click photo to enlarge

Recently, as I was looking through my 2012 collection of photographs, I got to thinking about basic natural, seasonal colours. It seems to me that in a country such as ours green, blue, grey and white are colours that are constants throughout the year. Grass, sky, clouds and snow provide those. To these three staples winter adds the black of wet trees and the brown of dead vegetation. Spring injects the yellow and yellow-green of new growth into the mix. Autumn adds the tints of yellow, brown, orange and red of turning leaves. But it is summer when nature deploys the fullest colour palette. To all of the colours of the other seasons are added every other colour that nature offers. But more than that, it offers them in deeper hues. Consequently when in September autumn makes its presence first felt in subdued tones, longer shadows and the first chill in the air, I look at the colours around me with a sense of what I'm about to lose.

On a walk in mid-September at Market Deeping I stopped on the bridge over the River Welland and looked downstream at the trees overhanging the shallow water. The sun was shining and the light was bright and clear revealing every detail. The colours were deep and glowing with a touch of autumnal brown in some of the leaves. The view offered little in the way of a main subject but the mix of colours was beautiful and evocative of the summer that was beginning to pass out of reach. So I tried to hang on to it through the photograph I took.

A week earlier we'd been in Grantham and I took another photograph. It offered a nice contrast between the sharp angularity of the building and the irregularity of the planting. But it too offered that memory of summer. Here the flowers were starting to turn and the first fallen leaves of a silver birch were littering the grass. In a few short weeks the leaves would be gone and the flowers too. But the scene retained the essence of summer whilst at the same time prefiguring the autumn to come.

photographs and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 24mm

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/60

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Pages

▼

Sunday, September 30, 2012

Friday, September 28, 2012

321 Triptych

My blog post on the last day of 2009 featured three photographs presented in the form of a triptych. For anyone who doesn't know, a triptych is either a single picture divided into three parts but joined together or three different pictures joined together. In each case they are presented as a whole. I first came across the term when studying Renaissance painting. Often the reredos of an altar was in the form of a painted triptych of the Crucifixion, Nativity or Annunciation, that could be folded up when the altar wasn't in use. The Victorians made the religious triptych fashionable again, and they are still being produced today in one form or another for secular as well as church purposes.

My first triptych was intensely secular: how else can you describe photographs of the detergent and grease left on the roasting tray as I cleaned it after the Christmas meal? The same can be said of today's photograph(s) - my second foray into the world of the triptych. I'd taken a photograph of the number on a new sign that indicated the floor of a building that I was in. As I ascended the stairs in the stairwell I discovered that a different colour had been used for the walls of each floor. So, with the idea of a triptych in mind I made sure I got a shot of the numbers for the floors of the first, second and third storeys. The glass or plastic that the signs were made from reflected the windows and stairs, and I made sure to include these reflections. What appealed to me about these images was the high gloss and the sharp, clear delineation of the numbers contrasted with the out of focus softness ofthe reflections. The sequence - either ascending or descending - seemed the obvious way to sequence them.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1 (i.e. 3!)

Camera: Lumix LX3

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 7.9mm (37mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f2.4

Shutter Speed: 1/50

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, September 26, 2012

A shop and bull story

click photo to enlarge

Anyone who frequents photography websites cannot fail to have come across the oft repeated aphorism, "the best camera is the one you have with you." And, like most home-spun wisdom it contains an element of truth, for, if you come upon a potential photograph and are carrying even a modest camera you'll return home with an image. But, if you have the latest whizz-bang, high tech, zillion megapixel marvel at home but no camera with you then the potential image becomes like the fisherman's "one that got away": a photograph that was missed but which becomes ever more marvellous in every re-telling of the tale.

It's no surprise therefore that as well as selling DSLR cameras most manufacturers market one or more "enthusiast" or "professional" compact cameras, one purpose of which is to accompany the enthusiast or pro when the main camera can't be available. My Lumix LX3 has fulfilled this role for a few years and it was with me on the morning that I took today's photograph. We weren't out on a photographic expedition but doing our weekly shopping. After a cup of coffee we set off through the market and came upon a lorry from which, under a canopy at the side, meat was being sold. The back of the trailer featured a beautifully executed trompe l'oeil image of a black bull in a wooden enclosure, standing there in all its imperious might, eyes fixed on the passing public. One of the best touches of the artwork was the metal shutters and catch at the top that made it look like the back had been rolled up. The photographic possibilities of this striking image were immediately obvious and I started taking shots, trying to include a person to the left, right or passing in front. I got several and we went on our way. But, after a few minutes I decided that a person standing in front and looking up at the bull might make a good composition so we went back and my wife became that person.

When I reviewed my shots on the computer at home it became obvious that the first shot I took was the best. Another aphorism (of my invention) had clearly come into play, namely that "usually the best shot that you take of a subject is either the first or second, and subsequent attempts rarely match up to these." This has been the case with me for a long time. Perhaps I've photographed sufficiently frequently for intuition, my subconscious or my accumulated experience over more than forty years picture taking, to enable me to see shots quickly. Whatever the reason it has happened often enough for me to notice the phenomenon, though clearly not enough for me to learn the lesson and desist after my initial exposures!

For a couple more of my trompe l'oeil photographs see here and here.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Lumix LX3

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 11.1mm (52mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f4

Shutter Speed: 1/400

ISO: 80

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Anyone who frequents photography websites cannot fail to have come across the oft repeated aphorism, "the best camera is the one you have with you." And, like most home-spun wisdom it contains an element of truth, for, if you come upon a potential photograph and are carrying even a modest camera you'll return home with an image. But, if you have the latest whizz-bang, high tech, zillion megapixel marvel at home but no camera with you then the potential image becomes like the fisherman's "one that got away": a photograph that was missed but which becomes ever more marvellous in every re-telling of the tale.

It's no surprise therefore that as well as selling DSLR cameras most manufacturers market one or more "enthusiast" or "professional" compact cameras, one purpose of which is to accompany the enthusiast or pro when the main camera can't be available. My Lumix LX3 has fulfilled this role for a few years and it was with me on the morning that I took today's photograph. We weren't out on a photographic expedition but doing our weekly shopping. After a cup of coffee we set off through the market and came upon a lorry from which, under a canopy at the side, meat was being sold. The back of the trailer featured a beautifully executed trompe l'oeil image of a black bull in a wooden enclosure, standing there in all its imperious might, eyes fixed on the passing public. One of the best touches of the artwork was the metal shutters and catch at the top that made it look like the back had been rolled up. The photographic possibilities of this striking image were immediately obvious and I started taking shots, trying to include a person to the left, right or passing in front. I got several and we went on our way. But, after a few minutes I decided that a person standing in front and looking up at the bull might make a good composition so we went back and my wife became that person.

When I reviewed my shots on the computer at home it became obvious that the first shot I took was the best. Another aphorism (of my invention) had clearly come into play, namely that "usually the best shot that you take of a subject is either the first or second, and subsequent attempts rarely match up to these." This has been the case with me for a long time. Perhaps I've photographed sufficiently frequently for intuition, my subconscious or my accumulated experience over more than forty years picture taking, to enable me to see shots quickly. Whatever the reason it has happened often enough for me to notice the phenomenon, though clearly not enough for me to learn the lesson and desist after my initial exposures!

