click photo to enlarge

Anyone familiar with the Modernist work of R.Mutt aka Marcel Duchamp and the Belgian Surrealist, René Magritte, will understand the allusion in today's blog post title. It was the combination of the former's "fountain", that is to say a porcelain urinal signed "R. Mutt", combined with the title of the latter's painting of a pipe, that came to mind when I walked into this red and white men's toilet in a Lincolnshire building.As my eyes took in the cool, pristine white shapes, the astonishing red, and the way they worked together, it became obvious this was intended to be a room that offered an aesthetic experience as well as one that efficiently catered for the bodily needs of its visitors.

As I reflected further it struck me that the sanitaryware manufacturer, Armitage Shanks, had designed the white porcelain urinals (the "Aridian" waterless model no less ) and the intervening modesty screens to be sculptural objects. Not quite art, but craft with pretensions to art, the sort of minimalist work that would complement an avowedly modern building (of the sort in which these were located). One could almost see a collection of these on a black plinth lit by highly directional spotlights in a London gallery. The architect must have had thoughts along these lines because he (or she) had clearly chosen the grid of blood-red wall panels, cubicle dividers and doors to accentuate the stylish shapes. No, I thought, reflecting one more on Duchamp, these were definitely not just utilitarian, bog standard (pun intended) objects; they aspired to be something greater.

By the way, I apologise to any French speaking readers, or anyone who speaks French better than I do - that's most people - if my title mangles the language. It's a combination of my rudimentary skill and Google Translate.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 28mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/30

ISO: 3200

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Pages

▼

Sunday, December 30, 2012

Saturday, December 29, 2012

Not so new year

click photo to enlarge

Many pages of today's newspapers look like they were written a while ago and took as their template the newspapers of last year, the year before, the year before that, etc. So we have the all too predictable reviews of the sporting year, highlights of the political year, coverage of the year in entertainment, gadget of the year, camera of the year and so on, accompanied by the inevitable quiz of the year. It must be drudgery of the first order to write these pages, and it's not much better having to read them. In fact, I don't, and I haven't for many years.

Unfortunately, in Britain this recycled news is in the newspapers at the same time that the New Year Honours List is published - the gongs and titles given to the great, the good, the not so good, the toadies, backslappers and political party paymasters of the land. The first I read of this year's installment of the annual absurdity was a while ago when it became public knowledge that Danny Boyle, the film director and the person behind the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games had refused the knighthood that had been offered to him. Good for you I thought. Not only was it the right decision, he'd put himself in good company. But, when I glanced at today's list of those who had played along with this anachronistic nonsense, my heart sank. However, the mood of despondency was short-lived because I then read Tanya Gould's article in today's Guardian newspaper - "New year honours are little more than postcard pomp", and was pleased to find someone who shared my views and was able to articulate the absurdity of this yearly ritual. I strongly recommend it.

All this, of course, has nothing to do with today's photograph of window cleaners at work on the side of one of London's many glass-walled office buildings.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 105mm

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/125

ISO: 1600

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Many pages of today's newspapers look like they were written a while ago and took as their template the newspapers of last year, the year before, the year before that, etc. So we have the all too predictable reviews of the sporting year, highlights of the political year, coverage of the year in entertainment, gadget of the year, camera of the year and so on, accompanied by the inevitable quiz of the year. It must be drudgery of the first order to write these pages, and it's not much better having to read them. In fact, I don't, and I haven't for many years.

Unfortunately, in Britain this recycled news is in the newspapers at the same time that the New Year Honours List is published - the gongs and titles given to the great, the good, the not so good, the toadies, backslappers and political party paymasters of the land. The first I read of this year's installment of the annual absurdity was a while ago when it became public knowledge that Danny Boyle, the film director and the person behind the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games had refused the knighthood that had been offered to him. Good for you I thought. Not only was it the right decision, he'd put himself in good company. But, when I glanced at today's list of those who had played along with this anachronistic nonsense, my heart sank. However, the mood of despondency was short-lived because I then read Tanya Gould's article in today's Guardian newspaper - "New year honours are little more than postcard pomp", and was pleased to find someone who shared my views and was able to articulate the absurdity of this yearly ritual. I strongly recommend it.

All this, of course, has nothing to do with today's photograph of window cleaners at work on the side of one of London's many glass-walled office buildings.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 105mm

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/125

ISO: 1600

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Thursday, December 27, 2012

Signs and sentience

click photo to enlarge

Over the years I've posted quite a few photographs of signs. Some of them, such as the recent one of the London Underground roundel show specimens displaying exemplary design, others, as is the case with this old road sign, illustrate how signs in the past emphasised the message much more than presentation. However, it is those signs that say more than the writer intended that I enjoy most of all.

I particularly relished the sign I came across in Williamson Park, Lancaster, that proclaimed, "Danger - Shallow Water" and I had to drive carefully and look behind every tree and bush when I came upon the sign at Bleasdale, Lancashire, that said, "Slow - Children & Dogs Everywhere". Then there was the sign on a Blackpool pier exhorting visitors not to attach bicycles to the railings because to do so was a fire hazard. I felt I had little choice but to give that blog post the title, "Incendiary bicycles?"

When I decided that my garden shed needed its security improving I took a few basic measures to make it more difficult for a burglar to enter. I also cast around for a sign that would increase the deterrent effect. When I saw this one I simply had to buy it. I loved the idea that my shed is sentient and has feelings just like you and me, though every time I see it I do wonder what I could have done to cause it such consternation.

Incidentally, this image shows a photographic optical illusion of a kind that I've noticed before. The writing on the sign is engraved, yet sometimes it appears to be embossed depending on how you visually interpret the shadows in the indentations. Another example of the phenomenon can be seen in this old graffiti on the medieval stonework of the tower of St Botolph in Boston, Lincolnshire

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 100mm macro

F No: f11

Shutter Speed: 100 sec

ISO: 160

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Over the years I've posted quite a few photographs of signs. Some of them, such as the recent one of the London Underground roundel show specimens displaying exemplary design, others, as is the case with this old road sign, illustrate how signs in the past emphasised the message much more than presentation. However, it is those signs that say more than the writer intended that I enjoy most of all.

I particularly relished the sign I came across in Williamson Park, Lancaster, that proclaimed, "Danger - Shallow Water" and I had to drive carefully and look behind every tree and bush when I came upon the sign at Bleasdale, Lancashire, that said, "Slow - Children & Dogs Everywhere". Then there was the sign on a Blackpool pier exhorting visitors not to attach bicycles to the railings because to do so was a fire hazard. I felt I had little choice but to give that blog post the title, "Incendiary bicycles?"

When I decided that my garden shed needed its security improving I took a few basic measures to make it more difficult for a burglar to enter. I also cast around for a sign that would increase the deterrent effect. When I saw this one I simply had to buy it. I loved the idea that my shed is sentient and has feelings just like you and me, though every time I see it I do wonder what I could have done to cause it such consternation.

