youth and cup-bearer to the gods until she married Heracles (Hercules to the Romans). When, later in life, I again came across the name Hebe it wasn't in connection with mythology but rather as a very useful, usually hardy, evergreen shrub that originated in New Zealand and South America, one that usually did well in the sort of coastal environment where I was living at the time. It's a plant I've always liked, and a variety that I particularly appreciate is the one shown in today's photograph. The blue-green of the leaf sits well with the red-purple of the leaf edges and makes it an attractive plant all year round. I was photographing our wych hazel when the very structured branches of opposing leaves caught my eye. I composed this shot to hint at the structure and clearly reveal the tip. Incidentally, I have no idea why this particular name was applied to this genus of plant!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 100mm macro

F No: f4

Shutter Speed: 1/100 sec

ISO: 200 Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, March 01, 2013

Out with the LX3, in with the RX100

Perhaps I was tempting fate posting a piece entitled "In praise of things compact" because shortly after I'd done so my LX3 compact camera began, first to play up and then to enter a process of serious decline. Whether the fault is mechanical or electrical I don't know, but the symptoms involve me pressing the shutter, the camera appearing to go through the appropriate motions, and nothing being recorded. Or the display doesn't work. Or an error message appears asking me to re-insert the memory card. I tried a different card and cleaned the battery terminals and card connectors but to no avail. At the point where the camera was sometimes working but usually failing to do so I decided enough was enough and bought a Sony RX100.

I like to use a compact camera, and despite having an initial aversion to those cameras that didn't have viewfinders I've grown to like composing on a large screen. The Sony's is supposed to be fairly acceptable in bright summer sunshine. We shall see! The RX100 will become my "carry everywhere when I'm not carrying the DSLR" camera. It is eminently suited to that role being slightly smaller and lighter than the LX3. It will also be the camera of choice when I'm photographing in the street because it is much less intrusive and intimidating than a big DSLR.

I like to use a compact camera, and despite having an initial aversion to those cameras that didn't have viewfinders I've grown to like composing on a large screen. The Sony's is supposed to be fairly acceptable in bright summer sunshine. We shall see! The RX100 will become my "carry everywhere when I'm not carrying the DSLR" camera. It is eminently suited to that role being slightly smaller and lighter than the LX3. It will also be the camera of choice when I'm photographing in the street because it is much less intrusive and intimidating than a big DSLR.So far I'm very pleased with the RX100. I'm especially enjoying the two axis electronic level - great for architecture and it reduces post processing time. I also like the facility to take a single shot that combines three versions to reduce noise and improve quality: that's very useful inside poorly lit churches. Most of all, I've been impressed by the quality of jpeg and RAW images: that one inch sensor does better than I imagined it would. Not for nothing is it only one of two fixed lens compact cameras that Alamy has on its recommended camera list (the other being the Leica X1). I gave the camera a workout recently, testing its iAuto modes, and as part of it I visited the medieval church of St Mary at Pinchbeck. Here are two of the shots I took that I've converted to black and white.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Sony RX100

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 10.4mm (28mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/400

ISO: 125

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

.jpg)