For a couple more of my trompe l'oeil photographs see here and here.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Lumix LX3

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 11.1mm (52mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f4

Shutter Speed: 1/400

ISO: 80

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Tuesday, September 25, 2012

Hazel trees and nuts

click photo to enlarge

In the "wildwood", the entirely natural woodland of c.4,500 B.C. that was unaffected by Neolithic or later peoples, hazel (Corylus avellana) was a prominent tree. It had been one of the first trees to colonise Britain's warming land as the Ice Age came to an end. In time, along with the oak it became the dominant species of much of upland England, southern Scotland, Wales and Dartmoor. It was found elsewhere, but not in the same numbers. But, the steadily rising temperatures encouraged the growth of pine, elm, oak and lime, and these trees overwhelmed the smaller hazel. It did continue to find a place along the edge of forests and in clearings, its nuts distributed by jays, red squirrels, wild boars and other birds and mammals, but it lost its former dominance.

The hazel is the only native British tree that produces nuts (the chestnut and walnut are introduced species). As such it has always been a food source for people, and cultivated varieties such as the Kentish Cob have been bred. In early and medieval times its supple wood was harvested from coppiced trees for use as wattle, hurdles, thatching sticks, hedging poles, fish traps and much else. The thicker branches were used for shepherds' crooks and walking sticks. However, changes in woodland management and farming led to there being only 114,000 acres of hazel coppice by 1945, and today very little of that survives. A further cause of the decline of hazel was the introduction of the grey squirrel in the nineteenth century. These animals can clear trees of all their nuts in September, only some of which they eat. Those that they bury don't usually germinate because at that time of year they are insufficiently ripe. The result is that today, after the elm, the hazel is the most seriously threatened native tree in Britain.

Contrary to popular belief trees do feature in the Lincolnshire Fens. Where I live there is a variety of species, some native such as the lime, others, like the horse chestnut, introduced. Moreover, there are hazel trees. The other day, whilst collecting sloes from the blackthorn bushes we gathered a few ripening hazel nuts to store, further ripen and sample in a few months time. Grey squirrels are common in the villages and small woods of the Fens, but the relatively isolated place where we found these hazel trees is one where I've never seen these destructive mammals (though we did see a jay). In fact, some of the hazel nuts were fully ripe and beginning to fall so perhaps there's a good chance that they'll further propagate the species in this locality. Never one to miss the opportunity of a photograph I picked a small nut cluster with leaves attached and took this rather botanical looking shot in natural light at home.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 100mm macro

F No: f13

Shutter Speed: 0.3 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: +0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

In the "wildwood", the entirely natural woodland of c.4,500 B.C. that was unaffected by Neolithic or later peoples, hazel (Corylus avellana) was a prominent tree. It had been one of the first trees to colonise Britain's warming land as the Ice Age came to an end. In time, along with the oak it became the dominant species of much of upland England, southern Scotland, Wales and Dartmoor. It was found elsewhere, but not in the same numbers. But, the steadily rising temperatures encouraged the growth of pine, elm, oak and lime, and these trees overwhelmed the smaller hazel. It did continue to find a place along the edge of forests and in clearings, its nuts distributed by jays, red squirrels, wild boars and other birds and mammals, but it lost its former dominance.

The hazel is the only native British tree that produces nuts (the chestnut and walnut are introduced species). As such it has always been a food source for people, and cultivated varieties such as the Kentish Cob have been bred. In early and medieval times its supple wood was harvested from coppiced trees for use as wattle, hurdles, thatching sticks, hedging poles, fish traps and much else. The thicker branches were used for shepherds' crooks and walking sticks. However, changes in woodland management and farming led to there being only 114,000 acres of hazel coppice by 1945, and today very little of that survives. A further cause of the decline of hazel was the introduction of the grey squirrel in the nineteenth century. These animals can clear trees of all their nuts in September, only some of which they eat. Those that they bury don't usually germinate because at that time of year they are insufficiently ripe. The result is that today, after the elm, the hazel is the most seriously threatened native tree in Britain.

Contrary to popular belief trees do feature in the Lincolnshire Fens. Where I live there is a variety of species, some native such as the lime, others, like the horse chestnut, introduced. Moreover, there are hazel trees. The other day, whilst collecting sloes from the blackthorn bushes we gathered a few ripening hazel nuts to store, further ripen and sample in a few months time. Grey squirrels are common in the villages and small woods of the Fens, but the relatively isolated place where we found these hazel trees is one where I've never seen these destructive mammals (though we did see a jay). In fact, some of the hazel nuts were fully ripe and beginning to fall so perhaps there's a good chance that they'll further propagate the species in this locality. Never one to miss the opportunity of a photograph I picked a small nut cluster with leaves attached and took this rather botanical looking shot in natural light at home.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 100mm macro

F No: f13

Shutter Speed: 0.3 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: +0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Monday, September 24, 2012

Ye Olde Red Lion, Bicker

click photo to enlarge

In England in 1665 the Great Plague, the last widespread outbreak of the feared bubonic plague, began killing about 100,000 people, mainly in London, but also across the rest of the country. The same year Robert Hooke's Micrographia, a book detailing his observations through lenses and microscopes, became the first publication of the Royal Society. In the American colonies the City of New Amsterdam was incorporated in the newly named city and territory of New York. And in the small Lincolnshire village of Bicker a new public house (pub), Ye Olde Red Lion, was built by John Drury who had his name and the date carved in a small panel at the top of the central gable.

That building still stands today. It is currently coming to the end of a comprehensive refurbishment and will soon re-open after having been closed for a couple of years. In these straitened times it is heartening to find a pub that has escaped the fate of most that close for lack of custom - namely dilapidation and possibly conversion to an entirely different use. It is also good to see a pub escape the clutches of a "pubco" and be taken on by a local entrepreneur. Ye Olde Red Lion, like many village pubs, has a long history in the community, and the continuation and re-vitalisation of this venerable building is something to celebrate.

The building itself is a Grade II Listed structure described as being in the "Fen Artisan Mannerist style" i.e. the work of the kind of local builder who constructed in the current and traditional way, occasionally adding a few idiosyncratic flourishes of his own. The basic structure is brick laid in an English bond (alternating courses of headers and stretchers), rusticated quoins at the corners, gable bands, a rudimentary pinnacle on the central gable, and all covered with render. Was it always rendered? The quoins suggest probably not, but it's difficult to tell when the coating was added. The nineteenth and twentieth century additions weren't always sympathetic, but original beams and roof timbers still remain inside.

Incidentally, the "Red Lion" is one of the most common pub names in the country, coming either first or second in the two most commonly cited lists. Its origins are not fully known, but a lion is a common heraldic device appearing in the coats arms of John of Gaunt, the House of Lancaster, Scotland and many families of lesser nobility. The Bicker pub's newly hung sign shows a heraldic red lion rampant with the date 1665.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 32mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/400

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

In England in 1665 the Great Plague, the last widespread outbreak of the feared bubonic plague, began killing about 100,000 people, mainly in London, but also across the rest of the country. The same year Robert Hooke's Micrographia, a book detailing his observations through lenses and microscopes, became the first publication of the Royal Society. In the American colonies the City of New Amsterdam was incorporated in the newly named city and territory of New York. And in the small Lincolnshire village of Bicker a new public house (pub), Ye Olde Red Lion, was built by John Drury who had his name and the date carved in a small panel at the top of the central gable.