Incidentally, this image shows a photographic optical illusion of a kind that I've noticed before. The writing on the sign is engraved, yet sometimes it appears to be embossed depending on how you visually interpret the shadows in the indentations. Another example of the phenomenon can be seen in this old graffiti on the medieval stonework of the tower of St Botolph in Boston, Lincolnshire

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 100mm macro

F No: f11

Shutter Speed: 100 sec

ISO: 160

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, December 26, 2012

Photographic decisions

click photo to enlarge

Every time we take a photograph we make decisions. If we assume that we've already decided the nature of the subject then the first one concerns what part of our field of view we will use as the composition or whether we will we use it all. Having decided that we have to consider what we want to say through the photograph - what it's about. Is it representational reportage where the subject is all important and we are saying, "look at this", to the viewer? Is the way we show the subject, the viewpoint we adopt, the way we use light, composition, colour etc. important, so that the image us as much about the photographers vision as it is the subject, and we are inviting the viewer to look at the subject in our particular way? Or is there an intention to introduce an element of abstraction, to make the viewer wonder what they are looking at and why the image was conceived in that way? There are other decisions to be made, of course, but these three interest me because I deliberately exploit them all at various times in my photography.

Today's photograph falls into the last of these three categories. I took it one evening in London as I looked up at the darkening sky with its pink-tinged clouds and their reflection on the glass of the office buildings. I wanted to make a photograph with very little in it, that concentrated on just a few elements arranged in a simple composition. Moreover, I was keen to produce an image where the component parts would be appreciated for their intrinsic graphic qualities rather than because they were part of the recognisable, real world. The shot I came up with is divided into two halves by a diagonal line, sky and clouds on one side, glass, glazing bars and cladding on the other. It contrasts softness and irregularity with hardness and regular linearity, the colours o the sky and their reflections uniting the two halves, with an element of abstraction to complete the mix.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: LX3

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 12.8mm (60mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: 2.8

Shutter Speed: 1/125

ISO: 400

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Every time we take a photograph we make decisions. If we assume that we've already decided the nature of the subject then the first one concerns what part of our field of view we will use as the composition or whether we will we use it all. Having decided that we have to consider what we want to say through the photograph - what it's about. Is it representational reportage where the subject is all important and we are saying, "look at this", to the viewer? Is the way we show the subject, the viewpoint we adopt, the way we use light, composition, colour etc. important, so that the image us as much about the photographers vision as it is the subject, and we are inviting the viewer to look at the subject in our particular way? Or is there an intention to introduce an element of abstraction, to make the viewer wonder what they are looking at and why the image was conceived in that way? There are other decisions to be made, of course, but these three interest me because I deliberately exploit them all at various times in my photography.

Today's photograph falls into the last of these three categories. I took it one evening in London as I looked up at the darkening sky with its pink-tinged clouds and their reflection on the glass of the office buildings. I wanted to make a photograph with very little in it, that concentrated on just a few elements arranged in a simple composition. Moreover, I was keen to produce an image where the component parts would be appreciated for their intrinsic graphic qualities rather than because they were part of the recognisable, real world. The shot I came up with is divided into two halves by a diagonal line, sky and clouds on one side, glass, glazing bars and cladding on the other. It contrasts softness and irregularity with hardness and regular linearity, the colours o the sky and their reflections uniting the two halves, with an element of abstraction to complete the mix.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: LX3

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 12.8mm (60mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: 2.8

Shutter Speed: 1/125

ISO: 400

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Monday, December 24, 2012

And so this is Christmas

click photo to enlarge

Christmas has crept up on me this year. I noticed it coming on a few occasions, but deliberately put it out of my mind except when making and writing a few cards, buying some presents and doing the shopping. Then, suddenly, out of almost nowhere, it's Christmas Eve. My wife has done many of the necessaries required to make Christmas as it should be, and for that I am, once again, grateful. How she puts up living with Scrooge, I don't know!

The appeal of Christmas has declined for me over the years. It's the conspicuous consumption that it entails and the interruptions to my routine that it presents, but mostly because it rarely compares to the Christmases that I so enjoyed when our children were young. Perhaps - and I've just thought of this - Christmas makes me feel my age. Last year I quite enjoyed it and next year, well, who knows? Of course, I'm not alone in my ambivalence towards the festive season. Charles Dickens, whose books both celebrated and helped to define the modern Christmas also had this to say about it (through his character, Scrooge): "Every idiot who goes about with 'Merry Christmas' on his lips should be boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart." If that sounds a touch too misanthropic (and I have to say I wouldn't endorse it!) let me make it even more so with Gore Vidal's Christmas greeting: "Meretricious and a Happy New Year", and Samuel Butler's prayer: "Forgive us our Christmases as we forgive those that Christmas against us."

Today's main photograph is the only shot I have from this year that has any connection with the festive season. The two Christmas trees with lights standing on the front of Inigo Jones' superlative building of 1616-19, Queen's House in Greenwich Park, London, are my excuse for posting this image today. However, when I think about it, this post could also be an example to support the thesis of my blog post of earlier this year, "Look behind you", because the shot of Christopher Wren's Old Royal Naval College (formerly the Royal Hospital for Seamen) of 1696-1712, were taken from precisely the same spot as the Queen's House photograph, but looking in the opposite direction

After the downbeat opening of this post perhaps a little uplift is required, so here, in conclusion, are four of my favourite Christmas jokes:

"I bought my kids a set of batteries for Christmas with a note attached saying, 'Toys not included'". Anon

"My mother in law has come round to our house at Christmas seven years running. This year we're having a change. We're going to let her in." Les Dawson

"Aren't we forgetting the true meaning of Christmas - the birth of Santa?" Bart Simpson

"It will be a traditional Christmas with presents, crackers, doors slamming and people bursting into tears, but without the dead thing in the middle. We're vegetarians." Victoria Wood

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 40mm

F No: f6.3

Shutter Speed: 1/13

ISO: 3200

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Christmas has crept up on me this year. I noticed it coming on a few occasions, but deliberately put it out of my mind except when making and writing a few cards, buying some presents and doing the shopping. Then, suddenly, out of almost nowhere, it's Christmas Eve. My wife has done many of the necessaries required to make Christmas as it should be, and for that I am, once again, grateful. How she puts up living with Scrooge, I don't know!

The appeal of Christmas has declined for me over the years. It's the conspicuous consumption that it entails and the interruptions to my routine that it presents, but mostly because it rarely compares to the Christmases that I so enjoyed when our children were young. Perhaps - and I've just thought of this - Christmas makes me feel my age. Last year I quite enjoyed it and next year, well, who knows? Of course, I'm not alone in my ambivalence towards the festive season. Charles Dickens, whose books both celebrated and helped to define the modern Christmas also had this to say about it (through his character, Scrooge): "Every idiot who goes about with 'Merry Christmas' on his lips should be boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart." If that sounds a touch too misanthropic (and I have to say I wouldn't endorse it!) let me make it even more so with Gore Vidal's Christmas greeting: "Meretricious and a Happy New Year", and Samuel Butler's prayer: "Forgive us our Christmases as we forgive those that Christmas against us."

