click photo to enlarge

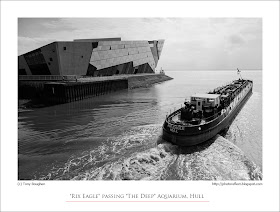

Photographic composition can be approached in a number of ways. One that I like, and which I don't use enough since I moved to a rural location - is juxtaposition, the conscious placing of disparate objects in the frame.This technique is one that comes easily to painters, but is slightly more difficult for photographers. Firstly the juxtaposition has to be seen, then it has to be organised into a composition. Often this will mean excluding objects and the photographer changing position to bring the juxtaposed objects into "engagement". It is a device that can work well where the objects are figurative, but also where the intention is to construct an image with semi-abstract elements.

The other day, when walking near "The Deep" aquarium in Kingston upon Hull, I noticed a building that I'd seen before but had never looked at. It is a blocky structure, clearly utliitarian, probably connected with its futuristic looking neighbour, and has a mosaic-like decoration on its main facade. It wasn't just the building that caught my eye, however, but the building and the car park arrow on the tarmac in front of me. I framed my shot so that the ranks of parked vehicles to left and right were excluded, and let the juxtaposition of the arrow, the horizontal bands and the colourful grid work together in my composition.

photograph and text (c) T. Boughen

Camera: Canon

Mode: Aperture Priority

Focal Length: 65mm

F No: f7.1

Shutter Speed: 1/640

ISO: 100

Exposure Compensation: -0.33 EV

Image Stabilisation: On