That building still stands today. It is currently coming to the end of a comprehensive refurbishment and will soon re-open after having been closed for a couple of years. In these straitened times it is heartening to find a pub that has escaped the fate of most that close for lack of custom - namely dilapidation and possibly conversion to an entirely different use. It is also good to see a pub escape the clutches of a "pubco" and be taken on by a local entrepreneur. Ye Olde Red Lion, like many village pubs, has a long history in the community, and the continuation and re-vitalisation of this venerable building is something to celebrate.

The building itself is a Grade II Listed structure described as being in the "Fen Artisan Mannerist style" i.e. the work of the kind of local builder who constructed in the current and traditional way, occasionally adding a few idiosyncratic flourishes of his own. The basic structure is brick laid in an English bond (alternating courses of headers and stretchers), rusticated quoins at the corners, gable bands, a rudimentary pinnacle on the central gable, and all covered with render. Was it always rendered? The quoins suggest probably not, but it's difficult to tell when the coating was added. The nineteenth and twentieth century additions weren't always sympathetic, but original beams and roof timbers still remain inside.

Incidentally, the "Red Lion" is one of the most common pub names in the country, coming either first or second in the two most commonly cited lists. Its origins are not fully known, but a lion is a common heraldic device appearing in the coats arms of John of Gaunt, the House of Lancaster, Scotland and many families of lesser nobility. The Bicker pub's newly hung sign shows a heraldic red lion rampant with the date 1665.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 32mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/400

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Saturday, September 22, 2012

Apothecaries, memorials and words

click photo to enlarge

I've long been fascinated by the way that a word can fall out of use. In a blog post of 2009 I reflected on the demise during my lifetime of "aerodrome", "palings" and "petticoat". Today I've been thinking about another word that is much less used than formerly - "apothecary".

Walk down a high street today and you are very unlikely to see a shop sign advertising the services of an apothecary. However, had you trod the same route in the 1700s or 1800s such a business could well have been present. The nearest we get today to the apothecary of those centuries is the dispensing chemist or pharmacist. The first apothecaries in Britain were grocers specialising in non-perishable commodities such as preserves, wine, spices, herbs, medicinal drugs etc. In 1617 the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries was established in London following a split from the Grocers. They established a hall in Blackfriars, and until 1922 manufactured and sold pharmaceutical products there. In 1704 the Society won an important legal decision against the Royal College of Physicians which allowed them to prescribe and dispense medicines, an action that led to apothecaries evolving into practitioners of medicine as we know them today. And yet, despite this complicated background history, today most people who know the term "apothecary" associate it with the dispensing of medicine rather than the deployment of general medical skills.

Today's photograph commemorates the death in 1780, at the young age of thirty one years, of John Rugeley, an apothecary of Folkingham, Lincolnshire. Apparently he died of "the fever" - which one I don't know. His attractive slate tablet displays the florid script, flourishes and motifs that can be seen on many such memorials in this part of the county, here the work of "Casswell, Sculpt." It can be found in the village on the wall of the south aisle of St Andrew's church.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 65mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/15

ISO: 3200

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

I've long been fascinated by the way that a word can fall out of use. In a blog post of 2009 I reflected on the demise during my lifetime of "aerodrome", "palings" and "petticoat". Today I've been thinking about another word that is much less used than formerly - "apothecary".

Walk down a high street today and you are very unlikely to see a shop sign advertising the services of an apothecary. However, had you trod the same route in the 1700s or 1800s such a business could well have been present. The nearest we get today to the apothecary of those centuries is the dispensing chemist or pharmacist. The first apothecaries in Britain were grocers specialising in non-perishable commodities such as preserves, wine, spices, herbs, medicinal drugs etc. In 1617 the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries was established in London following a split from the Grocers. They established a hall in Blackfriars, and until 1922 manufactured and sold pharmaceutical products there. In 1704 the Society won an important legal decision against the Royal College of Physicians which allowed them to prescribe and dispense medicines, an action that led to apothecaries evolving into practitioners of medicine as we know them today. And yet, despite this complicated background history, today most people who know the term "apothecary" associate it with the dispensing of medicine rather than the deployment of general medical skills.

Today's photograph commemorates the death in 1780, at the young age of thirty one years, of John Rugeley, an apothecary of Folkingham, Lincolnshire. Apparently he died of "the fever" - which one I don't know. His attractive slate tablet displays the florid script, flourishes and motifs that can be seen on many such memorials in this part of the county, here the work of "Casswell, Sculpt." It can be found in the village on the wall of the south aisle of St Andrew's church.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 65mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/15

ISO: 3200

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, September 21, 2012

The Humber Bridge and dog walkers

click photo to enlarge

One thing that is very helpful when you are photographing in large spaces such as the seashore, by a big river, in open fields or in any other expanse, is a sense of the size or scale of the view. The same is true when your shot includes anything large or something that is difficult to visually "read" in a photograph: cliffs are a good example. Scale in this sense is an understanding of dimensions. Anyone familiar with photographs taken by geologists of rocks or embedded fossils will recognise the importance of the often included hammer or short ruler in helping the viewer to appreciate the size of what they are seeing. Those items don't have much use in general photography. However, there are many things that can offer a sense of scale where it is needed. In the past I've used a bench, a fence, a tree, cows, sheep and much else. Anything that is familiar to the viewer and which can therefore be used as a size indicator is all that is needed. Of course, the very best of indicators is the human figure. Place a person in a photograph and not only will he or she often be the initial point of interest for the viewer, they will immediately lend a sense of scale to the depicted scene.

Britain is known for being a nation of animal lovers. I count myself as one, though not in the sense that it is usually meant. My preference is not for the cats, dogs and the other kinds of domestic pets that are far too commonly found on these islands. As far as they are concerned I wish they were much fewer in number than is the case; a sentiment not widely shared or welcomed. My liking is for wildlife. The existence of animals that kill wildlife in very large numbers (cats) or are significant disturbers of the it (dogs) is something that I regret. But, I have to admit that there is a time when I find the presence of dogs and their owners useful, and that is as objects offering scale in my photographs. Today's shot does, I think, benefit from the dog walkers and their animal by the water's edge. Those small figures underline the enormous size of the Humber Bridge arching across the river above them. Take them away and the sense of the size of the engineering is substantially lessened and the force of the photograph diminished.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 24mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/1250

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

One thing that is very helpful when you are photographing in large spaces such as the seashore, by a big river, in open fields or in any other expanse, is a sense of the size or scale of the view. The same is true when your shot includes anything large or something that is difficult to visually "read" in a photograph: cliffs are a good example. Scale in this sense is an understanding of dimensions. Anyone familiar with photographs taken by geologists of rocks or embedded fossils will recognise the importance of the often included hammer or short ruler in helping the viewer to appreciate the size of what they are seeing. Those items don't have much use in general photography. However, there are many things that can offer a sense of scale where it is needed. In the past I've used a bench, a fence, a tree, cows, sheep and much else. Anything that is familiar to the viewer and which can therefore be used as a size indicator is all that is needed. Of course, the very best of indicators is the human figure. Place a person in a photograph and not only will he or she often be the initial point of interest for the viewer, they will immediately lend a sense of scale to the depicted scene.