Today's main photograph is the only shot I have from this year that has any connection with the festive season. The two Christmas trees with lights standing on the front of Inigo Jones' superlative building of 1616-19, Queen's House in Greenwich Park, London, are my excuse for posting this image today. However, when I think about it, this post could also be an example to support the thesis of my blog post of earlier this year, "Look behind you", because the shot of Christopher Wren's Old Royal Naval College (formerly the Royal Hospital for Seamen) of 1696-1712, were taken from precisely the same spot as the Queen's House photograph, but looking in the opposite direction

After the downbeat opening of this post perhaps a little uplift is required, so here, in conclusion, are four of my favourite Christmas jokes:

"I bought my kids a set of batteries for Christmas with a note attached saying, 'Toys not included'". Anon

"My mother in law has come round to our house at Christmas seven years running. This year we're having a change. We're going to let her in." Les Dawson

"Aren't we forgetting the true meaning of Christmas - the birth of Santa?" Bart Simpson

"It will be a traditional Christmas with presents, crackers, doors slamming and people bursting into tears, but without the dead thing in the middle. We're vegetarians." Victoria Wood

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 40mm

F No: f6.3

Shutter Speed: 1/13

ISO: 3200

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Thursday, December 20, 2012

War Memorial, Boston

click photo to enlarge

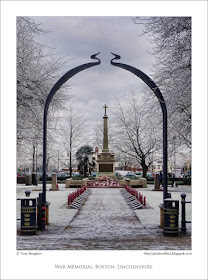

It's always gratifying to see the respect that is widely given to war memorials. But it isn't everyone who gives them, or what they represent, the recognition that they deserve. I read recently about the prosecution of some despicable people who had forced the brass plaques recording the dead of two world wars off a memorial and sold them to a scrap metal dealer! Thankfully such low-life are very much the exception and most people know that our remembrance of those who fought on our behalf is important and should be accorded respect.

Today's photograph shows the war memorial and its enclosing garden of remembrance in Wide Bargate, Boston, in Lincolnshire. It is fairly typical of a town war memorial with its stone column, a base recording the dead of the town, and a surrounding area to receive the tributes of subsequent generations. What does make it slightly different, however, are the two rows of small, inclined and engraved marble tablets seen on either side of the path leading to the memorial. Each of these shows the name and insignia of an arm of the military, a regiment or an associated organisation. It is a place for representatives of these bodies to place a wreath on Remembrance Day. The wreaths of civic bodies and others are at the base of the memorial. I took my photograph in late December of last year, five or six weeks after the poppy wreaths had been laid, and they were still where they had been placed, undisturbed by weather or any person. One other thing that distinguishes the Boston war memorial site is the steel entrance arch. This graceful construction that terminates with Art Nouveau-like flourishes is sometimes a little lost against the background trees, leaves and buildings. However, on this frosty morning with a thin layer of snow covering everything, it stood out, clear and elegant, a perfect frame for my shot.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Lumix LX3

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 12.8mm (60mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f3.5

Shutter Speed: 1/500

ISO:80

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

It's always gratifying to see the respect that is widely given to war memorials. But it isn't everyone who gives them, or what they represent, the recognition that they deserve. I read recently about the prosecution of some despicable people who had forced the brass plaques recording the dead of two world wars off a memorial and sold them to a scrap metal dealer! Thankfully such low-life are very much the exception and most people know that our remembrance of those who fought on our behalf is important and should be accorded respect.

Today's photograph shows the war memorial and its enclosing garden of remembrance in Wide Bargate, Boston, in Lincolnshire. It is fairly typical of a town war memorial with its stone column, a base recording the dead of the town, and a surrounding area to receive the tributes of subsequent generations. What does make it slightly different, however, are the two rows of small, inclined and engraved marble tablets seen on either side of the path leading to the memorial. Each of these shows the name and insignia of an arm of the military, a regiment or an associated organisation. It is a place for representatives of these bodies to place a wreath on Remembrance Day. The wreaths of civic bodies and others are at the base of the memorial. I took my photograph in late December of last year, five or six weeks after the poppy wreaths had been laid, and they were still where they had been placed, undisturbed by weather or any person. One other thing that distinguishes the Boston war memorial site is the steel entrance arch. This graceful construction that terminates with Art Nouveau-like flourishes is sometimes a little lost against the background trees, leaves and buildings. However, on this frosty morning with a thin layer of snow covering everything, it stood out, clear and elegant, a perfect frame for my shot.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Lumix LX3

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 12.8mm (60mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f3.5

Shutter Speed: 1/500

ISO:80

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

The London Underground roundel

click photo to enlarge

There is a great temptation for companies to update their company name and logo to better reflect the times. If you look at companies as disparate as Shell, BP, Coca Cola, British Airways, Lego or Ford you can see a clear difference between the original logo and that of today, often with intervening versions along the way.

Companies that stick to their original logo or way of presenting their company name are fewer. Why is this? Could it be that they don't want, in some way, to dilute or muddy their brand by departing from what is tried, tested and successful? Or is it that they think they have found a design upon which improvement is impossible? BMW is an example of a company whose logo has changed little since its inception around 1920. The linked letter Cs of Chanel have also remained the same since the design was conceived by Coco Chanel in 1925.

A further example of a long-lasting logo is that of London Underground. The red roundel with a blue bar across upon which are the white letters - either "UNDERGROUND" or a station name - dates from 1908. There is the suggestion that it was adapted from the wheel with a bar across it used by the London General Omnibus Company in the nineteenth century. However, what is known is that a slight variation of the present design with the word "Underground" presented thus - UNDERGROUND - was first used in 1908 and that in 1919 Edward Johnston designed a sans serif typeface with all letters the same height for use throughout the London Underground, including on the roundel. It has remained the same since that time. The Transport for London (TfL) subsidiary, London Overground, adapted the roundel for its use, as did , London Buses (also a TfL subsidiary). All three logos can be seen on this sign near the determinedly modern Canada Water Library in London.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 28mm

F No: f6.3

Shutter Speed: 1/320

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

There is a great temptation for companies to update their company name and logo to better reflect the times. If you look at companies as disparate as Shell, BP, Coca Cola, British Airways, Lego or Ford you can see a clear difference between the original logo and that of today, often with intervening versions along the way.

Companies that stick to their original logo or way of presenting their company name are fewer. Why is this? Could it be that they don't want, in some way, to dilute or muddy their brand by departing from what is tried, tested and successful? Or is it that they think they have found a design upon which improvement is impossible? BMW is an example of a company whose logo has changed little since its inception around 1920. The linked letter Cs of Chanel have also remained the same since the design was conceived by Coco Chanel in 1925.