Britain is known for being a nation of animal lovers. I count myself as one, though not in the sense that it is usually meant. My preference is not for the cats, dogs and the other kinds of domestic pets that are far too commonly found on these islands. As far as they are concerned I wish they were much fewer in number than is the case; a sentiment not widely shared or welcomed. My liking is for wildlife. The existence of animals that kill wildlife in very large numbers (cats) or are significant disturbers of the it (dogs) is something that I regret. But, I have to admit that there is a time when I find the presence of dogs and their owners useful, and that is as objects offering scale in my photographs. Today's shot does, I think, benefit from the dog walkers and their animal by the water's edge. Those small figures underline the enormous size of the Humber Bridge arching across the river above them. Take them away and the sense of the size of the engineering is substantially lessened and the force of the photograph diminished.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 24mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/1250

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, September 19, 2012

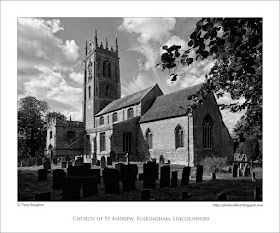

Jackdaws and church towers

click photo to enlarge

My upbringing in the Yorkshire Dales market town of Settle familiarised me with the jackdaw (Corvus monedula). The area is well-known for its rugged hills, sheep farming, limestone cliffs and stone-built houses. All of these combine to provide a fine habitat for this small crow. What one notices from everyday contact with the bird is not only its black plumage, its grey nape and its bright eye that give it a look of intelligence that it doesn't quite deserve, but also its characteristic call. This is usually described in writing as a sharp "chak" or a more drawn out "chaka-chaka-chak", a sound that accounts for the first part of the bird's name. In the Dales it builds its nest in holes and cavities on cliffs, in trees and in buildings.

When I lived in the city of Kingston upon Hull the jackdaw wasn't particularly noticeable though could be found. It was much more common in the surrounding countryside. During my time on Lancashire's Fylde Coast it became very familiar once more, and I often heard its distinctive cry as groups flew over my house. In the Lincolnshire Fens the bird is very common, associating with rooks to feed on stubble, around farms and in villages. It finds nest sites in trees, farm buildings and around house roofs. However, the plentiful medieval churches, especially the space behind the louvred openings of the bell towers, provide favoured sites for nests. The jackdaw has to compete with pigeons and doves (and the occasional peregrine falcon) for the best locations, but anyone who stands in a churchyard is almost bound to see jackdaws circling the church tower, entering through holes and making their cry echo from the old stonework.

Today's photograph shows the medieval church of St Andrew at Folkingham in Lincolnshire. Looking at the specks in the sky to the right of the tower top the critical observer might be forgiven for wondering whether my sensor needs cleaning or if I've got dust on the back of my lens. However, anyone who has read this far will realise that it is a circling crowd of jackdaws. My presence below disturbed them, but they soon settled and peered down at me as I picked my way through the gravestones to take a few more shots from my favoured south-east corner of the churchyard. Incidentally this photograph is a crop from the top half of a portrait-format shot. I find this method is a useful way of getting reasonably upright verticals in the absence of an expensive tilt-shift lens.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 19mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/400

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

My upbringing in the Yorkshire Dales market town of Settle familiarised me with the jackdaw (Corvus monedula). The area is well-known for its rugged hills, sheep farming, limestone cliffs and stone-built houses. All of these combine to provide a fine habitat for this small crow. What one notices from everyday contact with the bird is not only its black plumage, its grey nape and its bright eye that give it a look of intelligence that it doesn't quite deserve, but also its characteristic call. This is usually described in writing as a sharp "chak" or a more drawn out "chaka-chaka-chak", a sound that accounts for the first part of the bird's name. In the Dales it builds its nest in holes and cavities on cliffs, in trees and in buildings.

When I lived in the city of Kingston upon Hull the jackdaw wasn't particularly noticeable though could be found. It was much more common in the surrounding countryside. During my time on Lancashire's Fylde Coast it became very familiar once more, and I often heard its distinctive cry as groups flew over my house. In the Lincolnshire Fens the bird is very common, associating with rooks to feed on stubble, around farms and in villages. It finds nest sites in trees, farm buildings and around house roofs. However, the plentiful medieval churches, especially the space behind the louvred openings of the bell towers, provide favoured sites for nests. The jackdaw has to compete with pigeons and doves (and the occasional peregrine falcon) for the best locations, but anyone who stands in a churchyard is almost bound to see jackdaws circling the church tower, entering through holes and making their cry echo from the old stonework.

Today's photograph shows the medieval church of St Andrew at Folkingham in Lincolnshire. Looking at the specks in the sky to the right of the tower top the critical observer might be forgiven for wondering whether my sensor needs cleaning or if I've got dust on the back of my lens. However, anyone who has read this far will realise that it is a circling crowd of jackdaws. My presence below disturbed them, but they soon settled and peered down at me as I picked my way through the gravestones to take a few more shots from my favoured south-east corner of the churchyard. Incidentally this photograph is a crop from the top half of a portrait-format shot. I find this method is a useful way of getting reasonably upright verticals in the absence of an expensive tilt-shift lens.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 19mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/400

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -1.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Tuesday, September 18, 2012

Ovum for Poultry

click photo to enlarge

When, in the nineteenth century and first seventy five years or so of the twentieth century, manufacturers came to name a new product they frequently delved into Latin or Greek for their inspiration. From these ancient languages they would take a whole word, a part word or a combination of these and from them coin a new word that had a bearing on what it was that they wanted to name. Examples are many:

Today's photograph shows an enamelled metal advertisement that probably dates from the first half of the last century. It is fixed to an old agricultural building and advertises Joseph Thorley's feed for hens. This was called, appropriately, "Ovum", from the Latin for "egg". Knowing that, what do you imagine the company called the food they sold for rabbits? Here's a clue: the Latin name for the common rabbit is Oryctolagus cuniculus. Bearing that in mind they very sensibly called their rabbit food "Rabbitum"!

These days, of course, names are plucked from the fevered imagination of a twenty something advertising or marketing executive. You want to name a bookseller? Call it Amazon. How about a bank? Goldfish or Egg will do. A telecoms company? What about Everything Everywhere, surely one of the most ludicrous formulations of recent years, or perhaps any year! Today it sometimes seems that it's a virtue to make the company name have absolutely nothing to do with the organisation that it stands for. That being the case one wonders why brand names aren't chosen by opening the dictionary at random and selecting the first noun on the page. But then again, perhaps they are.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Lumix LX3

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 8.8mm (41mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f2.5

Shutter Speed: 1/100

ISO: 80

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

When, in the nineteenth century and first seventy five years or so of the twentieth century, manufacturers came to name a new product they frequently delved into Latin or Greek for their inspiration. From these ancient languages they would take a whole word, a part word or a combination of these and from them coin a new word that had a bearing on what it was that they wanted to name. Examples are many:

- automobile - from Greek autos (self) and Latin mobilis (to move)

- submarine - from Latin sub meaning "under" and marinus meaning "of the sea"

- Volvo - from Latin volvere (I roll) - the parent SFK company also made ball-bearings

- Sony - based on the Latin sonus (sound)

- Nike - from the name of the Greek goddess of victory

- Xerox - from xerography which uses the Greek xeros (dry) and graphos (writing)

Today's photograph shows an enamelled metal advertisement that probably dates from the first half of the last century. It is fixed to an old agricultural building and advertises Joseph Thorley's feed for hens. This was called, appropriately, "Ovum", from the Latin for "egg". Knowing that, what do you imagine the company called the food they sold for rabbits? Here's a clue: the Latin name for the common rabbit is Oryctolagus cuniculus. Bearing that in mind they very sensibly called their rabbit food "Rabbitum"!