A further example of a long-lasting logo is that of London Underground. The red roundel with a blue bar across upon which are the white letters - either "UNDERGROUND" or a station name - dates from 1908. There is the suggestion that it was adapted from the wheel with a bar across it used by the London General Omnibus Company in the nineteenth century. However, what is known is that a slight variation of the present design with the word "Underground" presented thus - UNDERGROUND - was first used in 1908 and that in 1919 Edward Johnston designed a sans serif typeface with all letters the same height for use throughout the London Underground, including on the roundel. It has remained the same since that time. The Transport for London (TfL) subsidiary, London Overground, adapted the roundel for its use, as did , London Buses (also a TfL subsidiary). All three logos can be seen on this sign near the determinedly modern Canada Water Library in London.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 28mm

F No: f6.3

Shutter Speed: 1/320

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Monday, December 17, 2012

London and the Walkie Talkie

click photo to enlarge

A new building is appearing in the City of London at 20 Fenchurch Street and already the most eye-catching feature of its design is apparent. This 525 feet (160m) tall tower by the architect, Rafael Viñoly, flares outwards as it rises upwards, an unusual characteristic that has already earned it the nickname, the "Walkie Talkie". You can see it under construction on the left of my main photograph and on the right of the smaller one. This photograph gives an idea of what it will look like when it is completed in April 2014.

I've been fairly supportive of many of the new towers that have appeared in the City of London over the past twenty years or so. However, this building is one that I dislike for its shape and for the way it will intrude upon and overwhelm a location that has many fine and important buildings, including Tower Bridge. The developers must be aware of the disapprobation that the building has engendered because they plan to incorporate a three-level "sky garden" at the top with free access for the public. That has the potential to be visually interesting and very popular, but will do little to mitigate the intrusion of the massive building that will not only tower over its surroundings but will lean and loom over them too.

In some respects the idea of designing a building that offers more space than its footprint would usually allow is a clever and understandable one in an area where the price per square foot of property is so high. But it's not a new idea. The timber-framed "jettied" buildings of the Tudor period sought the same advantage. Moreover, though they didn't go anywhere near as high as the "Walkie Talkie" they did create dark, narrow streets and a sense of enclosure. This is already evident in parts of the City where tall, vertical buildings are adjacent to each other. It would only get worse if the idea encapsulated in this new building became a trend.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 183mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/250

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.00 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

A new building is appearing in the City of London at 20 Fenchurch Street and already the most eye-catching feature of its design is apparent. This 525 feet (160m) tall tower by the architect, Rafael Viñoly, flares outwards as it rises upwards, an unusual characteristic that has already earned it the nickname, the "Walkie Talkie". You can see it under construction on the left of my main photograph and on the right of the smaller one. This photograph gives an idea of what it will look like when it is completed in April 2014.

I've been fairly supportive of many of the new towers that have appeared in the City of London over the past twenty years or so. However, this building is one that I dislike for its shape and for the way it will intrude upon and overwhelm a location that has many fine and important buildings, including Tower Bridge. The developers must be aware of the disapprobation that the building has engendered because they plan to incorporate a three-level "sky garden" at the top with free access for the public. That has the potential to be visually interesting and very popular, but will do little to mitigate the intrusion of the massive building that will not only tower over its surroundings but will lean and loom over them too.

In some respects the idea of designing a building that offers more space than its footprint would usually allow is a clever and understandable one in an area where the price per square foot of property is so high. But it's not a new idea. The timber-framed "jettied" buildings of the Tudor period sought the same advantage. Moreover, though they didn't go anywhere near as high as the "Walkie Talkie" they did create dark, narrow streets and a sense of enclosure. This is already evident in parts of the City where tall, vertical buildings are adjacent to each other. It would only get worse if the idea encapsulated in this new building became a trend.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 183mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/250

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.00 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Sunday, December 16, 2012

Setts and cobblestones

click photo to enlarge

Many people assume that an old road that is laid with stones is "cobbled" and that such stones are called "cobblestones". The word "setts" isn't widely known, but where it is, there is a general belief that it is synonymous with cobbles. However, the two types of stone road surface are different.

The essence of the distinction is as follows: cobblestones are found and setts are made. So, cobblestones may be - and often are - large (bigger than 2.5 inches but smaller than 10 inches), water-worn pebbles, that are laid closely together, frequently irregularly, but sometimes with patterns and borders. Setts are cut, rectangular, blocks of stone, usually granite, that are laid in stepped parallel courses, rather like a horizontal, stretcher bond, wall. An example of a road constructed of granite setts is shown in today's photograph which shows Pilot Street in King's Lynn, Norfolk. Such a road is very durable, looks great, with the slight differences in colour of the setts adding to its appeal, but is somewhat uncomfortable to walk, cycle and drive over. It is for the latter reason that many British cobbled roads and those laid with setts were taken up or covered with a smooth layer of tarmacadam. However, many survived, and quite a few of those that were buried have since been revealed and repaired.

This particular street in King's Lynn has a charming and interesting collection of houses spanning several centuries and on one side borders the churchyard of the town's second largest medieval church, St Nicholas. I plan to make the street the subject of a future blog post.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 24mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/50

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Many people assume that an old road that is laid with stones is "cobbled" and that such stones are called "cobblestones". The word "setts" isn't widely known, but where it is, there is a general belief that it is synonymous with cobbles. However, the two types of stone road surface are different.

The essence of the distinction is as follows: cobblestones are found and setts are made. So, cobblestones may be - and often are - large (bigger than 2.5 inches but smaller than 10 inches), water-worn pebbles, that are laid closely together, frequently irregularly, but sometimes with patterns and borders. Setts are cut, rectangular, blocks of stone, usually granite, that are laid in stepped parallel courses, rather like a horizontal, stretcher bond, wall. An example of a road constructed of granite setts is shown in today's photograph which shows Pilot Street in King's Lynn, Norfolk. Such a road is very durable, looks great, with the slight differences in colour of the setts adding to its appeal, but is somewhat uncomfortable to walk, cycle and drive over. It is for the latter reason that many British cobbled roads and those laid with setts were taken up or covered with a smooth layer of tarmacadam. However, many survived, and quite a few of those that were buried have since been revealed and repaired.

This particular street in King's Lynn has a charming and interesting collection of houses spanning several centuries and on one side borders the churchyard of the town's second largest medieval church, St Nicholas. I plan to make the street the subject of a future blog post.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 24mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/50

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, December 14, 2012

Looking out of the window

click photo to enlarge

It's sometimes a welcome change when you don't have to actively search out photographs but instead they just appear when you look out of the window. Today's is a view from one of our upstairs windows, a scene that I spotted as I went to brush my teeth. I've always liked to photograph in fog. It's an experience that is often physically unpleasant but mentally stimulating. The way the suspended water droplets mute the colours, make objects less distinct, and can give a plain backdrop to a scene where it is usually busy and visually distracting, opens up new photographic possibilities.

In this shot all those factors came into play. However, it was the presence of the sun's dimmed disc that caused me to take the photograph. It offered both a sharp point of light as a visual focus and sufficient brightness to show off the skeletal trees. My first shot was of just those two elements. But, as I watched groups of wood pigeons fly out of the village trees and head out to the fields - brussel sprout tops are favoured at the moment - I thought that a group of them in the top left corner would add to the composition. It took a wait of a couple of minutes before some appeared, but when they did I took my shot. Wood pigeons are the one bird that is generally unwelcome in my garden. They cause significant damage to our vegetable garden and the cherry trees, and cause me to use wire netting as protection. So, it was a refreshing change to hope for and then welcome the presence of these rapacious birds.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 183mm

F No: f7.1 Shutter Speed: 1/250

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.00 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

It's sometimes a welcome change when you don't have to actively search out photographs but instead they just appear when you look out of the window. Today's is a view from one of our upstairs windows, a scene that I spotted as I went to brush my teeth. I've always liked to photograph in fog. It's an experience that is often physically unpleasant but mentally stimulating. The way the suspended water droplets mute the colours, make objects less distinct, and can give a plain backdrop to a scene where it is usually busy and visually distracting, opens up new photographic possibilities.

In this shot all those factors came into play. However, it was the presence of the sun's dimmed disc that caused me to take the photograph. It offered both a sharp point of light as a visual focus and sufficient brightness to show off the skeletal trees. My first shot was of just those two elements. But, as I watched groups of wood pigeons fly out of the village trees and head out to the fields - brussel sprout tops are favoured at the moment - I thought that a group of them in the top left corner would add to the composition. It took a wait of a couple of minutes before some appeared, but when they did I took my shot. Wood pigeons are the one bird that is generally unwelcome in my garden. They cause significant damage to our vegetable garden and the cherry trees, and cause me to use wire netting as protection. So, it was a refreshing change to hope for and then welcome the presence of these rapacious birds.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 183mm

F No: f7.1 Shutter Speed: 1/250

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.00 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, December 12, 2012

King's Lynn Custom House

click photo to enlarge

I've written about the Custom House at King's Lynn before. This distinguished building of 1683 is an outstanding structure in a town of many remarkable old buildings. What I haven't mentioned - because I didn't know it at the time - is that, though it was built in the latest restrained classical style showing the influence of both Christopher Wren and Dutch architecture, it also carried on an old tradition that is seen in many old, semi-public buildings. When the Custom House began its life (as a merchants' exchange) the rounded-headed, ground floor arches were open to the street in the same way that medieval guildhalls, town halls and grammar schools often were. The upstairs room, as with these precursors, was always enclosed, and it remains so today. When were the arches blocked up? I don't know, but it may well have been quite early in the building's history.

The classic view of the Custom House has either the dock basin and Purfleet Quay, or the statue of George Vancouver in the foreground. On my recent visit to the town, on a cold day with regular heavy showers, I looked for a different composition for the building. My first attempt was from a point near the pedimented doorway on the distant left of the photograph. However, the shot that I post today from further up the road, into the light, making the most of the sky, and with the gleam of water on the setts of the road and footpaths, works much better. I think it's a photograph that wouldn't work as well without the evidence of recent rain to enliven the foreground. The bicycle stands, though of little practical use in that particular location - I've never seen a bike fixed to them - also help to give the image some depth.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 17mm

F No: f11

Shutter Speed: 1/80

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: N/A

I've written about the Custom House at King's Lynn before. This distinguished building of 1683 is an outstanding structure in a town of many remarkable old buildings. What I haven't mentioned - because I didn't know it at the time - is that, though it was built in the latest restrained classical style showing the influence of both Christopher Wren and Dutch architecture, it also carried on an old tradition that is seen in many old, semi-public buildings. When the Custom House began its life (as a merchants' exchange) the rounded-headed, ground floor arches were open to the street in the same way that medieval guildhalls, town halls and grammar schools often were. The upstairs room, as with these precursors, was always enclosed, and it remains so today. When were the arches blocked up? I don't know, but it may well have been quite early in the building's history.

The classic view of the Custom House has either the dock basin and Purfleet Quay, or the statue of George Vancouver in the foreground. On my recent visit to the town, on a cold day with regular heavy showers, I looked for a different composition for the building. My first attempt was from a point near the pedimented doorway on the distant left of the photograph. However, the shot that I post today from further up the road, into the light, making the most of the sky, and with the gleam of water on the setts of the road and footpaths, works much better. I think it's a photograph that wouldn't work as well without the evidence of recent rain to enliven the foreground. The bicycle stands, though of little practical use in that particular location - I've never seen a bike fixed to them - also help to give the image some depth.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 17mm

F No: f11

Shutter Speed: 1/80

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: N/A

Tuesday, December 11, 2012

The masks slip further

click photo to enlarge

The UK's feeble coalition government is currently basking in a warm glow after months of limping along from one piece of bad news to another. They feel that George Osborne's Autumn Statement on the economy went much better than expected, that the Labour Party's response was poor, and that they can feel more confident about the public accepting the prospect of a triple dip recession and the fact that the government has missed virtually every economic target it set for itself. Moreover, in planning to introduce an unnecessary piece of legislation, the purpose of which is to further cut the state benefits received by what they call "shirkers" - the unemployed, low paid workers and the disabled - they feel that they have put Labour in the awkward position of having to vote against something that has quite a bit of popular support.

However, I think they have seriously misread the British people. In fact, such was the effect of the performance of David Cameron, George Osborne and Danny Alexander, I'd like to see an Autumn Statement every week. Why? Because Cameron and Osborne seem to have forgotten what they learnt from Tony Blair, namely that presentation is as important as content in these days of mass media coverage. What I saw in their delivery of the Autumn Statement was so much more than "two posh boys who don't know the price of milk", as one of their own MPs described the prime minister and chancellor. Certainly that remoteness from everyday life was evident in their policy proposals, but it was overlaid with what came across to me as sneering, scornful, guffawing contempt for everyone who opposed their programme and for the "shirkers" on the receiving end of it. The mask that they adopted before the election, and which remained in place for a few months afterwards, has been slowly slipping with every policy statement, every piece of legislation, every prime minister's question time and in every TV appearance. Last week it fell away almost completely and what was displayed came across as ugly, ignorant, spiteful and un-British. I seem to recall that this coalition promised a new kind of politics focused on what was best for the country, that eschewed the old "yah boo" slanging matches. How quickly that was forgotten and business as usual took its place. However, I have a strong feeling that the unedifying sight of the smirking coalition front bench fully revealing themselves (including Danny Alexander's "do I laugh out loud or don't I" equivocation) will linger long in the minds of the British public.