These days, of course, names are plucked from the fevered imagination of a twenty something advertising or marketing executive. You want to name a bookseller? Call it Amazon. How about a bank? Goldfish or Egg will do. A telecoms company? What about Everything Everywhere, surely one of the most ludicrous formulations of recent years, or perhaps any year! Today it sometimes seems that it's a virtue to make the company name have absolutely nothing to do with the organisation that it stands for. That being the case one wonders why brand names aren't chosen by opening the dictionary at random and selecting the first noun on the page. But then again, perhaps they are.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Lumix LX3

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 8.8mm (41mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f2.5

Shutter Speed: 1/100

ISO: 80

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Monday, September 17, 2012

Holidays, escapes and everyday life

click photo to enlarge

Have you noticed how holidays are now frequently described as an "escape"? In some journalism and advertising the two words have become synonymous. There are travel companies that actually use the word in their company's name - "Escape Holidays", "Great Escape Holidays", "Island Escape Holidays". It makes them sound like organisations dedicated to springing prisoners from their incarceration, an image that the word "getaway" in connection with holidays only reinforces. The use of such language has troubled me for a while because of what it implies; namely that the everyday life of a person, couple or family is so damnably dreary, hard, depressing or lacking in joy, that a holiday is like a release from a living hell. Moreover, tied up with this is the idea that an effective and desirable break can only be achieved by shelling out a large amount of money, jumping on an aeroplane or boat, and fleeing to some foreign, preferably hot, land. It's an approach that I liken to the notion of going to a gym because you don't get enough exercise. It seems to me self-evident that fitness (see this post for my views on the misuse of this word!) comes from building exercise and sensible eating into your daily life, not bolting it on as an afterthought designed to compensate for what is clearly lacking. Similarly, shouldn't we be trying to organise our lives in such as way that each day offers us some pleasure, achievement, satisfaction - call it what you will - that cumulatively leads to us getting enjoyment from every single day? It's difficult if you are on the breadline, but much more realisable than might be imagined if you're not. Achieve it and the idea of catharsis through an "escape" seems ridiculous.

The misuse of that word came to mind when I was looking at my photograph of the narrow boats and cruisers tied up on the River Trent in Newark, Nottinghamshire. It's a photograph taken at a time that is described as either the end of summer or the beginning of autumn. There was a time when my wife and I idly considered the purchase of such a vessel. However, it didn't take us long to work out that, for us, being restricted to navigable waterways would be too limiting. I'm sure others think this too. I'm equally sure that many people find chugging along Britain's canals and rivers a fine way to pass the time or take a holiday. For us however, it would be too confining and we'd just have to escape!

For more thoughts touching on holidays see these posts - from 2005, and from 2009.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 161mm

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/200

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Have you noticed how holidays are now frequently described as an "escape"? In some journalism and advertising the two words have become synonymous. There are travel companies that actually use the word in their company's name - "Escape Holidays", "Great Escape Holidays", "Island Escape Holidays". It makes them sound like organisations dedicated to springing prisoners from their incarceration, an image that the word "getaway" in connection with holidays only reinforces. The use of such language has troubled me for a while because of what it implies; namely that the everyday life of a person, couple or family is so damnably dreary, hard, depressing or lacking in joy, that a holiday is like a release from a living hell. Moreover, tied up with this is the idea that an effective and desirable break can only be achieved by shelling out a large amount of money, jumping on an aeroplane or boat, and fleeing to some foreign, preferably hot, land. It's an approach that I liken to the notion of going to a gym because you don't get enough exercise. It seems to me self-evident that fitness (see this post for my views on the misuse of this word!) comes from building exercise and sensible eating into your daily life, not bolting it on as an afterthought designed to compensate for what is clearly lacking. Similarly, shouldn't we be trying to organise our lives in such as way that each day offers us some pleasure, achievement, satisfaction - call it what you will - that cumulatively leads to us getting enjoyment from every single day? It's difficult if you are on the breadline, but much more realisable than might be imagined if you're not. Achieve it and the idea of catharsis through an "escape" seems ridiculous.

The misuse of that word came to mind when I was looking at my photograph of the narrow boats and cruisers tied up on the River Trent in Newark, Nottinghamshire. It's a photograph taken at a time that is described as either the end of summer or the beginning of autumn. There was a time when my wife and I idly considered the purchase of such a vessel. However, it didn't take us long to work out that, for us, being restricted to navigable waterways would be too limiting. I'm sure others think this too. I'm equally sure that many people find chugging along Britain's canals and rivers a fine way to pass the time or take a holiday. For us however, it would be too confining and we'd just have to escape!

For more thoughts touching on holidays see these posts - from 2005, and from 2009.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 161mm

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/200

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Saturday, September 15, 2012

Reflecting on hats

click photo to enlarge

It's not only fashions in hats that come and go, hats themselves fall in and out of favour. When I was a callow youth the trilby and other styles of men's hats with brims were on the way out. Flat caps were following a similar course to near extinction, being favoured by older folk only. One hat that was worn by a few men, and which is rarely seen as daily wear now, was the beret. Some men had got into the habit of wearing one during the war, and continued (without the badge) when they returned to "civvy street". Women wore hats on more formal occasions, but not too often as everyday wear. However, the headscarf was common, though like the men's hats it was in decline. Children wore the hats that their parents told them to wear: caps and balaclavas were common for boys, and bonnets for small girls. However, once the 1960s appeared few self-respecting teenagers wore anything on their heads except their flowing locks that grew in length as the decade progressed.

Consequently, for someone of my age it has been interesting to see which hats continued through the period of relative drought that the 1960s heralded, and how hats then made a comeback to the point where many teenagers have lost the habit of removing it when going indoors. Older men have always favoured hats, especially if their hair disappeared or thinned to the point where the summer sun would burn the top of their head. So, Panama hats never disappeared, and in Britain remained as sure a sign of summer as the thwack of leather on willow (cricket for the unenlightened) or the unveiling of tattoos on the midriffs of young women. But it's the rise of the American-style baseball cap that is the real surprise for me, given that baseball has about as much exposure in Britain as cricket has in the U.S. However, I suppose that these caps have been adopted world-wide as both headwear and a medium of advertising, so it's probably inevitable that they should fetch up on our shores too.

The other week I attended the Steam Threshing weekend at Bicker in Lincolnshire. This event, a small country fair that raises funds for the local church, features a variety of attractions but especially traction engines and an old-style threshing machine. As I made my first circuit of the field looking for photographs I came upon this group of men sitting on straw bales watching a traction engine. They were wearing a fine collection of hats - two Panamas, a baseball cap and a fisherman's hat (also, I believe, called a bucket hat, a "beanie"). They seemed perfect for one of my rare forays into people photography. Incidentally, I went to this event a few years ago and photographed a quite different collection of hats - see here.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 271mm

F No: f6.3

Shutter Speed: 1/1260 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

It's not only fashions in hats that come and go, hats themselves fall in and out of favour. When I was a callow youth the trilby and other styles of men's hats with brims were on the way out. Flat caps were following a similar course to near extinction, being favoured by older folk only. One hat that was worn by a few men, and which is rarely seen as daily wear now, was the beret. Some men had got into the habit of wearing one during the war, and continued (without the badge) when they returned to "civvy street". Women wore hats on more formal occasions, but not too often as everyday wear. However, the headscarf was common, though like the men's hats it was in decline. Children wore the hats that their parents told them to wear: caps and balaclavas were common for boys, and bonnets for small girls. However, once the 1960s appeared few self-respecting teenagers wore anything on their heads except their flowing locks that grew in length as the decade progressed.