The chancellor of the exchequer, George Osborne, has been described as an "economic illiterate", and it is undoubtedly true that his Ayn Rand, Chicago school, "market knows best", "cut the state" prescription is one that has been deliberately ignored by those countries that have most effectively dealt with the current recession. But Osborne is also known as a consummate political plotter, the main strategist within the Conservative Party, who does nothing without measuring its influence on their chances of re-election. After Wednesday's performance perhaps it is also time for a blunt re-appraisal of his status as a master of the dark arts and a latter day Machiavelli.*

All of which has nothing to do with today's photograph of a group of mallards swimming across and spoiling the perfectly reflected trees in a pond at Swineshead, Lincolnshire. Though, in retrospect, it may have a bearing if they are lame ducks.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: LX3

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 12.8mm (60mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: 2.8

Shutter Speed: 1/125

ISO: 250

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

The UK's feeble coalition government is currently basking in a warm glow after months of limping along from one piece of bad news to another. They feel that George Osborne's Autumn Statement on the economy went much better than expected, that the Labour Party's response was poor, and that they can feel more confident about the public accepting the prospect of a triple dip recession and the fact that the government has missed virtually every economic target it set for itself. Moreover, in planning to introduce an unnecessary piece of legislation, the purpose of which is to further cut the state benefits received by what they call "shirkers" - the unemployed, low paid workers and the disabled - they feel that they have put Labour in the awkward position of having to vote against something that has quite a bit of popular support.

However, I think they have seriously misread the British people. In fact, such was the effect of the performance of David Cameron, George Osborne and Danny Alexander, I'd like to see an Autumn Statement every week. Why? Because Cameron and Osborne seem to have forgotten what they learnt from Tony Blair, namely that presentation is as important as content in these days of mass media coverage. What I saw in their delivery of the Autumn Statement was so much more than "two posh boys who don't know the price of milk", as one of their own MPs described the prime minister and chancellor. Certainly that remoteness from everyday life was evident in their policy proposals, but it was overlaid with what came across to me as sneering, scornful, guffawing contempt for everyone who opposed their programme and for the "shirkers" on the receiving end of it. The mask that they adopted before the election, and which remained in place for a few months afterwards, has been slowly slipping with every policy statement, every piece of legislation, every prime minister's question time and in every TV appearance. Last week it fell away almost completely and what was displayed came across as ugly, ignorant, spiteful and un-British. I seem to recall that this coalition promised a new kind of politics focused on what was best for the country, that eschewed the old "yah boo" slanging matches. How quickly that was forgotten and business as usual took its place. However, I have a strong feeling that the unedifying sight of the smirking coalition front bench fully revealing themselves (including Danny Alexander's "do I laugh out loud or don't I" equivocation) will linger long in the minds of the British public.

The chancellor of the exchequer, George Osborne, has been described as an "economic illiterate", and it is undoubtedly true that his Ayn Rand, Chicago school, "market knows best", "cut the state" prescription is one that has been deliberately ignored by those countries that have most effectively dealt with the current recession. But Osborne is also known as a consummate political plotter, the main strategist within the Conservative Party, who does nothing without measuring its influence on their chances of re-election. After Wednesday's performance perhaps it is also time for a blunt re-appraisal of his status as a master of the dark arts and a latter day Machiavelli.*

All of which has nothing to do with today's photograph of a group of mallards swimming across and spoiling the perfectly reflected trees in a pond at Swineshead, Lincolnshire. Though, in retrospect, it may have a bearing if they are lame ducks.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: LX3

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 12.8mm (60mm - 35mm equiv.)

F No: 2.8

Shutter Speed: 1/125

ISO: 250

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Monday, December 10, 2012

Eagle lecterns

click photo to enlarge

Visit any church and you will invariably find a lectern. These pedestals with an inclined tray at the top are designed to hold an open Bible from which a reading may be made during a service. In Church of England buildings these are usually free-standing, are placed on the other side of the chancel arch from the pulpit, and are based on one of the only two designs that have found widespread favour down the centuries.

The most basic form of lectern is a simple column made of wood or metal (usually brass) on top of which is a rectangular tray with a lip to prevent the Bible slipping from it. This tray may be plain or ornately pierced. The other model for the lectern - and by far the most popular - features a column, sometimes with clawed feet or small lions at the base and a ball at the top. Standing on the ball with outspread wings to form the inclined tray is an eagle. These too are made of wood or brass, with the metal version being most common. Many brass eagle lecterns are Victorian designs and may feature a dedicatory inscription noting the date and donor's name. The example shown in the smaller photograph is at Swineshead, Linconshire. It has as inscription of 1898. The elaborate red cover protects the Bible when it is not in use. Some eagle lecterns remain from the medieval period. These are the originals on which the Victorian restorers based their models. You can often work out the age of a metal eagle lectern by the degree to which the magnificent bird is accurately represented: the more it looks like a parrot, the older it is likely to be!

But, whilst lecterns have tended to follow these two basic designs, every now and again I come across one where the designer has sought to break free from this straight-jacket. One that immediately springs to mind is in the church of All Saints at Harmston, Lincolnshire. This has an angel with upstretched arms holding the inclined shelf above her head, Atlas-like. Today's photograph shows a detail of an example of the most common lectern design in the church at Folkingham, Lincolnshire.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 67mm

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/50

ISO: 3200

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Visit any church and you will invariably find a lectern. These pedestals with an inclined tray at the top are designed to hold an open Bible from which a reading may be made during a service. In Church of England buildings these are usually free-standing, are placed on the other side of the chancel arch from the pulpit, and are based on one of the only two designs that have found widespread favour down the centuries.

The most basic form of lectern is a simple column made of wood or metal (usually brass) on top of which is a rectangular tray with a lip to prevent the Bible slipping from it. This tray may be plain or ornately pierced. The other model for the lectern - and by far the most popular - features a column, sometimes with clawed feet or small lions at the base and a ball at the top. Standing on the ball with outspread wings to form the inclined tray is an eagle. These too are made of wood or brass, with the metal version being most common. Many brass eagle lecterns are Victorian designs and may feature a dedicatory inscription noting the date and donor's name. The example shown in the smaller photograph is at Swineshead, Linconshire. It has as inscription of 1898. The elaborate red cover protects the Bible when it is not in use. Some eagle lecterns remain from the medieval period. These are the originals on which the Victorian restorers based their models. You can often work out the age of a metal eagle lectern by the degree to which the magnificent bird is accurately represented: the more it looks like a parrot, the older it is likely to be!

But, whilst lecterns have tended to follow these two basic designs, every now and again I come across one where the designer has sought to break free from this straight-jacket. One that immediately springs to mind is in the church of All Saints at Harmston, Lincolnshire. This has an angel with upstretched arms holding the inclined shelf above her head, Atlas-like. Today's photograph shows a detail of an example of the most common lectern design in the church at Folkingham, Lincolnshire.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 67mm

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/50

ISO: 3200

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Saturday, December 08, 2012

Winter view of Walcot

click photo to enlarge

Walking in lowland Lincolnshire can be a mucky, sticky affair in winter. Arable land at this time of year is often wet and muddy and it's not uncommon to end a walk measuring a couple of inches taller than when you set off, such is the tenacity with which the soil clings to the sole of your boots. Consequently, a deep overnight frost is welcome because it means that fields which are usually impassable or unpleasant to walk, solidify and become much easier. In fact, the day we did a circular morning walk from Folkingham to Walcot, then on to Pickworth and finally back to Folkingham, the ground was like concrete and we left no footprints to mark our passage.

There is another feature of this walk that makes it a good choice for a winter walk and that is the greater than usual amount of pasture through which the footpaths meander. Permanent grass is reasonably common on Lincolnshire's higher land but less so lower down. In this area, especially around the villages, there is quite a bit that often has flocks of rather timid sheep or sometimes pet animals of the sort favoured by those who engage in "horsiculture."

The church at Walcot has become one of my favourite Lincolnshire churches. It suffered much less than many from the attentions of the restorers and enthusiasts, and what was done (mostly in 1907) was accomplished with sensitivity and respect for the achievements of the medieval builders and masons. The current congregation continues this work so when you enter the building you get a real sense of stepping into the past. Inside the fabric is mainly twelfth and thirteenth century, with the outside largely fourteenth century. I've posted photographs of the interior, the porch and the font before, but on the day of my visit the light wasn't bright enough for interior shots. However, I'd set out on this walk in the hope of returning with a landscape or two, and even though the weather deteriorated, the sun disappeared, and drab cloud rolled in, I managed this shot that features the broach spire of the distant church rising from the pantile roofs of the few farms and houses that constitute this small village.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 73mm

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/80

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Walking in lowland Lincolnshire can be a mucky, sticky affair in winter. Arable land at this time of year is often wet and muddy and it's not uncommon to end a walk measuring a couple of inches taller than when you set off, such is the tenacity with which the soil clings to the sole of your boots. Consequently, a deep overnight frost is welcome because it means that fields which are usually impassable or unpleasant to walk, solidify and become much easier. In fact, the day we did a circular morning walk from Folkingham to Walcot, then on to Pickworth and finally back to Folkingham, the ground was like concrete and we left no footprints to mark our passage.

There is another feature of this walk that makes it a good choice for a winter walk and that is the greater than usual amount of pasture through which the footpaths meander. Permanent grass is reasonably common on Lincolnshire's higher land but less so lower down. In this area, especially around the villages, there is quite a bit that often has flocks of rather timid sheep or sometimes pet animals of the sort favoured by those who engage in "horsiculture."

The church at Walcot has become one of my favourite Lincolnshire churches. It suffered much less than many from the attentions of the restorers and enthusiasts, and what was done (mostly in 1907) was accomplished with sensitivity and respect for the achievements of the medieval builders and masons. The current congregation continues this work so when you enter the building you get a real sense of stepping into the past. Inside the fabric is mainly twelfth and thirteenth century, with the outside largely fourteenth century. I've posted photographs of the interior, the porch and the font before, but on the day of my visit the light wasn't bright enough for interior shots. However, I'd set out on this walk in the hope of returning with a landscape or two, and even though the weather deteriorated, the sun disappeared, and drab cloud rolled in, I managed this shot that features the broach spire of the distant church rising from the pantile roofs of the few farms and houses that constitute this small village.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 73mm

F No: f5.6

Shutter Speed: 1/80

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, December 07, 2012

Staring at stairs

click photo to enlarge

When I looked in my edition of the Oxford English Dictionary I initially couldn't find the word "stairwell". But, after a bit of digging, it turned up towards the end of the "stair" entry. The definition was as I imagined, namely "the shaft containing a flight of stairs." It seems to be one of those words that is slowly falling out of use, being replaced by "stairs" and "staircase", neither of which properly describes the architectural space, but rather the structure for ascent and descent that it holds.

I was pondering this word as I processed my photograph of a glass-walled stairwell in some Hull offices, a shot that I'd taken during the early evening on my last visit to the Yorkshire city. It occurred to me that I had to - wait for it - "stare well" before I took my photograph, but that no one in the building took the slightest bit of notice of me. That was quite a contrast with what happened when I took an early evening photograph of a glass walled building in the private public space that is "More London" a couple of years ago. On that occasion a security guard came out and asked me to stop taking photographs. I thought then, as I thought when I took the photograph in Hull, that anyone who doesn't want to be photographed inside the building in which they work really shouldn't choose one with glass walls. If you inhabit a goldfish bowl you can't complain if people stand and look at you or take photographs, especially if the land outside is public space. Besides, doesn't an architect, in designing in this way, seek to both satisfy the practical and aesthetic needs of the client and offer the locality a building worth looking at? And can we be blamed if we look - or take photographs? Those in this office certainly seemed untroubled by me taking shots from nearby and further away. Would that London offices were as accommodating!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 80mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/80

ISO: 1000

Exposure Compensation: -1.00 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

When I looked in my edition of the Oxford English Dictionary I initially couldn't find the word "stairwell". But, after a bit of digging, it turned up towards the end of the "stair" entry. The definition was as I imagined, namely "the shaft containing a flight of stairs." It seems to be one of those words that is slowly falling out of use, being replaced by "stairs" and "staircase", neither of which properly describes the architectural space, but rather the structure for ascent and descent that it holds.

I was pondering this word as I processed my photograph of a glass-walled stairwell in some Hull offices, a shot that I'd taken during the early evening on my last visit to the Yorkshire city. It occurred to me that I had to - wait for it - "stare well" before I took my photograph, but that no one in the building took the slightest bit of notice of me. That was quite a contrast with what happened when I took an early evening photograph of a glass walled building in the private public space that is "More London" a couple of years ago. On that occasion a security guard came out and asked me to stop taking photographs. I thought then, as I thought when I took the photograph in Hull, that anyone who doesn't want to be photographed inside the building in which they work really shouldn't choose one with glass walls. If you inhabit a goldfish bowl you can't complain if people stand and look at you or take photographs, especially if the land outside is public space. Besides, doesn't an architect, in designing in this way, seek to both satisfy the practical and aesthetic needs of the client and offer the locality a building worth looking at? And can we be blamed if we look - or take photographs? Those in this office certainly seemed untroubled by me taking shots from nearby and further away. Would that London offices were as accommodating!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 80mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/80

ISO: 1000

Exposure Compensation: -1.00 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, December 05, 2012

Value for money and guitars

In a recent post I reflected on value for money with reference to cameras and coffee, but it's something I look for in everything I buy. There are those who believe that "you get what you pay for", implying that there is a direct and widespread correlation between price and quality. Though there is often such a link it is by no means always present, and it seems to apply less at the top of the market than in the middle or at the bottom. In my experience value for money often resides at points around the middle of the market, sometimes a bit below, at other times a bit above.

Given those views it will come as no surprise that a guitar I recently bought is not the cheapest available and by no means the most expensive. In fact I'd say its price resides somewhere below the average. However, in terms of value for money it is quite remarkable. The Washburn WD10SCE electro-acoustic replaces a much more expensive Epiphone guitar that I've had for thirty or so years. When I bought the old guitar I looked at what was available, tried several in the shop, and settled on the Epiphone. And, despite my research and hands-on experience, I've never been totally happy with it in terms of sound or action. I've tried different brands of string, different weights, adjusted the truss rod and much else, all to no avail. But I soldiered on using the guitar because it was good enough. Since I retired I've played my guitars much more and the desire for a change has become more pressing. So, on the basis of no trials, but going solely on other people's opinions and reviews, I bought the Washburn. After a few weeks of use I can say that I am very happy with the sound, the action, the quality of materials and workmanship. There is (or rather was) only one problem.