Consequently, for someone of my age it has been interesting to see which hats continued through the period of relative drought that the 1960s heralded, and how hats then made a comeback to the point where many teenagers have lost the habit of removing it when going indoors. Older men have always favoured hats, especially if their hair disappeared or thinned to the point where the summer sun would burn the top of their head. So, Panama hats never disappeared, and in Britain remained as sure a sign of summer as the thwack of leather on willow (cricket for the unenlightened) or the unveiling of tattoos on the midriffs of young women. But it's the rise of the American-style baseball cap that is the real surprise for me, given that baseball has about as much exposure in Britain as cricket has in the U.S. However, I suppose that these caps have been adopted world-wide as both headwear and a medium of advertising, so it's probably inevitable that they should fetch up on our shores too.

The other week I attended the Steam Threshing weekend at Bicker in Lincolnshire. This event, a small country fair that raises funds for the local church, features a variety of attractions but especially traction engines and an old-style threshing machine. As I made my first circuit of the field looking for photographs I came upon this group of men sitting on straw bales watching a traction engine. They were wearing a fine collection of hats - two Panamas, a baseball cap and a fisherman's hat (also, I believe, called a bucket hat, a "beanie"). They seemed perfect for one of my rare forays into people photography. Incidentally, I went to this event a few years ago and photographed a quite different collection of hats - see here.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 271mm

F No: f6.3

Shutter Speed: 1/1260 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, September 14, 2012

Navigation Warehouse, Austen Fen, Lincolnshire

click photo to enlarge

Recently, as I crossed Austen Fen in North Lincolnshire, my attention was drawn to a building next to the road ahead. It was clear from the utilitarian grid of windows, centrally placed loading doors under a gable with the remains of a hoist arm, as well as the two louvred dormers on the roof, that it was an old warehouse. As I crossed a bridge over the adjacent Louth Canal and pulled over to the side of the road to take a photograph the question in my mind was, "How old is it?" I didn't have the opportunity to stop and examine the building in any detail, but my feeling was that it probably dated from the late eighteenth century or early nineteenth century. A little research at home proved inconclusive. A book about the industrial buildings and structures of the area calls it "late C18"; the official listing information that accompanies its Grade II status says "mid C19".

The Louth Navigation (i.e. canal) opened in 1767 so the late C18 is possible. A couple of details in my photographs that might push the date later are the slate roof (though this could be a replacement of a pantile roof) and the triangular heads on the window openings (segmental openings would be more likely on an earlier building). The next time I'm passing that way I'll try to stop for longer and have a more leisurely look at the structure. Whatever date it was built there was no doubt that it looked a fine sight in the low evening sun. I took some photographs of the canal with the building beyond and the main one of the facade reflected in the deep blue of the water with the thick reeds offering a framing of sorts.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Lumix LX3

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 12.8mm (60mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f2.8

Shutter Speed: 1/160

ISO: 80

Exposure Compensation: -0.66 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Recently, as I crossed Austen Fen in North Lincolnshire, my attention was drawn to a building next to the road ahead. It was clear from the utilitarian grid of windows, centrally placed loading doors under a gable with the remains of a hoist arm, as well as the two louvred dormers on the roof, that it was an old warehouse. As I crossed a bridge over the adjacent Louth Canal and pulled over to the side of the road to take a photograph the question in my mind was, "How old is it?" I didn't have the opportunity to stop and examine the building in any detail, but my feeling was that it probably dated from the late eighteenth century or early nineteenth century. A little research at home proved inconclusive. A book about the industrial buildings and structures of the area calls it "late C18"; the official listing information that accompanies its Grade II status says "mid C19".

The Louth Navigation (i.e. canal) opened in 1767 so the late C18 is possible. A couple of details in my photographs that might push the date later are the slate roof (though this could be a replacement of a pantile roof) and the triangular heads on the window openings (segmental openings would be more likely on an earlier building). The next time I'm passing that way I'll try to stop for longer and have a more leisurely look at the structure. Whatever date it was built there was no doubt that it looked a fine sight in the low evening sun. I took some photographs of the canal with the building beyond and the main one of the facade reflected in the deep blue of the water with the thick reeds offering a framing of sorts.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Photo 1

Camera: Lumix LX3

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 12.8mm (60mm/35mm equiv.)

F No: f2.8

Shutter Speed: 1/160

ISO: 80

Exposure Compensation: -0.66 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Wednesday, September 12, 2012

Abstraction and the Pre-Raphaelites

click photo to enlarge

click photo to enlargeAn exhibition of the work of the Pre-Raphaelite painters has recently opened at Tate Britain. It seeks to show the artists, in the words of The Guardian newspaper's arts correspondent, as "Britain's first modern art movement with rebellious ideas and revolutionary methods way ahead of their time." It seems to me that every few decades the Pre-Raphaelites are re-discovered, re-interpreted and presented anew to a public who have always been aware of them to a greater or lesser degree. And with each fresh look a different aspect of their achievement is highlighted. I've been to exhibitions that stress their medievalising, the way they were all-embracing (producing craft and literature as well as fine art), and that concentrated on their depiction of nature

It was the latter thread that came to mind when I reviewed my photographs of the surface of the River Witham where it runs through the Lincolnshire town of Grantham. Like many slow moving, lowland rivers,the Witham has a lot of weed growing in its main course. The long strands writhe in the flow, either as single strands or as bunches of aquatic tresses. The banks have lush grasses and reeds with overhanging trees casting dappled shade - willow, alder, black poplar and more. In places one is transported to the scene of Millais' depiction of the drowning Ophelia. The artist's eye lovingly shows the flowers, waterside plants and aquatic weeds of the Hogsmill River, a tributary of the River Thames, and one can easily get lost in the natural detail that his brush lingered over.

However, in my photograph of the River Witham I wasn't looking for a literal interpretation of the scene so much as trying to create a semi-abstract image that treats the reflections and weeds as lines, patches of colour and contrasting tones. It's an approach that in painting had to wait for Impressionism and later art movements though the seeds for the style were sown by the likes of Turner, Cotman and others. One of the things I like about photography is the way the camera can be used as a device to show the world in a literal way but can also represent it with an element of abstraction. It's a while since I've done a shot like this, so when I saw this interesting piece of water and weed below some overhanging trees my camera went straight to my eye.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 238mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/250 sec

ISO: 1600

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Monday, September 10, 2012

"Good bad" books and styling

click photo to enlarge

In his "Tribune" essay of 1945, "Good Bad Books", George Orwell argued for the existence of a type of book "that has no literary pretensions but which remains readable when more serious productions have perished." He borrowed the idea and title from G. K. Chesterton and applied it to authors that today are all but forgotten, people such as Leonard Merrick, Ernest Raymond and May Sinclair, but also to some who are still read and more widely recognised: E. Nesbit, Conan Doyle, Rider Haggard and others. His essential point was that "good bad books" are works that don't aim high but do score in terms of entertainment, effective and affective writing, and incidental insight. Moreover, he opined, they would be read long after the likes of Wyndham Lewis were forgotten, and cites in support of his case the enduring appeal of the less serious Anthony Trollope, over the more weighty but unreadable Thomas Carlyle.

The notion that something "bad" can be "good" has been applied in areas beyond books. For example, early British Pop Art practitioners such as Richard Hamilton and Peter Blake drew inspiration from the vigour and vitality of commercial graphics, posters, the circus and other "low" art, seeing in them qualities that they admired. In mainstream popular music there are a small number of artistes who rise above their medium and are liked, within their limitations, by people who generally wouldn't give the genre the time of day. I wouldn't dare to suggest examples!

I've often felt that manufacturers sometimes produce examples of car styling that have this "good bad" quality. In 2006 I posted a photograph of a Cadillac's fin and tail light cluster saying, "It's the sort of styling that you think should never have happened, but part of you is glad that it did." Today's photograph shows the front of the bonnet of a 1936 Ford V8 Coupe. The radiator mascot is a greyhound in the act of leaping over an 8 nestled in a V. This chromed device must be some kind of bonnet release. When I first saw it I immediately thought of what the protrusion might do to a pedestrian unfortunate enough to be struck by it. As I considered it further the ludicrousness of this piece of bad sculpture sitting on the bonnet like a canine parody of a Cellini salt-cellar struck me. And yet, all that notwithstanding, I felt a touch of admiration for the person who had crafted his (or her) artistic vision and persuaded Ford that it should adorn hundreds of thousands of their cars. Perhaps it was the way the chrome and the black bonnet were picking up the tinted late afternoon light that filtered through the clouds. Maybe I was just feeling more charitably inclined than usual towards what I consider bad design. Whatever the reason, I took the photograph and I'm glad that I did.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 105mm

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/250 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

In his "Tribune" essay of 1945, "Good Bad Books", George Orwell argued for the existence of a type of book "that has no literary pretensions but which remains readable when more serious productions have perished." He borrowed the idea and title from G. K. Chesterton and applied it to authors that today are all but forgotten, people such as Leonard Merrick, Ernest Raymond and May Sinclair, but also to some who are still read and more widely recognised: E. Nesbit, Conan Doyle, Rider Haggard and others. His essential point was that "good bad books" are works that don't aim high but do score in terms of entertainment, effective and affective writing, and incidental insight. Moreover, he opined, they would be read long after the likes of Wyndham Lewis were forgotten, and cites in support of his case the enduring appeal of the less serious Anthony Trollope, over the more weighty but unreadable Thomas Carlyle.

The notion that something "bad" can be "good" has been applied in areas beyond books. For example, early British Pop Art practitioners such as Richard Hamilton and Peter Blake drew inspiration from the vigour and vitality of commercial graphics, posters, the circus and other "low" art, seeing in them qualities that they admired. In mainstream popular music there are a small number of artistes who rise above their medium and are liked, within their limitations, by people who generally wouldn't give the genre the time of day. I wouldn't dare to suggest examples!

I've often felt that manufacturers sometimes produce examples of car styling that have this "good bad" quality. In 2006 I posted a photograph of a Cadillac's fin and tail light cluster saying, "It's the sort of styling that you think should never have happened, but part of you is glad that it did." Today's photograph shows the front of the bonnet of a 1936 Ford V8 Coupe. The radiator mascot is a greyhound in the act of leaping over an 8 nestled in a V. This chromed device must be some kind of bonnet release. When I first saw it I immediately thought of what the protrusion might do to a pedestrian unfortunate enough to be struck by it. As I considered it further the ludicrousness of this piece of bad sculpture sitting on the bonnet like a canine parody of a Cellini salt-cellar struck me. And yet, all that notwithstanding, I felt a touch of admiration for the person who had crafted his (or her) artistic vision and persuaded Ford that it should adorn hundreds of thousands of their cars. Perhaps it was the way the chrome and the black bonnet were picking up the tinted late afternoon light that filtered through the clouds. Maybe I was just feeling more charitably inclined than usual towards what I consider bad design. Whatever the reason, I took the photograph and I'm glad that I did.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 105mm

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/250 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Saturday, September 08, 2012

Anno, Wally and scrap metal

click photo to enlarge

When my children were small one of the books they enjoyed was "Anno's Journey"(1977) by the Japanese author and illustrator, Mitsumasa Anno. This was one of a series that chronicled the journey of a character through various landscapes and countries. "Anno's Britain" and "Anno's USA" were two further titles that I recall they liked. The charm of these books lay in the fascinating detail of the drawing. There were no words, just full page illustrations from which the child could invent their own narrative based on the activities (some very humorous) that they noticed. They were books to return to often, and which had appeal for a relatively wide age range. Studying the detailed drawings was the underpinning attraction of these books. This was something taken up by the British illustrator, Martin Hanford, in his "Where's Wally" ("Where's Waldo" in the U.S.) series. Hanford added the twist that Wally was difficult to find on each page, and whilst the first aim was invariably to find Wally, after that task had been completed the rest of the page could be scoured for all that it held. Children took to these books as much as they did to Anno's - perhaps more.

On a recent visit to Newark in Nottinghamshire I took a photograph from a bridge of the local metal scrap yard. It was a hive of noise and activity as workers, grab cranes, delivery and collection drivers busied themselves with the process of turning waste metal into a form suitable for transport and recycling. My long lens compressed the scene making it look more of a disorganised jumble than I imagine it is. Moreover, when I looked at the shot I noticed more people than I'd seen when I pressed the shutter. I set about counting how many there were, and immediately remembered Anno and Wally! Such is the way that the human mind - OK, my mind - works!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 97mm

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/200

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

When my children were small one of the books they enjoyed was "Anno's Journey"(1977) by the Japanese author and illustrator, Mitsumasa Anno. This was one of a series that chronicled the journey of a character through various landscapes and countries. "Anno's Britain" and "Anno's USA" were two further titles that I recall they liked. The charm of these books lay in the fascinating detail of the drawing. There were no words, just full page illustrations from which the child could invent their own narrative based on the activities (some very humorous) that they noticed. They were books to return to often, and which had appeal for a relatively wide age range. Studying the detailed drawings was the underpinning attraction of these books. This was something taken up by the British illustrator, Martin Hanford, in his "Where's Wally" ("Where's Waldo" in the U.S.) series. Hanford added the twist that Wally was difficult to find on each page, and whilst the first aim was invariably to find Wally, after that task had been completed the rest of the page could be scoured for all that it held. Children took to these books as much as they did to Anno's - perhaps more.

On a recent visit to Newark in Nottinghamshire I took a photograph from a bridge of the local metal scrap yard. It was a hive of noise and activity as workers, grab cranes, delivery and collection drivers busied themselves with the process of turning waste metal into a form suitable for transport and recycling. My long lens compressed the scene making it look more of a disorganised jumble than I imagine it is. Moreover, when I looked at the shot I noticed more people than I'd seen when I pressed the shutter. I set about counting how many there were, and immediately remembered Anno and Wally! Such is the way that the human mind - OK, my mind - works!