The guitar is supplied with just a single strap button. Now, like any guitar, it can be played without a strap. However, if you are going to put one button on a guitar (at the base of the body), then surely you'd put another at one of the usual locations somewhere around the point where the neck meets the shoulders of the body. I recognise that a strap that fixes at the supplied base button and which ties on just above the nut is a possibility. But, the way this guitar was sold it's the only possibility, one that is much less favoured today, and so why not offer a second stud - the cost is minimal - to give the buyer a wider choice of fixing positions? To cut a long story short, I mounted my own second button so that I can use a strap in the way I prefer. You can see it in the photograph in the top left corner. I could have fixed it to the side of the heel of the neck but I chose to use the side of the body. To make a secure fixing I first glued a block of hardwood inside to receive the screw. It has worked very well, the guitar is now as near to perfect as someone of my relatively limited abilities can hope for, and I'm looking forward to using it for the next thirty years or so!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 95mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/3

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.00 EV

Image Stabilisation: Off

Monday, December 03, 2012

Mock shop fronts

click photo to enlarge

One of the few growth industries in these depressed times is the mock shop front. These are either manufactured in printed form, ready to be applied to the protective boarding that is fixed to the empty property, or more often, hand-painted by a local artist/painter. I've noticed quite a few of these on my travels, and over the past few years the number has visibly increased.

The main reason for their appearance is the closure of town-centre businesses unable to continue trading due to the economic downturn, and the understandable unwillingness of local traders and councils to have their high streets blighted by too many obviously empty premises. Of course, the growth of out-of-town shopping centres with their plentiful, free parking closed high street shops well before the onset of the latest economic crisis. But, what was a managed decline has, since 2008, increased to the point where something had to be done. A mock shop front is clearly only a stop-gap measure, but longer-term solutions are slower to appear and so these representations are not entirely without value.

I've seen examples that are banal, amateurish and inventive. One or two have been obvious labours of love and quite admirable. Today's example, in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, falls somewhere in the middle of this range. It represents an old-style butcher's shop with a range of meats, pies, game etc. all priced using pre-decimal currency values. It's a facade I've wanted to photograph before, but only on my recent visit to the town was the view of it unimpeded by parked vehicles.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 50mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/320

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

One of the few growth industries in these depressed times is the mock shop front. These are either manufactured in printed form, ready to be applied to the protective boarding that is fixed to the empty property, or more often, hand-painted by a local artist/painter. I've noticed quite a few of these on my travels, and over the past few years the number has visibly increased.

The main reason for their appearance is the closure of town-centre businesses unable to continue trading due to the economic downturn, and the understandable unwillingness of local traders and councils to have their high streets blighted by too many obviously empty premises. Of course, the growth of out-of-town shopping centres with their plentiful, free parking closed high street shops well before the onset of the latest economic crisis. But, what was a managed decline has, since 2008, increased to the point where something had to be done. A mock shop front is clearly only a stop-gap measure, but longer-term solutions are slower to appear and so these representations are not entirely without value.

I've seen examples that are banal, amateurish and inventive. One or two have been obvious labours of love and quite admirable. Today's example, in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, falls somewhere in the middle of this range. It represents an old-style butcher's shop with a range of meats, pies, game etc. all priced using pre-decimal currency values. It's a facade I've wanted to photograph before, but only on my recent visit to the town was the view of it unimpeded by parked vehicles.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 50mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/320

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Sunday, December 02, 2012

Winter trees

click photo to enlarge

Winter trees - at least the deciduous variety - are different from the trees of spring, summer and autumn. In the more benign seasons they appear genial, softer, friendlier, more welcoming, a complement to their location. In winter, however, these trees seem to have a split personality. Looked at on a cold, clear day, with blue sky above, or seen against the warm glow of a sunrise or sunset, the tracery of twigs, branches and boughs charm the eye with their beauty and invite us to look more closely at them and admire their delicacy. However, on a cold, damp, grey foggy day, the wet, black, skeletal silhouettes can assume a severe, malign, even depressing, appearance.

I was thinking about this as I pointed my camera across a piece of waste ground in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, framing some factory chimneys and the smoke or steam that was issuing from them. The billowing, white clouds were being distressed and dispersed by the wind as they climbed from the stack and trailed across the dark clouds above. Should I move to my left and exclude the trees from my composition, or should I include them? I briefly tossed those thoughts back and forth in my head and decided that the trees, on this occasion, added a desolate touch that intensified the slightly grim prospect before me, and I took my shot. In summer they would add a welcome greenness, softening the location, offering towers of natural beauty in this urban setting where housing abutted the towers of industry. But, on this late November day, despite the sun breaking through the cloud cover, that welcome verdure was only a memory and a promise.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 105mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/400

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Winter trees - at least the deciduous variety - are different from the trees of spring, summer and autumn. In the more benign seasons they appear genial, softer, friendlier, more welcoming, a complement to their location. In winter, however, these trees seem to have a split personality. Looked at on a cold, clear day, with blue sky above, or seen against the warm glow of a sunrise or sunset, the tracery of twigs, branches and boughs charm the eye with their beauty and invite us to look more closely at them and admire their delicacy. However, on a cold, damp, grey foggy day, the wet, black, skeletal silhouettes can assume a severe, malign, even depressing, appearance.

I was thinking about this as I pointed my camera across a piece of waste ground in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, framing some factory chimneys and the smoke or steam that was issuing from them. The billowing, white clouds were being distressed and dispersed by the wind as they climbed from the stack and trailed across the dark clouds above. Should I move to my left and exclude the trees from my composition, or should I include them? I briefly tossed those thoughts back and forth in my head and decided that the trees, on this occasion, added a desolate touch that intensified the slightly grim prospect before me, and I took my shot. In summer they would add a welcome greenness, softening the location, offering towers of natural beauty in this urban setting where housing abutted the towers of industry. But, on this late November day, despite the sun breaking through the cloud cover, that welcome verdure was only a memory and a promise.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 105mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/400

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Saturday, December 01, 2012

Quirky portraits

click photo to enlarge

I used to take more portrait photographs than I do now. When our children were younger and lived with us they were very frequent subjects for my camera, as was my wife. Today I still take photographs of our children (and their significant others), and photographs of my wife are regular occurrences too, but in total numbers they are fewer than formerly. However, and perhaps understandably, our grand-daughter is the person I have photographed most in the past couple of years.

Good portrait photography has substance and value. And, though I appreciate and admire a well-done, insightful and inventive portrait, it's not a branch of photography that I've ever wanted to make a regular part of my photography: at least not to the extent of widening out beyond immediate family members. However, I do rather like constructing the occasional quirky portrait or self-portrait. This blog features more than a few of those - for example this one or perhaps this one, both of my wife, or this one of me. I suppose it's because I enjoy the creative challenge involved in imagining and constructing shots of this sort that I pursue them rather more than the formal portrait.