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 97mm

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/200

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.67 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Friday, September 07, 2012

Renegades, Warriors and Barbarians

click photo to enlarge

We all have our failures in life; some great and others small. One of my relatively small failures was buying a car. Anyone who has read this blog with any sort of regularity may recall that for a long time I tried to stick with public transport and the bicycle, but I eventually succumbed to four wheels following the birth of our second child and a couple of "difficult" experiences on the railways as Margaret Thatcher's government starved them of resources in the run-up to privatisation. However, despite my ownership of a modest vehicle I still believe, to adapt George Orwell's words in his novel, Animal Farm, "two wheels good, four wheels bad", and I still much prefer riding to driving.

I also retain fairly forthright views on cars and people's attitudes to them. For example, I consider sports cars and 4X4s to be anti-social vehicles. However, I also find a lot of humour in all vehicles powered by the infernal combustion engine. For instance, over the years I've watched with interest the increasing popularity of the four-seater pickup. You know the sort of thing - its a mixture of a car, 4X4 and old-style pickup van. I've also looked on with amazement as they've got bigger and bigger. But the thing about these vehicles that has most grabbed my attention is the silly names with which the manufacturers adorn them. In fact, I've been so fascinated by these that I keep a mental list of them that I try to update when a new example appears. So far I've recorded Renegade, Warrior, Wrangler, Outlaw, Animal, Gladiator, Trojan, Barbarian and Rodeo. There are probably more that I've forgotten, and I know that ever more ludicrous examples will appear (I suggest Vandal and Visigoth). Now I'm sure that there is a small group of people for whom such vehicles are entirely appropriate. But I'm equally sure that there's a large group of people (mainly but not exclusively men) for whom the size, the macho appearance, the "just in case" utility, and yes, those silly names, make them objects of great desire. Why have a bog-standard hatchback or saloon when you can be a rugged outlaw of the road that causes lesser vehicles to scatter at the very sight of your entirely superfluous bull-bars?

On a return journey from one of my regular but brief visits north of the River Humber we stopped off at the bridge that links Yorkshire with Lincolnshire. We trekked out to the middle of the enormous span and took in the view down to the city of Hull and upstream towards South Ferriby, Winteringham and beyond. As the traffic flashed by I took a few shots of the suspension cable anchors, looking to contrast the blurred vehicles with the sharpness of the bridge's structure. The best of the shots was this one with, yes, an over-sized pickup with a rear take-off cover and bright yellow ladders strapped to the top.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 24mm

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/160

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

We all have our failures in life; some great and others small. One of my relatively small failures was buying a car. Anyone who has read this blog with any sort of regularity may recall that for a long time I tried to stick with public transport and the bicycle, but I eventually succumbed to four wheels following the birth of our second child and a couple of "difficult" experiences on the railways as Margaret Thatcher's government starved them of resources in the run-up to privatisation. However, despite my ownership of a modest vehicle I still believe, to adapt George Orwell's words in his novel, Animal Farm, "two wheels good, four wheels bad", and I still much prefer riding to driving.

I also retain fairly forthright views on cars and people's attitudes to them. For example, I consider sports cars and 4X4s to be anti-social vehicles. However, I also find a lot of humour in all vehicles powered by the infernal combustion engine. For instance, over the years I've watched with interest the increasing popularity of the four-seater pickup. You know the sort of thing - its a mixture of a car, 4X4 and old-style pickup van. I've also looked on with amazement as they've got bigger and bigger. But the thing about these vehicles that has most grabbed my attention is the silly names with which the manufacturers adorn them. In fact, I've been so fascinated by these that I keep a mental list of them that I try to update when a new example appears. So far I've recorded Renegade, Warrior, Wrangler, Outlaw, Animal, Gladiator, Trojan, Barbarian and Rodeo. There are probably more that I've forgotten, and I know that ever more ludicrous examples will appear (I suggest Vandal and Visigoth). Now I'm sure that there is a small group of people for whom such vehicles are entirely appropriate. But I'm equally sure that there's a large group of people (mainly but not exclusively men) for whom the size, the macho appearance, the "just in case" utility, and yes, those silly names, make them objects of great desire. Why have a bog-standard hatchback or saloon when you can be a rugged outlaw of the road that causes lesser vehicles to scatter at the very sight of your entirely superfluous bull-bars?

On a return journey from one of my regular but brief visits north of the River Humber we stopped off at the bridge that links Yorkshire with Lincolnshire. We trekked out to the middle of the enormous span and took in the view down to the city of Hull and upstream towards South Ferriby, Winteringham and beyond. As the traffic flashed by I took a few shots of the suspension cable anchors, looking to contrast the blurred vehicles with the sharpness of the bridge's structure. The best of the shots was this one with, yes, an over-sized pickup with a rear take-off cover and bright yellow ladders strapped to the top.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 24mm

F No: f8

Shutter Speed: 1/160

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Thursday, September 06, 2012

One greenbottle is more than enough

click photo to enlarge

Some of the world's worst songs are not the output of say, the Spice Girls, Abba, or Justin Bieber* but are those that we teach to young children. The effect on me of songs such as "Michael Row the Boat Ashore", "Kumbaya", "Five Little Speckled Frogs" and "Ten Green Bottles" has been so profound that hearing one of these ditties today re-kindles in me thoughts of preceptorcide**. I know that many children enjoy the repetition, jollity, generally upbeat mood, or even the sentimentality of these songs. The trouble is that, as a foundation on which to build a deeper appreciation of music, they are jerry-built constructions, and may well account for some of the debased preferences of the music-buying public as evinced by what passes for the Top Forty today.

My annual sighting of a greenbottle fly triggered the words of the irritating song about ten green glass bottles mentioned above and the subsequent reflection on children's songs. As usual, I came across the colourful creature as I did a late summer tour of the garden in search of an image or two of the perennials that are now in full flower. When I first became acquainted with this fly I discovered that it has an unwholesome lifestyle and habits very much at odds with its incandescent appearance. Consequently I found it entirely appropriate that its name reminds me of one of the world's worst songs.

* On second thoughts the output of these"artistes" are among the world's worst songs.

** Preceptorcide: a word invented by me for this blog post. Work it out.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 100mm macro

F No: f5

Shutter Speed: 1/160 sec

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: 0 EV

Image Stabilisation: On

Some of the world's worst songs are not the output of say, the Spice Girls, Abba, or Justin Bieber* but are those that we teach to young children. The effect on me of songs such as "Michael Row the Boat Ashore", "Kumbaya", "Five Little Speckled Frogs" and "Ten Green Bottles" has been so profound that hearing one of these ditties today re-kindles in me thoughts of preceptorcide**. I know that many children enjoy the repetition, jollity, generally upbeat mood, or even the sentimentality of these songs. The trouble is that, as a foundation on which to build a deeper appreciation of music, they are jerry-built constructions, and may well account for some of the debased preferences of the music-buying public as evinced by what passes for the Top Forty today.

My annual sighting of a greenbottle fly triggered the words of the irritating song about ten green glass bottles mentioned above and the subsequent reflection on children's songs. As usual, I came across the colourful creature as I did a late summer tour of the garden in search of an image or two of the perennials that are now in full flower. When I first became acquainted with this fly I discovered that it has an unwholesome lifestyle and habits very much at odds with its incandescent appearance. Consequently I found it entirely appropriate that its name reminds me of one of the world's worst songs.

* On second thoughts the output of these"artistes" are among the world's worst songs.

** Preceptorcide: a word invented by me for this blog post. Work it out.

photograph and text © Tony Boughen

Camera: Canon